I am a native Detroiter, and have spent the majority of my life in car-centric southeastern Michigan. I grew up during the Golden Age of car culture, and spent part of my past life writing car commercials. Once I entered graduate school as a senior citizen, my motor city background and aging second wave feminism led me to the relationship between women and cars as a research focus. My subsequent projects have considered how women negotiate membership in historically masculine automotive spaces as well as how women’s connection to cars is represented in popular culture.

My current project centers on the representation of women in automotive museums. As a historically masculine space, I was interested in whether any effort had been made by automotive museums to integrate women into automotive history. As museums in general have slowly and often stubbornly moved toward a social history model, I was curious as to whether institutions devoted to the automobile had bought into the current museum trend or if they continued to reflect primarily male preferences and influence. As Jennifer Clark writes, ‘motor museums are conservative in style, with an influential – and overwhelmingly male dominated – collecting and visitor base’ (280). The answer to the either or question is, of course, is ‘yes’. Some museums have embraced the new direction while others have dragged their feet. Yet looking closely one can observe female influence and interaction with the automobile in most museum settings. As noted in previous blogs, female representation within the museum falls into categories which reflect women’s various roles in automobile culture. What follows are the three remaining themes I have developed in my observations of 12 automotive museums.

Consumers

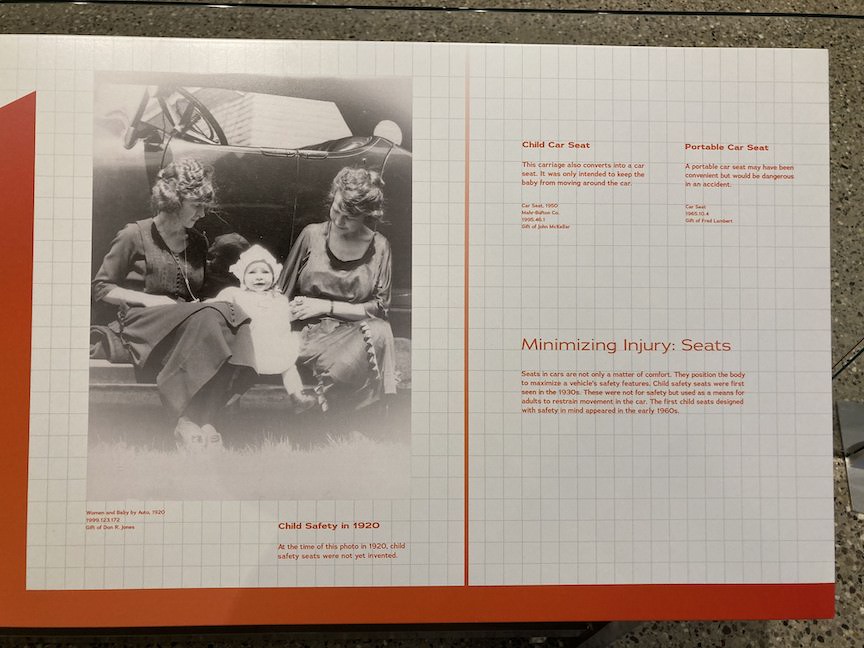

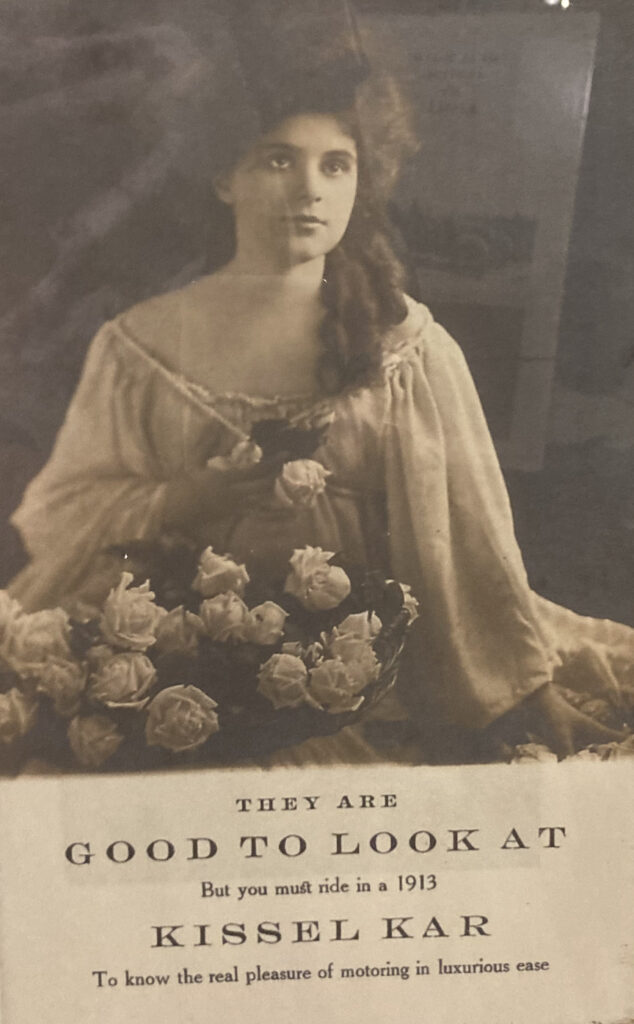

Women as consumers and drivers are presented in museums through photographs, advertisements, and the cars on display. Much attention is given to the connection between women and electric cars; electrics were advertised as appropriate for women for their cleanliness, quiet, and ease of operation. More than one museum mentions that Henry Ford purchased an electric for his wife Clara – whether Mrs Ford actually preferred the electric or it was acquired to keep her close to home is hard to say. However, the Piquette also features photographs of women driving the gasoline-powered Model T, which suggests women may, in fact, preferred the power and range such a vehicle provided. One of these photographs includes a caption that notes that, although women were routinely ignored by the auto industry, Ford recognized them as an important market for reliable, inexpensive cars.

Women’s role as consumer is most evident through the promotional materials displayed at almost every museum I visited. Exhibits at the Wisconsin museum, for example, include post war advertising which features women as Nash consumers, test driving automobiles, and speaking with car dealers. At the Henry Ford, which focuses on car culture rather than particular automobiles, women are very much present as consumers, drivers, workers, and influencers. They are introduced as early proponents of bicycles and the Model T as well as the minivan. They are represented in promotions about style, design, and safety. Women’s changing roles in advertising – as objects, symbols, moms, and adventurers are also addressed.

