As a longtime Volkswagen fan, I recently discovered a book on its history that garnered a little bit of positive attention when it was published in 2012. In Thinking Small, an “auto” biography of the Volkswagen Beetle, Andrea Hiott traces the trajectory of the famous auto from its conception as the “people’s car” in Nazi Germany to its emergence as an anti-establishment icon in 1960s America. While the book is ostensibly about the strange car, Hiott also focuses on the people who made it happen – Ferdinand Porsche, whose imaginings served as the inspiration for the Beetle’s eventual production, Heinrich Nordhoff, the German Industrialist who created the positive environment for its manufacture, and Bill Bernbach, whose advertising campaign created the American market for the little German car.

As Hiott notes, the Beetle, initially launched in 1938, was not an instant success. Although as an automobile it had little in common with the Model T, Nordoff, after taking the Volkswagen reins in 1947, adopted Henry Ford’s business philosophy to the struggling German car. In the introduction of the Model T, Ford’s objective was to manufacture an affordable car for “everyman”; the tycoon’s famous “$5 a day” promise to automotive workers assured that the people who built the cars could also afford them. Under Nordhoff’s guidance at the Wolfsburg VW factory, workplace conditions improved and benefits to workers increased; consequently, the reliable and affordable Beetle grew increasingly popular with the masses, eventually becoming the “people’s car” that Porsche had originally imagined.

