Over the past year I have visited a dozen automotive museums. This journey was taken on not only due to my fascination with automobiles and car culture, but as part of a project examining the representation of women in institutions devoted to the automobile. As much of my research investigates women’s participation in car cultures associated with masculinity and the male driver, I thought auto museums would be an interesting location in which to observe how women – who compose over 50% of licensed drivers – were integrated into the automotive histories car museums represent. My first impressions were not encouraging. It was difficult to find evidence of women among the many aisles of automobiles owned, donated, driven, and produced by men. My original intention, therefore, was to focus primarily on the absences; to investigate the investigate the practices and processes that led to women’s invisibility in these masculine institutions. However, as I made my way through a dozen automotive museums, I noticed that women were, in fact, present, although not in the ways or in the places one might expect. I discovered evidence of women’s automotive participation hidden in dusty corners, tacked high up on walls, and in the back of smudgy glass cases. I found artefacts of women’s automotive history in unidentified photographs, yellowing news articles, and collected promotional materials. I thus came to the decision that rather than examine and question what was missing, to focus on what was there. I took the advice of historian and museum studies scholar Helen Knibb, who wisely wrote ‘collections, despite biases of gender, class, race, and creed, fragmentation, incompleteness, and regional disparities, can be an important primary source for the study and presentation of women’s history.’ Thus my objective became to uncover references to women’s automobility wherever I could find them, and in doing so construct a pieced-together, museum-inspired history of women and the automobile.

On first glance, women in auto museums appear only intermittently, primarily as mannequins in a passenger seat without any frame of reference. As historian Jennifer Clark notes, ‘we are not told anything about their journey, nor, for example, anything about the ideas of gender and class associated with driving and riding in vehicles.’ I found this to be true in many of the ‘collection’ museums I visited; female mannequins dressed in period costumes without any explanation or context appeared as an afterthought or ‘cursory’ addition to satisfy some sort of gender imperative. Yet other museums, those who adapted a social history approach or focused on a particular manufacturer or place, were more likely to include women in other ways. As I toured the museums, I discovered common themes in how women were represented. What follows, in this and subsequent blogs, are categories that provide insight into how women have made an impact in automotive history.

Exceptional women

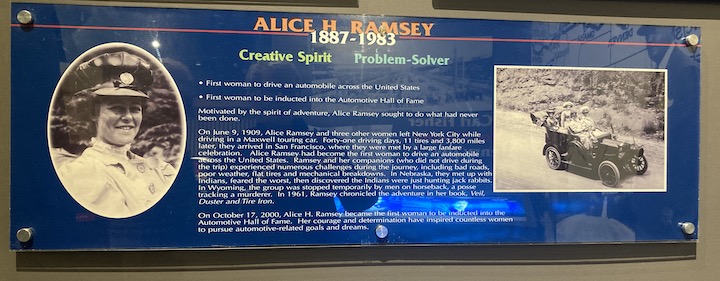

The exceptional woman is one who has made a name for herself in automotive history. This category includes women who are easily recognized outside of the automotive community as well as those, while less familiar, are highly regarded within it. Many of the women are noted for being ‘firsts’ in a culture and climate that is overwhelmingly male. Women who have achieved success and notoriety in motorsport make up the majority of these featured individuals. A few of the museums dedicate a considerable amount of space to these racing legends; exhibits focused on drivers such as Danica Patrick, Lyn St James, Janet Guthrie, and Sara Christian often incorporate photographs, artifacts, racing gear, and memorabilia. Some – including the Henry Ford and Automotive Hall of Fame – actually feature cars driven by the women – facsimiles or the real thing. Museums that focus on a particular geographical location will often refer to a familiar female figure in motorsport who was born or who had a significant win in the area. The Saratoga Automobile Museum, for example, stakes claim to drag racing legend Shirley ‘Cha Cha’ Muldowney, who got her start off the streets of Schenectady.