Agents

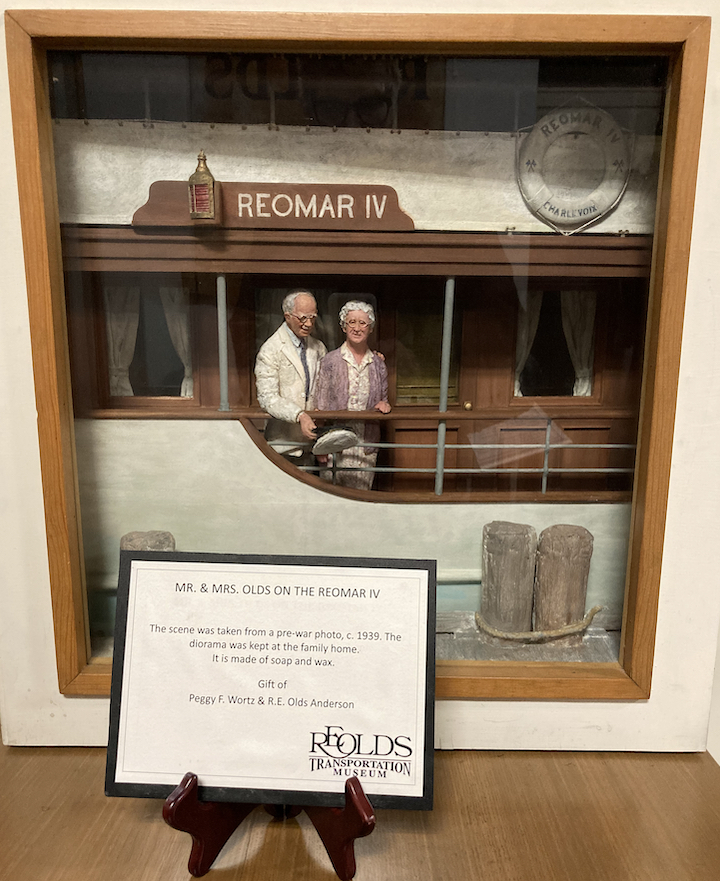

Women – as individuals who make things happen – was an understated but underlying theme in many of the automotive displays. Wives of industry innovators – including Clara Ford and Bertha Benz – were often silent but important partners and contributors to their spouses’ success. Clara Ford worked with her husband on what was to be known as the ‘Kitchen Sink Engine Model’ as she helped with its testing in the Ford family kitchen. Bertha Benz not only invested her inheritance in her husband’s business, but through her cross country trip, brought the Benz-Patent Motorwagen worldwide attention and got the company its first sales. The tour of the RE Olds Transportation Museum begins with a focus on the Olds family and homestead. Much of that is devoted to Metta Olds, the wife of the company founder. The artifacts on display – photos, family trees, furniture, personal items, clothing, and a book focused on the couple suggests that Metta was very much a silent partner and supporter of her husband and his business. While ‘the woman behind the man’ is somewhat of a cliché, the attention to wives of industry founders within multiple museums suggest they were significant contributors to early automotive history.

Women who served the automotive industry in other capacities were also acknowledged. The Sloan Museum recognizes women’s important role as members of the Emergency Brigade during the 1936 General Motors Sit-Down Strike. As noted in Jalopnik, a popular automotive site, ‘Many think of factory work, and therefore a strike in the automotive industry, as something primarily men would do. But it was the members of the Women’s Emergency Brigade, a paramilitary group of women inside the United Auto Workers union, who proved to be the secret weapon in that group’s triumph over General Motors.’

While not as prominent as the mostly male movers and shakers of the automotive industry, women on the sidelines often created important roles for themselves, as influencers and agents of change in the home, on the factory floor, and on the picket line.

Gatekeepers

Transportation museums often honor those responsible for the preservation, maintenance, and promotion of automotive history. Women have served in these roles; their contributions are found in glass cases, museum walls, and foundations and positions bearing their names. The Dunning Carriage to Cars Exhibit in the Sloan is funded by the Margaret Dunning Foundation. Dunning, known for her love of classic cars, established the foundation to nurture the preservation and teaching of automotive history for all Sloan visitors, but in particular for residents of the county in which the Sloan resides. The exhibit is an important component of the