Shortly after the release of the blockbuster motion picture Barbie, automotive writer Andy Kalmowitz of Jalopnik posted an article about the cars that appeared in the film. While the article argues how Barbie serves as a ‘masterfully disguised General Motors commercial,’ Kalmowitz also examines how the individual vehicles move the story forward. This article was interesting to me for two reasons. The first is that I explored the relationship between women and their automobiles in film in a paper published in The Journal of Popular Culture a number of years ago. In this article I examine ten female road trip films. Focusing on cars rather than the journey, my goal in this project was to reassess the role and significance of the automobile in film, examine how the woman’s car in film has the ability to disrupt both the dominant road trip and cultural narratives, and to broaden the notion of women’s car use to include considerations of identity, agency, reinvention, friendship, family, and empowerment.

More recently, just days after the Jalopnik article appeared, an essay I authored – ‘Pink Power: The Barbie Car and Female Automobility’ – was published online in The Journal of American Culture. The main position put forth in ‘Pink Power’ is the importance of the Barbie car to a young girl’s automotive education and future driving experience. As in most of my writing about the relationship between women and cars, I argue that because the female experience with cars is often unlike that of men, women look at automobiles differently. This difference is often reflected in the roles car play in women’s lives and the myriad of meanings the automobile holds for them.

Therefore as I viewed Barbie in town last night, I paid special attention to the cars. While I noted the role each vehicle played in the narrative, what also caught my attention was how each vehicle represented a specific type of power. These representations were demonstrated not only through the expressions of speed, aggressiveness, and danger, but also by the automobile’s stance, size, color, and signification.

The pink Corvette – the vehicle that literally and figuratively moves the narrative along – is a both a demonstration and source of Barbie’s power. The convertible not only takes her where she wants to go, but is a personal and intimate space in which Barbie is in command and Ken rides in the back seat. In his analysis of the Corvette in American culture, automotive scholar Jerry Passon argues that sport cars in general, and the Corvette in particular, serve as potent symbols of male power and masculine sexuality. He observes that in a variety of creative works—film, literature, popular music –women often call upon the sports car to seize power from the hands of men and take control of their lives. In these fictional locations, Passon writes, “the emotional value of possessing the stylish, powerful machine” makes a woman “feel more ‘in charge’ and able to accomplish her own goals and act on her desires” (153). While the Corvette appears as an ideal car in an ideal world, its pinkness and femininity mask the real power it holds for Barbie and her friends.

The second car to make an appearance in the film is a big, blacked out Suburban. As argued by color psychologists, black is often considered a power color. It implies self-control, discipline, independence, and a strong will; black gives the impression of authority and power. In Barbie, the Suburban serves as the ultimate authority; it is, in fact, the Mattel company car. It is the foil to the pink Corvette; intimidating, unfriendly, and foreboding, it is called upon to transport Barbie away from the source of her power.

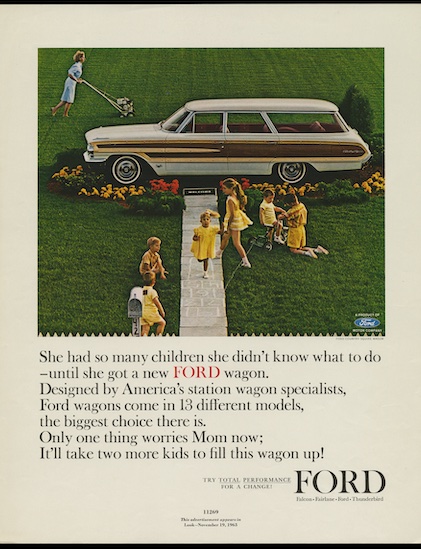

Another car with a major cinematic role is the bright blue Blazer SS EV driven by Barbie’s friend Gloria. The small SUV, of which the Blazer is an example, is often considered the ultimate ‘mom’ car. Purposefully and determinedly identified with women by automakers, marketers, and the media, the ‘lifestyle enabler’ vehicle – which also includes the ubiquitous minivan – reinforces the notion that women bear primary responsibility for housework and childcare. However, with Gloria behind the wheel with daughter Sasha in tow, the Blazer takes on new meaning. As a getaway car, the Blazer demonstrates and celebrates Gloria’s driving finesse and considerable ‘mom’ power as she aggressively and skillfully drives her passengers to safety.

In a film focused on girl power, the most obvious and perhaps egregious representative of male power and toxic masculinity is the lightening adorned black and silver Hummer EV acquired by Ken when out of Barbie Land. Deposited in Los Angeles after relegated to the pink Corvette’s backseat, Ken is quickly exposed to patriarchy and immediately decides he wants to be a part of it. The Hummer, which Jalopnik writer Steve DaSilva describes as ‘oversized, uselessly heavy, and compensating so hard’, represents the masculine power Ken has been missing in his life in Barbie Land. While Ken is briefly successful in acquiring the brutish power the Hummer offers, the vehicle is reclaimed upon Barbie and Gloria’s triumphant return, soon transformed into a massive, monstrous, pink-powered machine.

The automobile holds many meanings in film; what has not been explored significantly is the car’s role in women-themed motion pictures. While the vehicles featured in Barbie contain varied and important meanings to the individual who drives them, what ties them together is how each represents a particular manifestation of automotive, and personal, power.