I took a trip to South Bend, Indiana this past weekend to visit the Studebaker Museum. The museum is part of a larger complex which includes The History Museum, an institution dedicated to preserving the region’s heritage through exhibits and educational programs. The Studebaker Museum’s mission also focuses on the region, as it shares the story of the automotive and industrial history of South Bend and the greater area ‘through the display and interpretation of Studebaker vehicles along with related industrial artifacts.’ The museum not only features an impressive display of Studebaker vehicles, but special exhibits call attention to other aspects of automotive manufacture and culture. My visit to the museum was planned around one of these exhibits – the ‘Family Hauler’ display featured a collection of station wagons from a wide variety of automotive manufacturers. Center stage was a 1957 Chevy Nomad, one of my personal favorites [particularly since we have a 1956 model stored in our classic car garage].

Although the focus of the museum is on a specific area and the automobile it produced, it appeared that a conscious effort had been made to include the influence of women in the Studebaker industry and automotive culture. This was achieved primarily in four areas: women as automotive workers, women as icons of style, women as Studebaker drivers, and women as members of charitable organizations with industry affiliations.

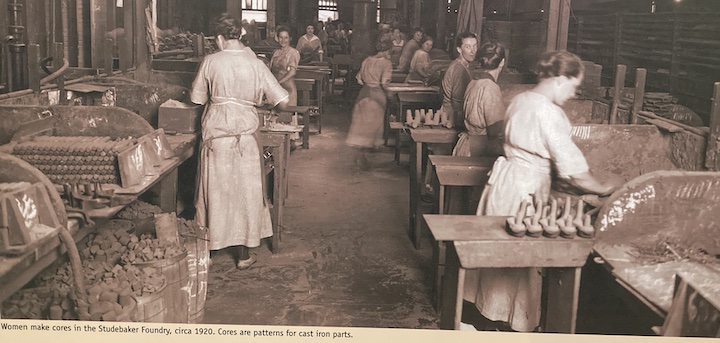

The women who worked at Studebaker were featured in photographs and interactive displays throughout the two-story museum. Photos of female factory workers in the 1920s revealed that although women were valued employees, they worked in a gender-segregated environment. Although other museums often feature photos of factory men and women working side-by-side, I suspect that wasn’t a common practice in any automotive workplace during the years [1897-1966] of Studebaker production. The museum also features a number of photos of women employed in clerical positions. As the caption to a 1952 photo of a female clerical worker reads, ‘many people who worked at Studebaker did not build vehicles. The company employed hundreds of clerical workers, like this woman processing production orders.’ Another display focuses on sisters Elizabeth Hahn Mast and Rosa Hahn who worked as administrative assistants, and, as the caption reads, ‘connected to the company in many ways including many that extended outside of their offices.’ Exhibits that featured women as union members were also in evidence.

Notable in the category of Studebaker workers was a display featuring Helen Dryden, an artist and industrial designer who lent her talent to automotive interior and instrument panels design. An advertisement for the 1936 Studebaker President reads, ‘In its singularly beautiful, lavishly roomy interior, the genius of that famed industrial designer, the gifted Helen Dryden, has been expressed in fine fabric, beautifully tailored, and in fittings of advance motif that are of impeccable good taste.’ The mention of Helen Dryden by name – as a female in the masculine auto industry – was certainly unusual for automotive advertising of the time.

