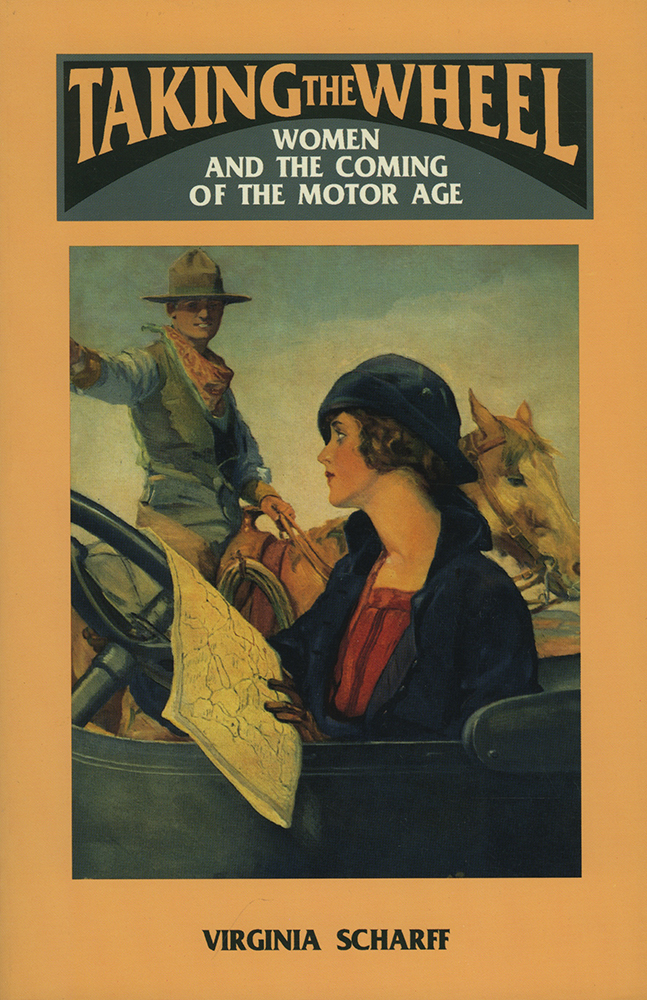

While in graduate school during the 2000s, I devised an independent study focused on my growing interest in the relationship between women and cars. What follows is one of the response papers in which I examine how, in an appeal to male viewers, TV producers relied on the automobile to add masculinity to television programming during the 1960s and 70s.

Since its inception, television has been blamed for a wide variety of society’s ills. The lowering of our nation’s mores, and the rise in illiteracy, indolence, violence and promiscuity have all, at some point, been attributed to television programming. However, during the industry’s infancy, television posed an even greater threat to its growing audience. As Katie Mills argues in “TV Gets Hip on Route 66,” it was the influence of television as a feminizing medium that had both sociologists and programmers up in arms.