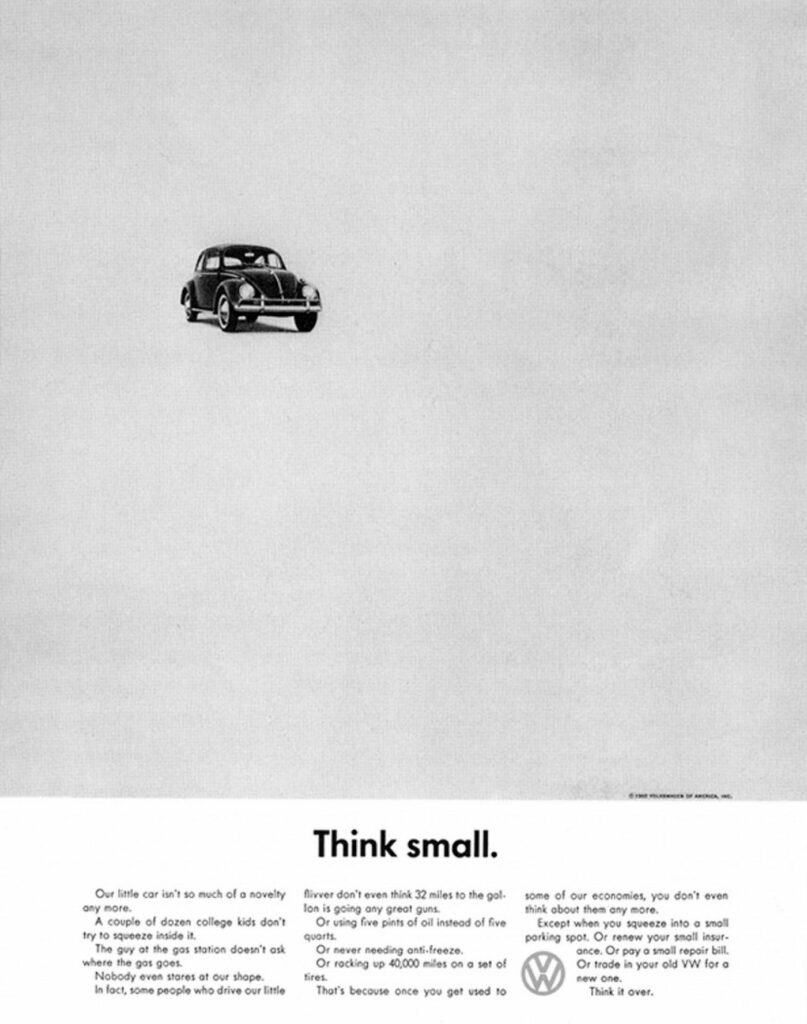

When the German car came to the United States, the funny-looking little car became the foil to the big, brash behemoths coming out of Detroit. The Bug was embraced by the counter culture; it became the car of choice for strapped-for-cash college students and members of the Woodstock generation. As one of those broke college kids, I purchased my own Beetle in 1970; it was one of dozens that could be found on Detroit’s Wayne State University commuter campus. Although I was hardly the anti-establishment type, as a Detroit native growing up in a community of autoworkers, the VW parked in my driveway no doubt marked me as a “traitor” in my neighbors’ eyes. However, as someone who aspired to work in advertising, VW’s marketing strategy, created by the advertising stars at Doyle Dane Bernbach, convinced me that I was driving the coolest car on the planet.

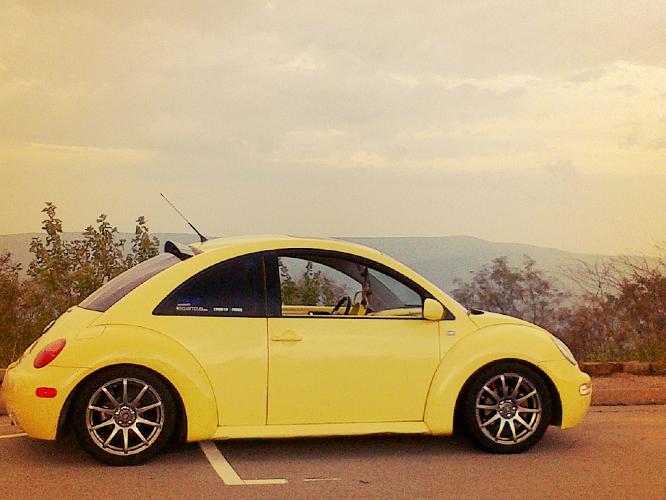

The last Beetle that evolved from Porsche’s original design, manufactured in Mexico, drove off the production line in 2003. However, affection for the funny little car never really died. In 1994, at the New American International Auto Show, the retro-inspired New Beetle concept car was unveiled. The production model arrived in 1997, “just in time to catch a wave of nostalgia and surf in all the way to sales success’’ (McAleer). The New Beetle was initially met with great enthusiasm and attained modest sales numbers. However, the retro version was not without controversy. Although, Hiott asserts, it was embraced by the hipster generation, descriptors such as “cute,” “playful,” and “fun” led to the New Beetle’s perception as a “chick car,” which was believed to turn off potential male buyers.

