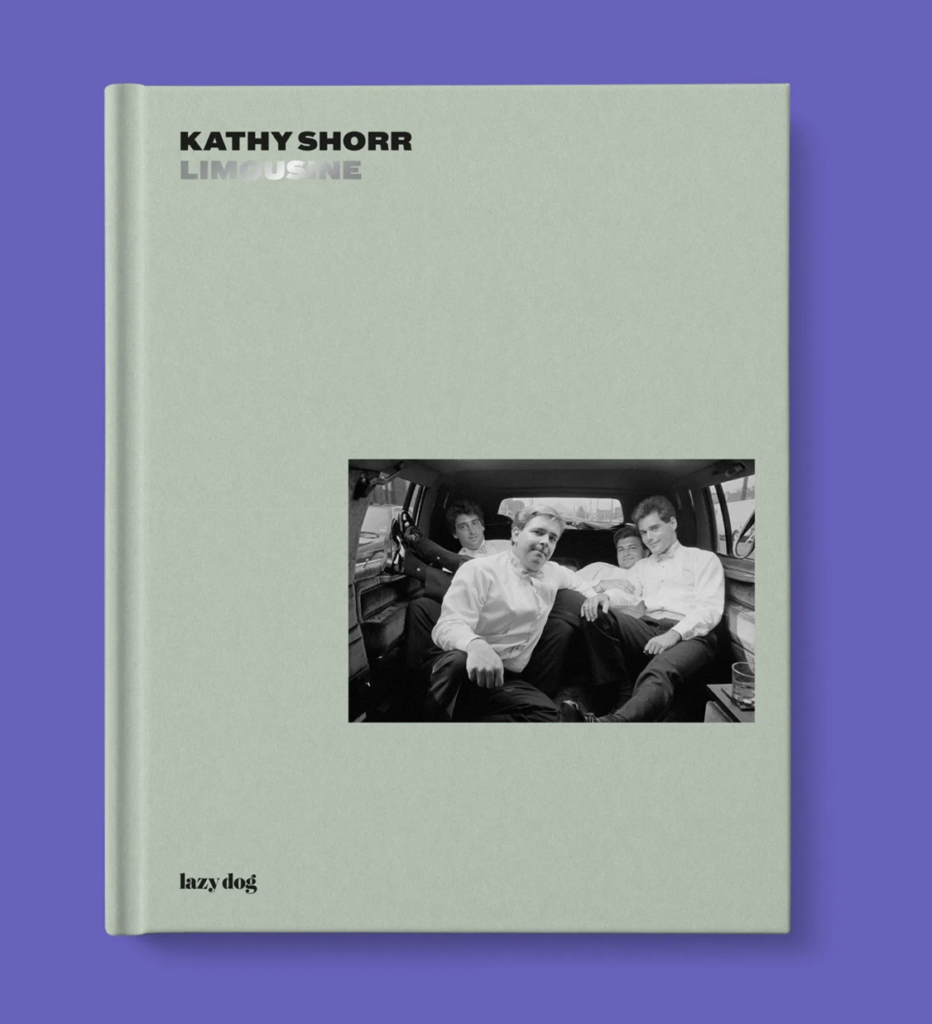

Participating in academic conferences is not only a great opportunity to present one’s work, but leads to encounters with other scholars with similar interests. While presenting at the Popular Culture Association National Conference a number of years ago, I was included on a panel with Katherine Parkin, a professor of social history at Monmouth University. Parkin had just published Women at the Wheel: A Century of Buying, Driving, and Fixing Cars, which went on to win the Emily Toth Award for best book in women’s studies and popular culture. Since we were both writing about women and cars, we had a lot to talk about. While my scholarship is primarily limited to that topic, as a historian Parkin writes on a variety of subjects; her research interests include the history of women and gender, sexuality, advertising, and consumerism. Parkin is often sought after to engage in various projects; however, as both a teacher and researcher she does not always have the time to accept all of the invitations. To my good fortune, Parkin has passed on some of those projects to me. These have included a book review, a chapter in a book on the history and politics of motorsports, and the most recent, an introduction to Limousine – a recently published book of award-winning photographs by Kathy Shorr.