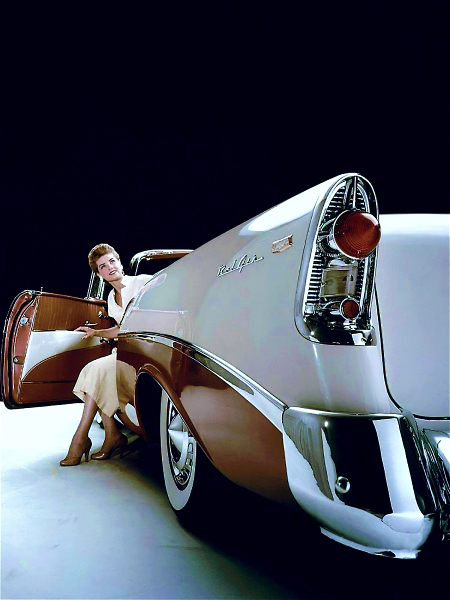

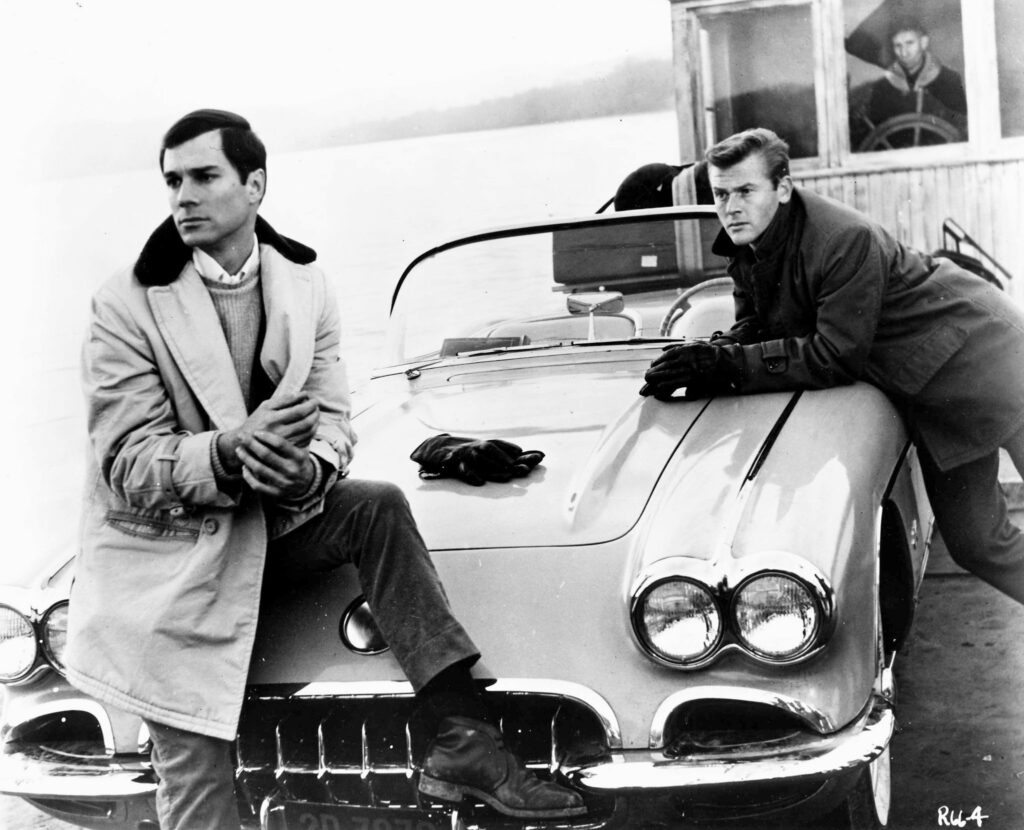

During this period, intellectuals, such as those of the ‘Beat’ generation, expressed anxiety about the inevitable cultural impoverishment of TV audiences. The notion of a “wasteland,” taken from the poem of the same name by TS Elliot, was often invoked to describe women’s and children’s TV programming. What television required, it was suggested, was a dose of masculinity. This infusion of manhood was necessary not only to increase the television viewer base, but perhaps more important, to avoid the feminization of the American audience as well. To attain this goal, a television program was created which featured two handsome young men accompanied by the ultimate symbol of masculine power: the American sportscar. Thus in 1960, Route 66 was born, in which Buz and Tod travel the US highways in a Chevrolet Corvette, rescuing the TV audience from femininity.

Mills writes, “In this ‘cool’ cultural climate of television, the series Route 66 began airing in 1960 as a weekly road story about two non-conforming travelers” (69). The program aired during the prime Friday night time slot, when “exurbanite” fathers were most likely to be home watching television with their families. This road genre series offered CBS a way to dispel the notion of television as a feminine media. In addition, the narrative of the program, which found the male heroes in a different town along Route 66 each week, often provided stories that addressed liberal moral stands, which was quite progressive given the social climate of the postwar era. The Corvette provided mobility, both literally and figuratively, for the two young men, enabling them to travel to new locations and social situations each week. Storylines of the disenfranchised, such as victims of domestic violence or racial bigotry, were made possible by automobility. The automobile provided masculinity to the genre, yet also provided the opportunity for narratives that were not exclusively about men.

