In my research into the relationship between women and cars, I often come across unique and interesting woman-car stories. I recently read an article in Automobile Magazine about Belinda Clontz – a California female car enthusiast with a particular fascination for Mercedes-Benz. While I expected her passion to be inspired by the luxury car’s prestige, classic style, and noteworthy performance attributes, I was surprised to discover that it was a woman’s contribution to the development and introduction of the automobile that garnered her attention and devotion. As noted by Clontz – the proud owner of a 1962 Mercedes Benz 220S Fintail – it was Bertha Benz, the wife of inventor Karl Benz, who introduced the original Benz Patent-Motorwagen to the world. In 1888, with her two children in the back seat, Bertha embarked on a 65-mile trip and in the process, made history as the first person – of either sex – to drive a car such a long distance. As Clontz remarks, “I admire any woman who is willing to do something that no one else has done. Bertha Benz was ahead of her time and I consider her a significant pioneer in the creation of the automobile.”

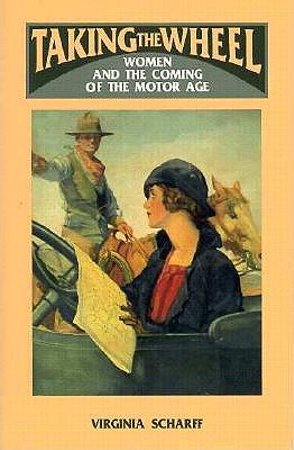

In the mid 1970s, feminist historians embarked on a movement to “write women into history.” These groundbreaking individuals challenged earlier traditions of intellectual and cultural history to consider whether historians could learn from other subjects – e.g. female – of study. Scholars began to think about not only about those reputed to have made history but also for those for whom historical events were backdrops to ordinary lives. Women’s history became one of the substantial new fields of study that emerged from this mid-twentieth century development.

It wasn’t until the late twentieth century that historians began to consider women’s influence within the field of automotive history. Scholars such as Virginia Scharff, Margaret Walsh, and Ruth Schwartz Cowan were instrumental in recovering the woman driver from the automotive archives. While Belinda Clontz is not a historian, she recognizes that women’s contributions to automotive history and culture are often overlooked. Her Facebook page is filled with homages to female Mercedes enthusiasts in particular and car lovers in general. She is encouraging to new auto aficionados, particularly young women with a passion for cars. In her posts she often reflects on what Mercedes ownership and being part of the Mercedes car culture has contributed to her identity and life.

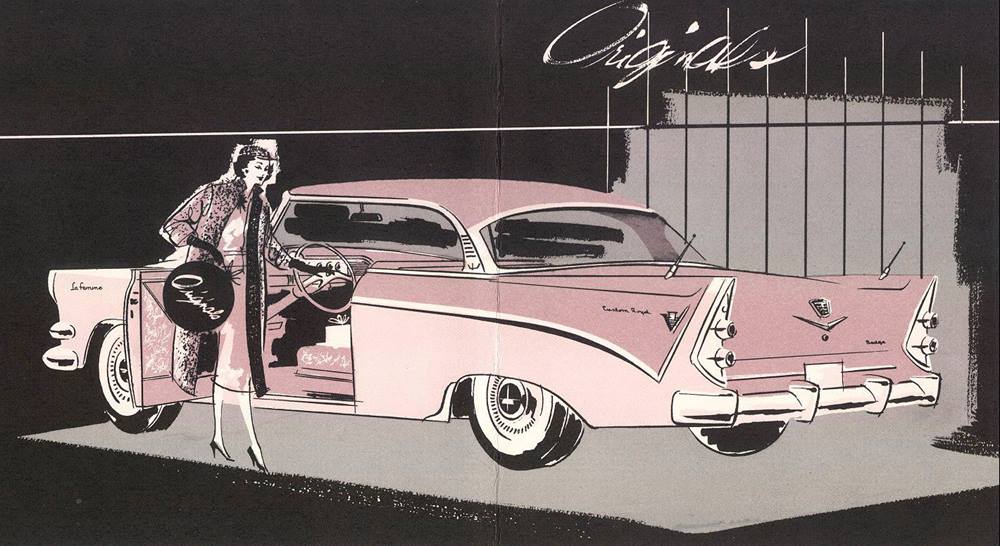

While Clontz’s purchase of the classic Mercedes was influenced by the role of Bertha Benz in its introduction and production, female influence was felt in other automotive arenas. In her research into the history of Fintails, Clontz found that Ewy Rosqvist and Ursula Wirth won the 1962 Grand Prix of Argentina in a Mercedes-Benz 220SE Fintail – the first women to ever do so. As Clontz confessed, this serendipitous discovery made ownership of the Fintail even more meaningful.

Although the automobile has a longstanding history as a primarily male interest, women today are discovering new and exciting ways to grow an interest in cars and take part in automotive culture. Although Clontz grew up with a fascination with automobiles, she found a special connection to the Mercedes due to its early – and heretofore unrecognized – female influence. As Clontz asserts, “My love for Mercedes-Benz stems from the fact that it was helped to be founded by a woman. Bertha Benz believed so much in her husband’s Motorwagen that she invested her inheritance money in his business. Although she was not allowed to be named as one of the inventors at the time, Bertha also contributed to the design and engineering of the Motorwagen. She took the Motorwagen on its first test drive and helped put Karl Benz on the map as the inventor of the first automobile. Her role in the history of Mercedes-Benz is influential and inspires me every time I get out on the road with my Fintail.”

Segura, Eleonor. “Meet the Gorgeous 1962 Mercedes-Benz 220S Fintail and Owner Belinda Clontz.” Automobilemag.com 14 Feb 2020.

Do you have an interesting car story? Please share it below.