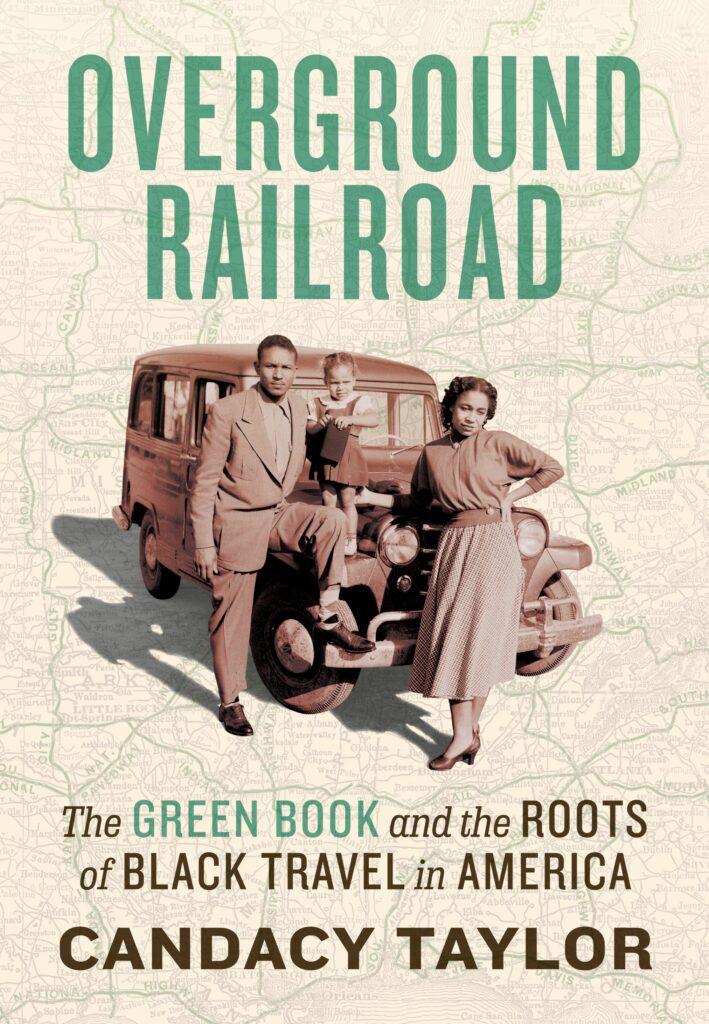

The photographs in Limousine were taken in 1988, shortly after Shorr graduated from the School of Visual Arts in New York. For this project, Shorr became a limo driver for nine months, working for the Crystal Limousine Company in Brooklyn. Unlike the majority of Brooklynites who did not possess driver’s licenses, eschewing the automobile in favor of public transportation, Shorr grew up a car girl; she purchased her first car – a Buick Skylark – while still a teen. Thus the decision to select a limo for this project came naturally to Shorr as it satisfied her love of driving while the vehicle served as a studio on wheels. As I write in the intro, “The limo’s posh interior served as a private space for personal conversations, boisterous drinking parties, and more than a few romantic interludes. While the limousine served a practical purpose, it also transmitted messages about those who rode in it. Shorr’s passengers called upon the limousine to construct new, albeit temporary, versions of themselves, captured forever on black-and-white film.” The photos in this collection are extraordinary, effectively capturing a place in time and the people who inhabited it.

I truly enjoyed working on this special project. Shorr was a delight to work with and peppered our conversations with engaging and often humorous car stories. I am so proud to be a part of this amazing endeavor, and am honored that I was selected to write the introduction. Of course it wouldn’t have happened if it weren’t for a chance meeting with Katie Parkin at PCA. So thank you to Katie and Kathy. I am forever grateful for the connections I have made in this third act of my life.

Limousine is published by Lazy Dog Press.