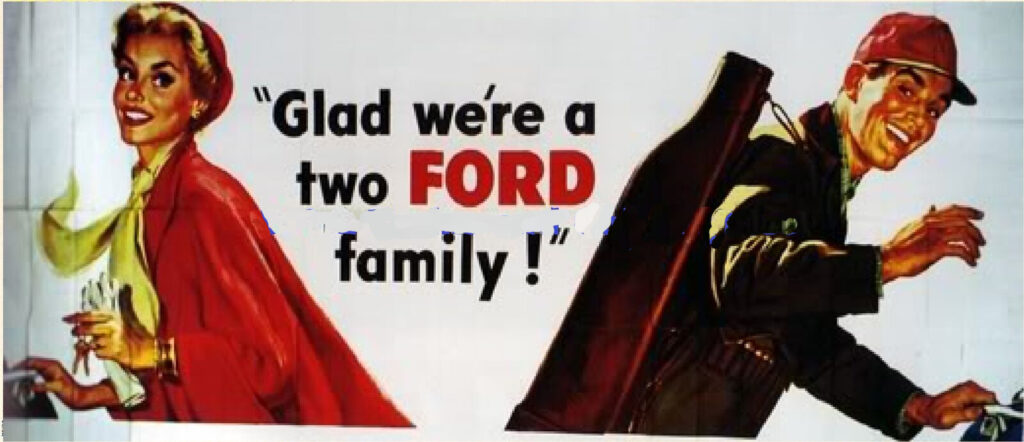

However, despite the initial success of Route 66, it appears that television executives did not believe the show was masculine enough. The CBS president insisted that Route 66 be revamped to include “more broads, bosoms and fun” (76). While Route 66 had tried its best to avoid gender politics, the networks were anxious to attract a larger male audience. Thus, as Mills tells us, television honchos relied on “such male-oriented gimmicks as fast cars, macho conflict and big busted actresses” (77). Such associations have pervaded the use of the automobile in television throughout much of its history. While TV shows that preceded Route 66, such as Danny Thomas, Ozzie and Harriet, and Father Knows Best, used cars to reflect and codify suburban lifestyles and mores, the advent of the muscle car during the late 1960s and its appearance in television dramas reaffirmed the automobile as a symbol of masculinity.