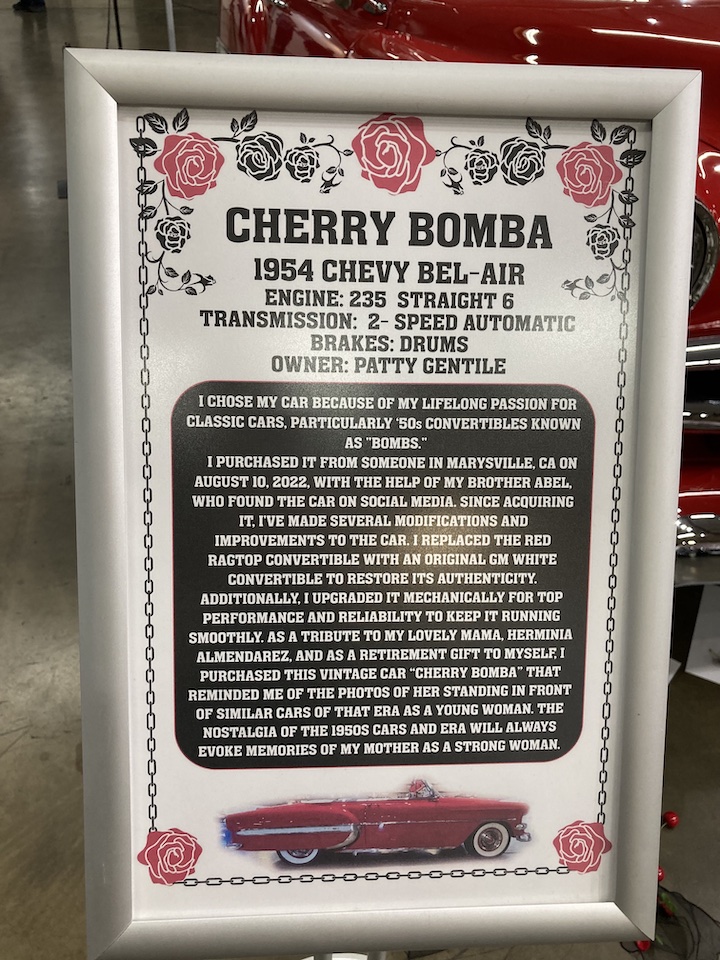

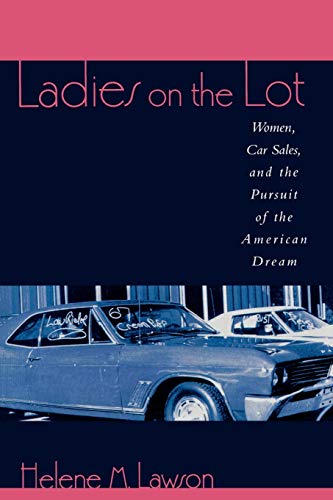

The chick car, as I defined in a 2012 article, is a small, sporty car designed for men but appropriated by women for their own use. They are affordable, quick, nimble, easy to handle, and most importantly, “fun to drive.” The chick car is the antithesis of the “woman’s car”, a sturdy and practical vehicle – i.e. station wagon, minivan, small SUV – used to transport kids and cargo. As I discovered, to the women who drive them the chick car represents personal freedom, independence, agency, and a sense of empowerment.