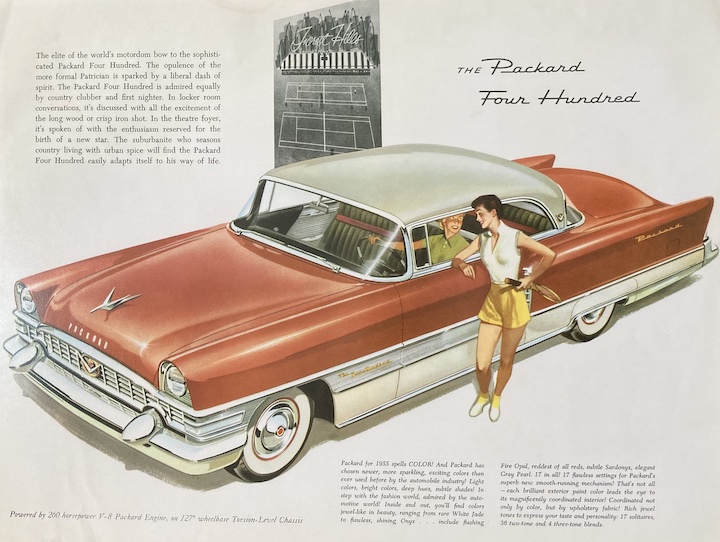

Promotional materials for higher end vehicles often feature women to lend an aura of style and class; those included in the Studebaker were no exception. And like many other museums, there are female mannequins throughout the museum adorned in the fashion of the day, to place the vehicles in a particular era as well as to suggest the type of woman who would be associated with a Studebaker automobile. Women were prominently featured in advertising for the Studebaker Lark, a compact car produced from 1959 – 1966. Although the ads didn’t specifically refer to the automobile as a ‘women’s car,’ the vehicle’s smaller size and lower price point suggested it was an appropriate vehicle for the woman behind the wheel.

There are also many photographs of driving women, most unidentified, on the museum walls and in display cases, suggesting that the Studebaker was enjoyed and appreciated by men and women alike.

There are also a number of items that refer to the Mary Ann Club, which was a social organization for the women who worked in the Administration Building. As noted in the literature, the Mary Ann Club ‘became one of South Bend’s most prominent charitable organizations.’

The special Family Hauler exhibit featured a number of advertisements from multiple car manufacturers; most featured women as the primary drivers. This conflation of women with the ‘family vehicle’ became solidified during this era; it was picked up by minivan and SUV manufacturers in subsequent decades to describe the perfect vehicle for ‘soccer moms.’