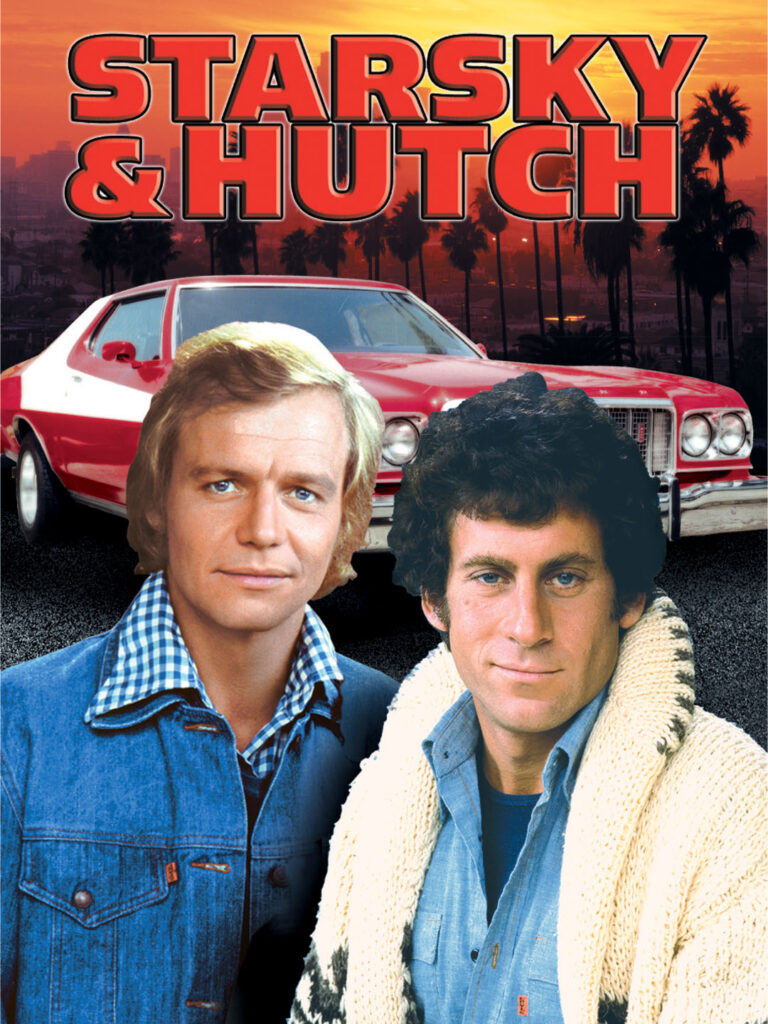

The automobile in Route 66 was never considered a character in the drama. Rather, its significance rested in its use as a metaphor for mobility and masculinity. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, however, the role of the TV car often equaled, if not exceeded, that of its human counterparts. Unlike programs such as Route 66, in which the car contributed masculinity in an understated, almost subliminal manner, automobiles were inserted into 1970s shows to attract a male audience interested primarily in the car. Writing about the Batmobile, in Hollywood TV and Movie Cars, William Krause asserts, “ the enormous popularity of the car primed the pump for countless television cars to become as famous as their human costars” (103). Cartoon-type dramas, such as Batman, The Green Hornet and the Monkees, featured outrageous automobiles constructed from stock muscle cars. In programs that followed, such as Starsky and Hutch, The Dukes of Hazzard, and Magnum PI, “hot” cars often served to divert the male audience from weakness in storyline and character development. Krause writes of the “General,” a 1969 Dodge Charger with a 440-ci V8 Magnum engine and an A-727 automatic transmission featured in Hazzard, “the car was really the only redeeming portion of the show” (120). Whereas the original intent of Route 66 was to attract the male viewer through “masculine” content and subject matter, shows such as Hazzard dismissed such lofty ambitions, and simply concentrated on “fast cars, macho conflicts and big-busted actresses.”

One of the few attempts to disrupt the conflation of masculinity and automobiles on television was in the 1965 ill-fated comedy My Mother the Car. The series, which only lasted one season, revolved around the antics of the protagonist’s mother, reincarnated as a car. However, she does not come back as a cool Corvette or fast Trans Am, but rather, as an antique and antiquated 1928 Porter. Described in the series theme song as “my very own guiding star,” the Porter’s main activity is keeping her grown son, played by Jerry Van Dyke, out of trouble. Speaking only to her son through the car radio, the Porter is the cast character with the most smarts and common sense. However, as Deborah Clarke writes in Driving Women, “despite the fascination with technology – or maybe because of it – the American public wanted no part of a show that insisted that a woman and a car could be one and the same” (74). As a car’s primary function in television is to infuse it with masculinity, My Mother the Car suggests that the automobile as a mother has very little appeal.

As the car in television suggests, the automobile is not only an American symbol of masculinity, but is often called upon to make TV programming more masculine as well. In American society, that which is feminine has less value. Faced with the possibility of a feminized, and therefore, undesirable medium, TV producers and programmers have traditionally called upon technology, in the form of an automobile, to add masculinity, and therefore intrinsic value, to what is viewed on the television screen.

Clarke, Deborah. Driving Women: Fiction and Automobile Culture in Twentieth-Century America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.

Krause, William. Hollywood TV and Movie Cars. Minneapolis: Motorbooks, 2001.

Marling, Karal Ann. “America’s Love Affair with the Automobile in the Television Age” in Design Quarterly 149 (1989): 5-22.

Mills, Katie. The Road Story and the Rebel: Moving Through Film, Fiction, and Television. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2006.