Recently I drove to downtown Detroit to visit one of my favorite museums. The Detroit Historical Museum is a popular destination for school groups, families, and native Detroiters. I have been going to the DHM since I was a kid in the Detroit Public Schools; I even shot a commercial in The Streets of Old Detroit – the museum’s ‘most beloved exhibit’ – back in my advertising days. As stated on its website, the DHM’s mission is ‘Chronicling the life and times of the Detroit region, safeguarding its rich history.’ Although it is not technically a ‘car’ museum, it is an institution that highlights the Detroit auto industry as an important contributor to the region’s history and culture. While the typical automotive museum is constructed around a vast and impressive collection of cars, the Detroit Historical Museum focuses on the influence of the automobile on the city, the people, and the culture. As a museum of ‘place,’ it is less about the cars than the community that gave birth to the American auto industry.

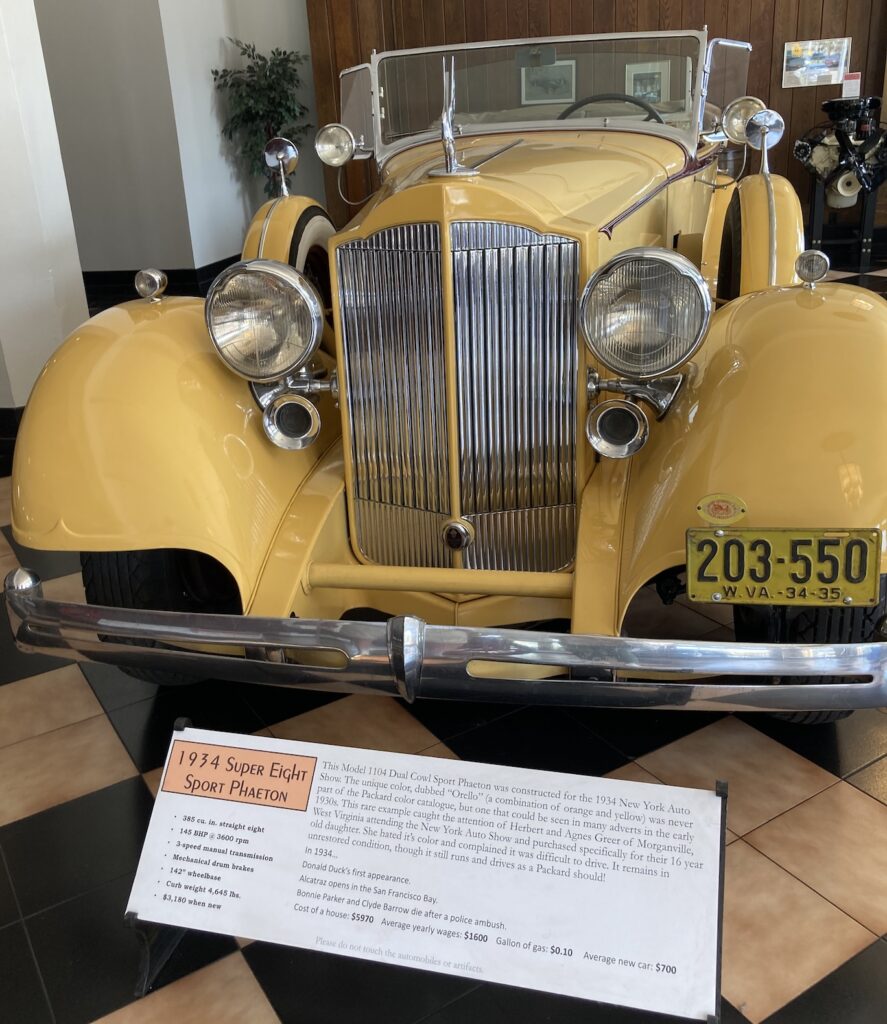

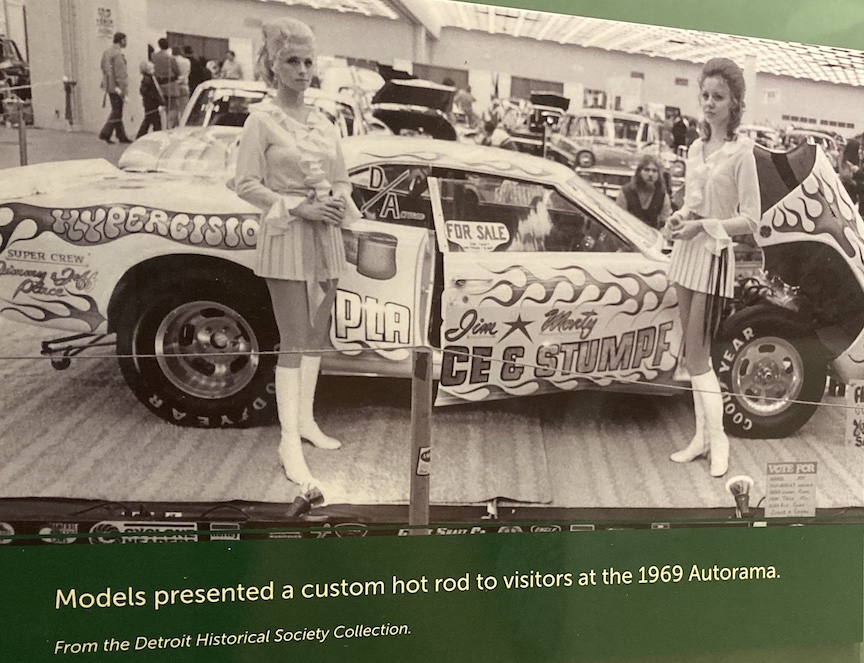

Two signature exhibitions feature Detroit’s connection to the automobile. America’s Motor City has three main objectives – to examine how cars built Detroit, to look at how metro Detroit built cars, and to reflect on how and why Detroit became the motor city. Much of this is related through stories of individuals who lived and worked in the region. Detroit’s car culture is also an important part of the exhibit. Displays and information reveal the personal connection Detroiters have to cars.

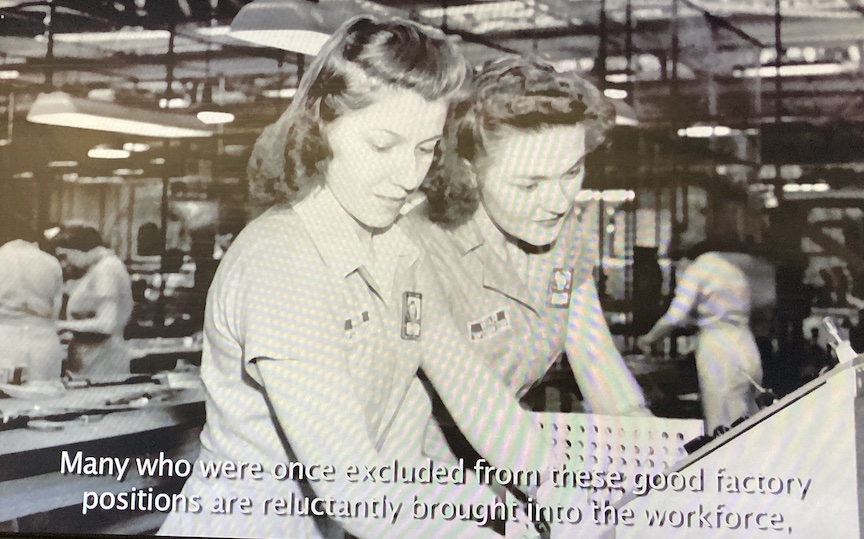

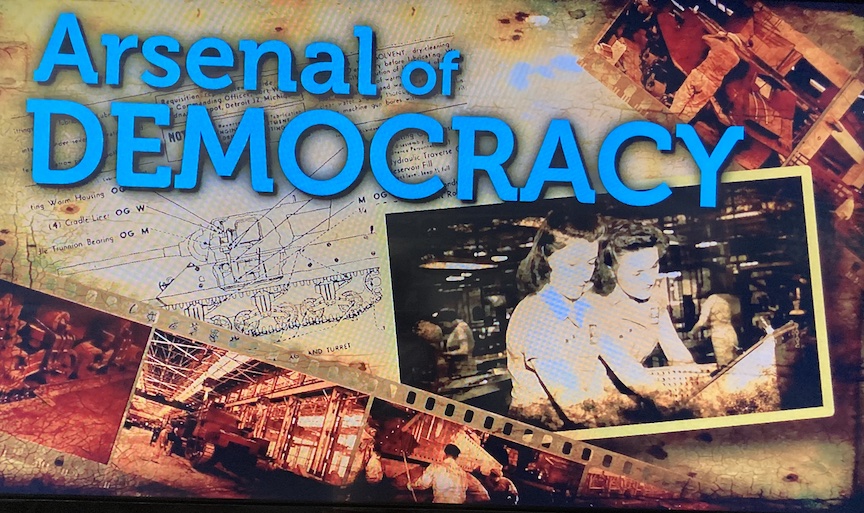

Detroit: The Arsenal of Democracy focuses on how Detroit became a center of wartime production, retooling its auto factories to produce aircraft and other war materials.