museum’s interactive History Gallery, which intertwines local automotive history with stories of Flint life, employment, neighborhoods, schools, housing, and tourism. Helen Earley, the First Lady of Oldsmobile, was a long time RE Olds Museum employee who created a position for herself as the resident Oldsmobile historian. As a scholar, historian, and archivist, Earley established the Oldsmobile History Center and co-authored two books on Oldsmobile history. The museum ‘board room’ bears her name and her likeness; further information is contained in a glass case hidden holding a few photos and a self-authored obituary.

Many of the museums I visited – Automotive Hall of Fame, Saratoga Automotive Museum, the Henry Ford, Wisconsin Automotive Museum, RE Olds Transportation Museum, Stahl’s Automotive Foundation Museum, to name a few – have installed women as directors, managers, trustees, and other decision-making positions. This is a hopeful sign that continued efforts will be made to incorporate and include the contributions of women – as drivers, consumers, workers, and influencers – into the annals of automotive history.

The categories provided here represent my initial observations on the representation of women in automotive museums; as I delve deeper I will certainly uncover more. What this examination has uncovered is not only that women are vastly underrepresented in these locations, but that women have, in fact, contributed to automotive history in varied and important ways. As Knibb writes, ‘the absence of women’s history from the permanent galleries of a museum does not necessarily mean that the museums’ collection is weak in objects relating to women’s lives.’

Automotive history has been long been documented as an account of powerful men and male machines. Because women’s relationship to the automobile differs from that of men, and because women are most likely to be judged against male achievements, women’s history with automobiles has been considered less legitimate; consequently, it is less likely to be recorded. As I hope to demonstrate in this project, automotive museums, as collections of objects and artifacts related to the motor car and its industries, provide an important, if not imperfect, resource for the recovering of women in automotive history.

Clark, Jennifer. ‘Peopling the Public History of Motoring: Men, Machines, and Museums.’ Curator The Museum Journal Vol 56 Number 2, April 2013, 279-287.

Knibb, Helen. ‘Present but Not Visible’: Searching for Women’s History in Museum Collections.’ Gender & History Vol 6 No 3, November 1994, 352-369.

Marquis, Erin. “‘Women That Would Gladly Give Their Life’: How The Paramilitary Women’s Emergency Brigade Battled GM At The UAW’s First Big Strike.” Jalopnik 9 Oct 2023