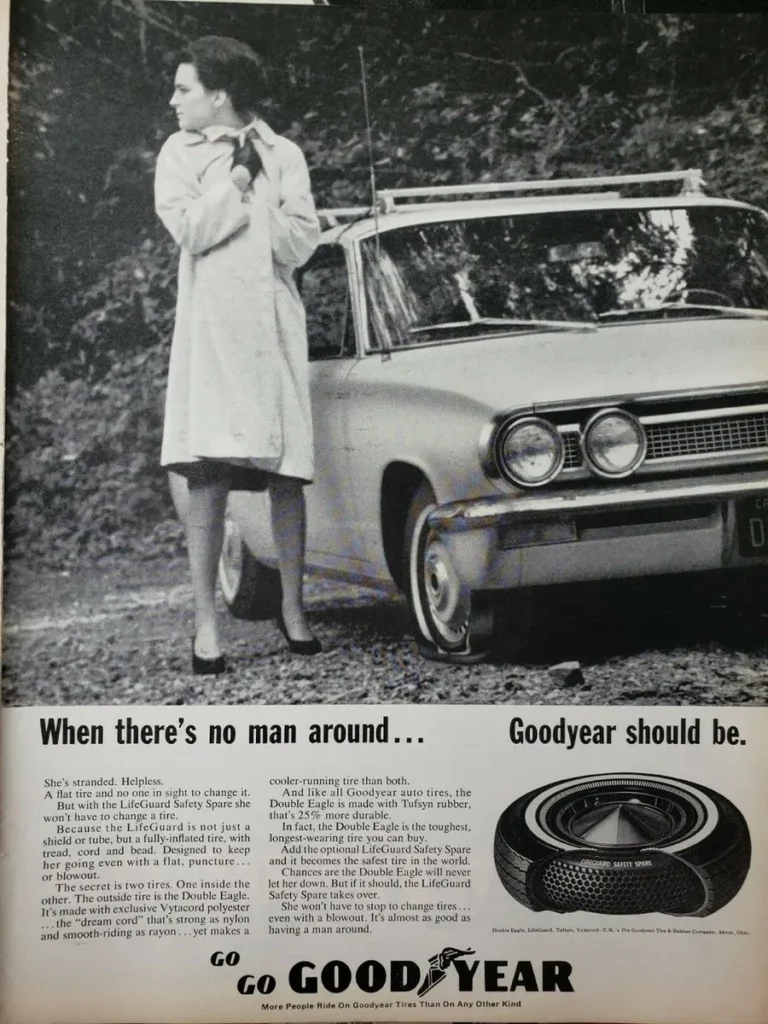

During the height of the chick car’s popularity, Terry Jackson of Bankrate.com wrote, “Carmakers recognize the powerful influence women have today in the auto marketplace while they simultaneously have to avoid sending a message to men that they shouldn’t be caught dead driving these cars.” While automakers welcome the female consumer, the “chick car” label creates a good amount of anxiety and concern among them. Car manufacturers are uneasy when automobiles become associated with femininity and the female car buyer.

Automakers responded to chick car dilemma in a number of interesting ways. Volkswagen “beefed up” the offending car to be more masculine. As auto writer Doron Levin wrote, “VW has attempted to ‘male up’ the New Beetle over the years by adding a turbocharger to the engine and a spoiler to the rear.” In 2012, VW introduced a “bigger, less ‘cute’, and sportier Beetle” in an attempt to ditch the “girl” car image and attract more male buyers (Healey).

Apparently the efforts to masculinize the little car were unsuccessful. As Anthony Capretto argues, “People weren’t able to move past this image, and these and other factors caused sales to drop substantially by the end of its life.” Whether or not the car’s downfall can be explained by its association with the woman driver seems an easy out as there are still plenty of “chick” cars – e.g. Mini Cooper, Miata – on the road in 2025. Regardless, in 2016, VW discontinued the nameplate after its nearly 80 years of existence.

Published in 2012, Thinking Small ends on an optimistic note. As Hiott wrote, “the car is still an object we want to love. Its story is still being written” (424). While the New Beetle is no longer being manufactured, it is has gained new appreciation among the collector set. As McAlleer exclaims, “More than a decade after the New Beetle left showrooms, it’s starting to become a choice for younger enthusiasts. […] because it’s such a whimsically adorable design, seeing a modified New Beetle can’t help but put a smile on your face.” Although Hiott couldn’t predict the car’s ending, she exhibited an astute understanding of the car’s effect on generations of drivers.

As a previous owner of two Beetles – 1970 and 1979 Super Beetle cabriolet – I have a strong affection for the odd little car. And after learning of the Bug’s early struggles to gain footing in post war Germany, its unlikely emergence as a cultural icon in the United States, and its stint as a popular albeit controversial chick car, I have a new appreciation for the Beetle’s history and its incredible sustainability over nearly 8 decades. Although this post comes over 10 years too late, I would recommend Thinking Small to anyone who has ever had a bit of a love affair with the Volkswagen Beetle.

Capretto, Anthony. “It’s Time We Gave the Volkswagen New Beetle the Respect it Deserves.” CarBuzz.com 19 Dec 2024.

Healey, James R. “2012 VW Beetle Gets Bigger, Ditches ‘Girls’ Car’Image.” USA Today. 10 Apr. 2011.

Hiott, Andrea. Thinking Small: The Long, Strange Trip of the Volkswagen Beetle. New York: Random House, 2012.

Jackson, Terry. “Top Five Chick Cars.” Bankrate.com. 1 Nov. 2007.

Levin, Doron. “Are You Man Enough to Drive a Chick Car?” Bloomberg News. 18 Apr. 2006.

Lezotte, Chris. “The Evolution of the ‘Chick Car’ Or: Which Came First, the Chick or the Car?” Journal of Popular Culture 45/3 2012.

McAleer, Brandon. “Volkswagen’s New Beetle is Finally Growing its Own Following.” Hagerty.com 24 Jan 2025.