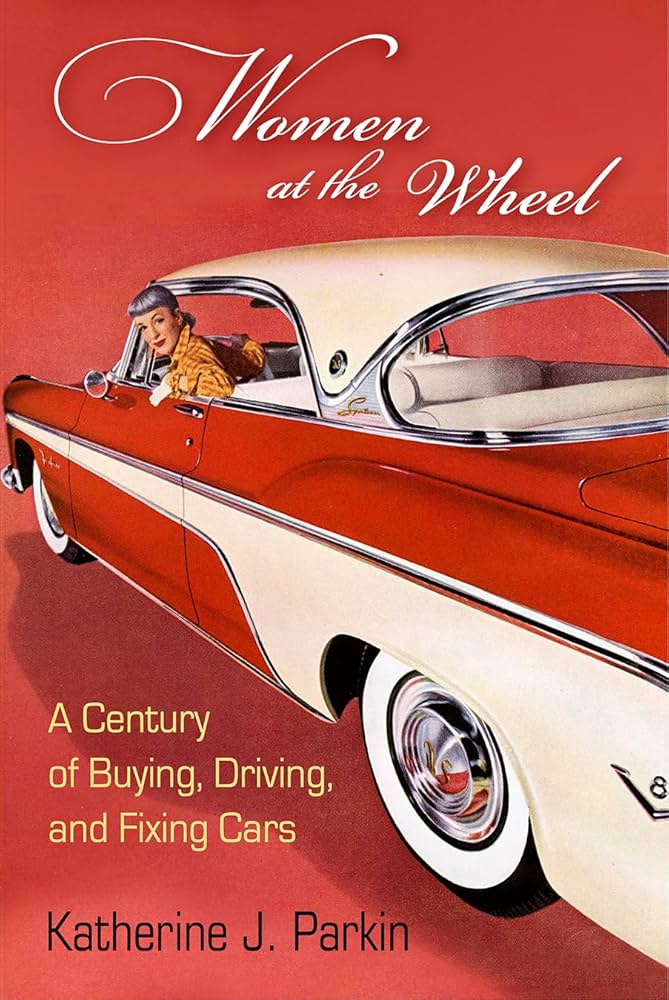

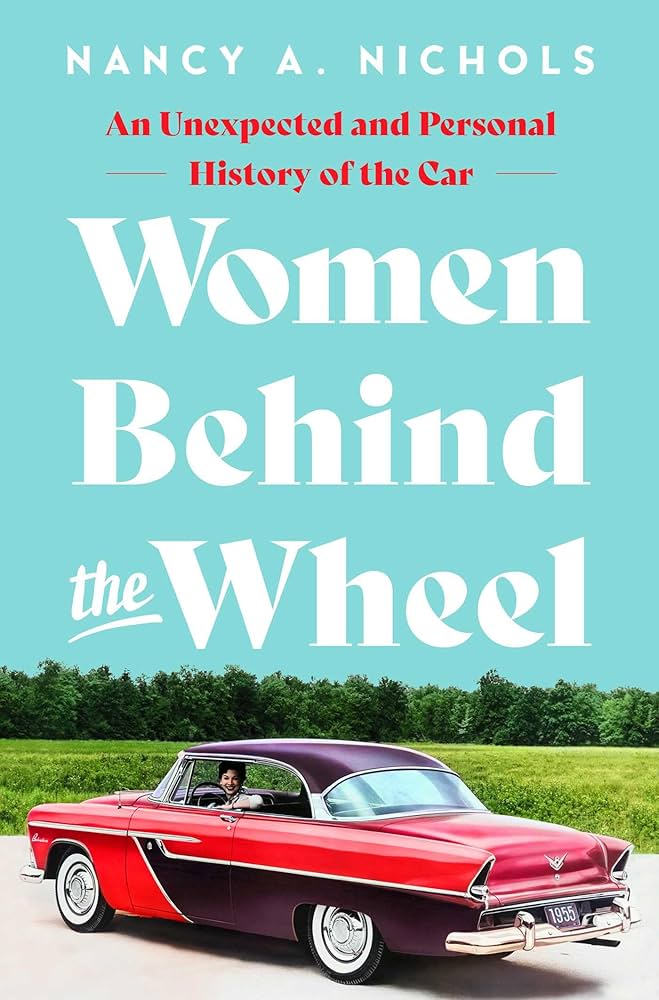

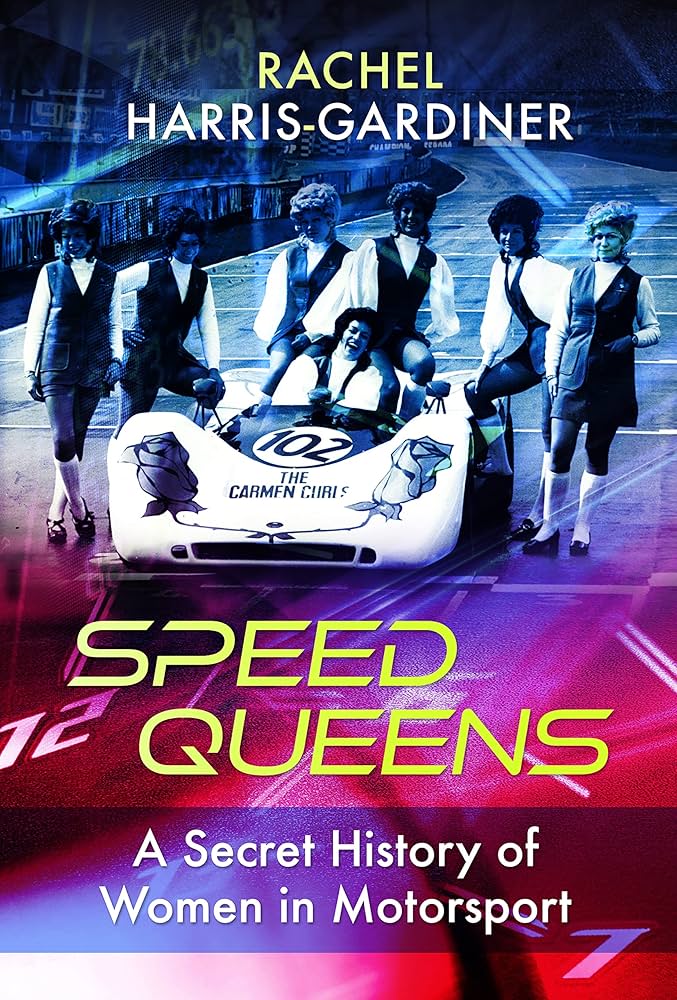

Other references to women include Studebaker women with influence, goddesses in the form of hood ornaments, and stories featuring female Studebaker owners. Encouraging signs included an interactive display narrated by the female programs and outreach manager, as well as a special section in the gift shop devoted to women and automobiles.

I found my visit to the Studebaker Museum to be both educational and enjoyable. In the context of my current project on the representation of women, the Studebaker Museum demonstrates how – through small additions and attention to female contributions – women can, in fact, be incorporated into the history of the automobile.