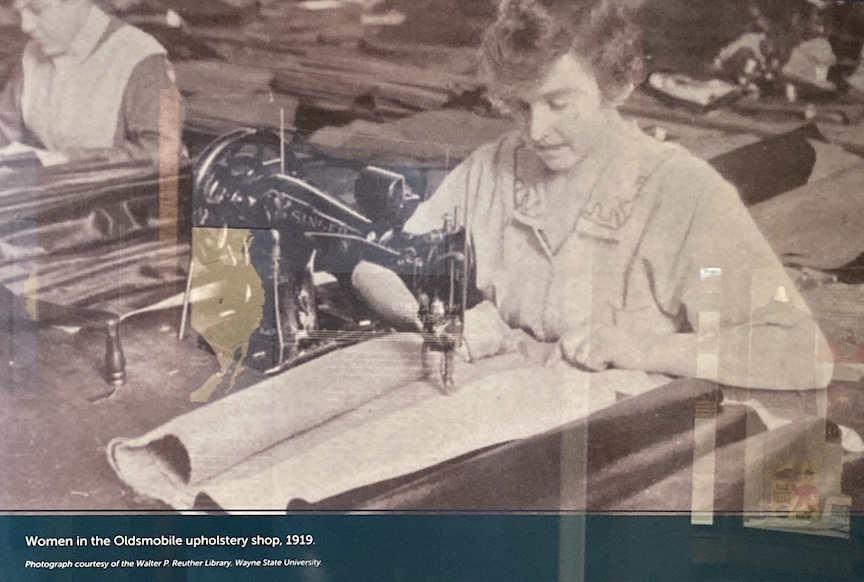

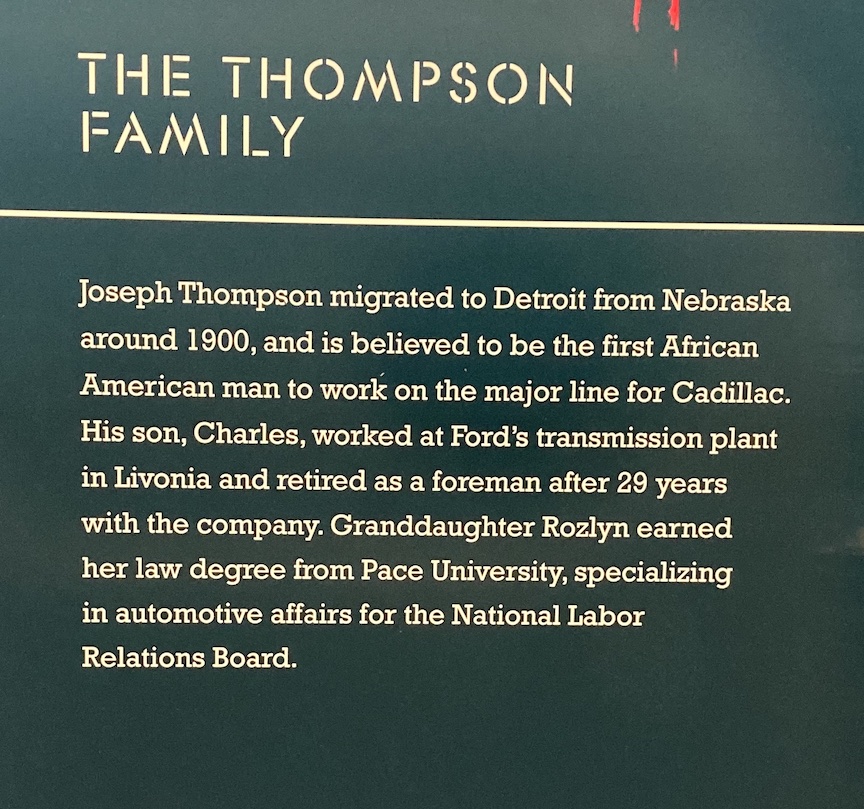

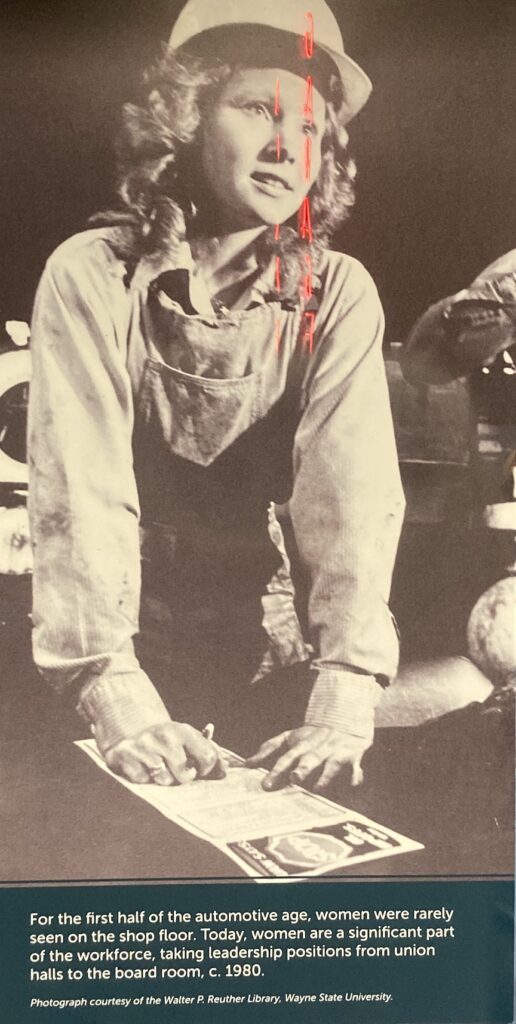

Women’s representation in the Detroit Historical Museum is found primarily in the role of workers. Although the museum recognizes that women were ‘all but absent’ in the first half of the auto age, a conscious effort has been made to include women’s contributions in the factory, and as part of automotive families. My grandfather was one of the thousands of Polish immigrants who came to Detroit during the early 20th century to work at Dodge Main. The exhibit features the stories of immigrant families – photos and artifacts tell the stories of the men and women who came to Detroit for the promise of jobs and the hope of a better life.

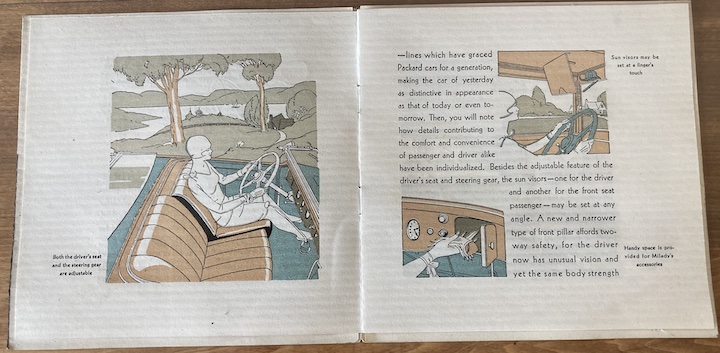

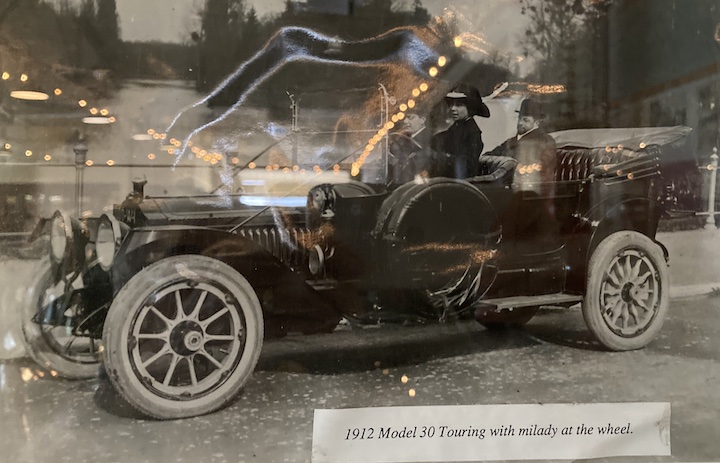

There are many photos of women working in the factories in gender segregated workspaces. There are also stories of the daughters of early auto workers who as adults became employed by the auto industry in some capacity. Women’s acceptance as factory employees is also reflected in photographs of recreational activities, such as a plant female softball team. The images of female factory workers suggest that there were certain ‘female’ characteristics – small hands and attention to detail – that were valued by auto makers, even though women’s contributions have remained relatively unknown. Other female representation included posters and photographs of the Detroit Auto Show and other events, as well as other promotional materials, photos, and advertising.

As I have discovered, auto museums of ‘place’ provide a greater opportunity to incorporate women into the region’s automotive history. Auto history is not just about old cars and famous men; rather, it is about the community and the collective culture that developed around the automobile.