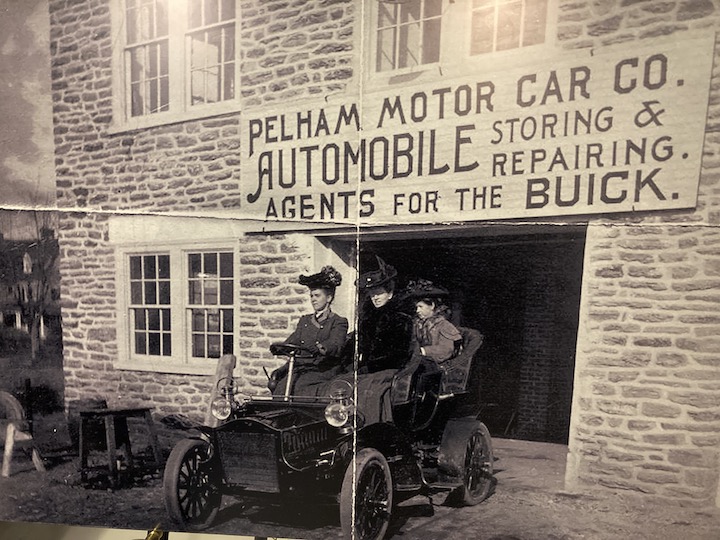

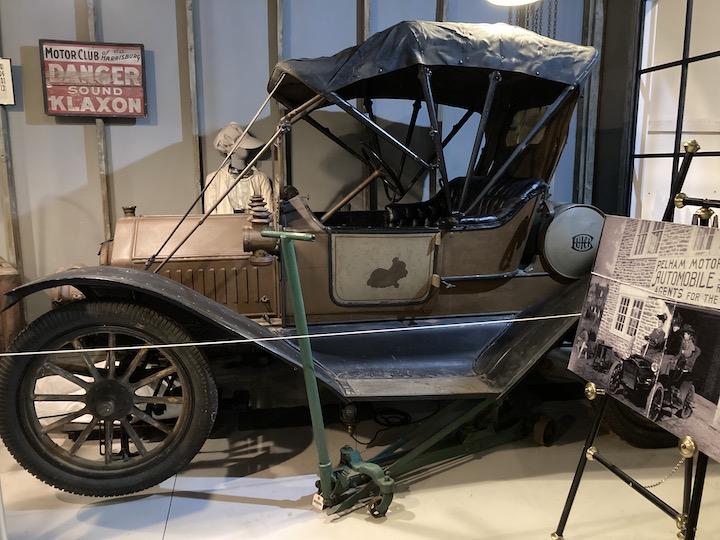

Early female automotive pioneers are also honored in a number of car museums. Attention is given to Alice Ramsey – the first woman to drive an automobile across the United States – as well as early-twentieth century rally driver Joan Newton Cuneo. However, often such references are hidden away and are only come upon by accident. Bertha Benz, the wife of automotive legend Karl Benz, was famous in her own right and is represented in a number of museums alongside an early Benz automobile. Investing her inheritance in Karl’s business, Bertha motored one of her husband’s automobiles from Mannheim to Pforzheim in 1888, drawing attention not only to the automotive manufacturer but to the tenacity and talent of women behind the wheel.

The exhibits featuring female pioneers in automotive history – whether taking up a significant amount of museum space or tucked away in a glass case – incorporate women as symbols of female success in male dominated fields and as important contributors to women’s automotive history. In doing so, such representations offer inspiration and aspiration to all – particularly female visitors – in attendance.

Famous women

Well-known women with a connection to automobiles are the subjects of exhibits in a number of automotive museums. Corporate institutions in particular often create displays that feature female film stars, celebrities, public figures, or dignitaries who have owned, driven, or been photographed with one of the manufacturer’s more celebrated models. One of the more popular individuals featured in a number of museums – and with a variety of cars – is Amelia Earhart. An acknowledged auto enthusiast known for her love of power and speed, Earhart is referenced in the Wisconsin Automotive Museum in association with the Kissel Speedster aka Gold Bug, which she drove across country in 1923. The Henry Ford, Ypsilanti Automotive Heritage Museum [YAHM], and Stahl’s Automotive Foundation Museum each draw attention -through photographs, publicity material, and similar automobiles – to Earhart’s christening of the 1933 Hudson Terraplane. The Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Museum [ACD] calls upon date of Earhart’s ill-fated attempt to circumnavigate the globe as a historical touchstone, allowing museum visitors to place a vehicle within a specific time and place. Other celebrities – including actresses Mary Astor and Anita King – are also celebrated for their love and promotion of fine automobiles. This connection between famous women and cars was perhaps one of the earliest examples of celebrity endorsement. Such publicity not only brought attention to the cars, but also suggested that women were capable of appreciating and handling automobiles for the style, notoriety, and freedom they provided.

These categories represent just two of the many groups of women I discovered on my automotive museum journey. As the number of categories – and representative women – grew, I gained a better understanding of the contributions women have made – large and small – to automotive history.

Clark, Jennifer. ‘Peopling the Public History of Motoring: Men, Machines, and Museums.’ Curator The Museum Journal Vol 56 Number 2, April 2013, 279-287.

Knibb, Helen. ‘Present but Not Visible’: Searching for Women’s History in Museum Collections.’ Gender & History Vol 6 No 3, November 1994, 352-369.