Last week I made a trip to Dayton, Ohio to visit America’s Packard Museum. Housed in a former Packard dealership, the museum claims to have the largest collection of Packard autos and memorabilia in the world. The Packard Car Company which the Dayton museum celebrates originated in Detroit; the Packard Automotive Plant, now under demolition, was a massive structure that occupied 38 acres in the downtown area. Packard was known for its production of luxury automobiles; owning a Packard was a visible sign that one had ‘made it.’ The first Packard automobiles were produced in 1899; the last came off the line in South Bend, Indiana in 1958.

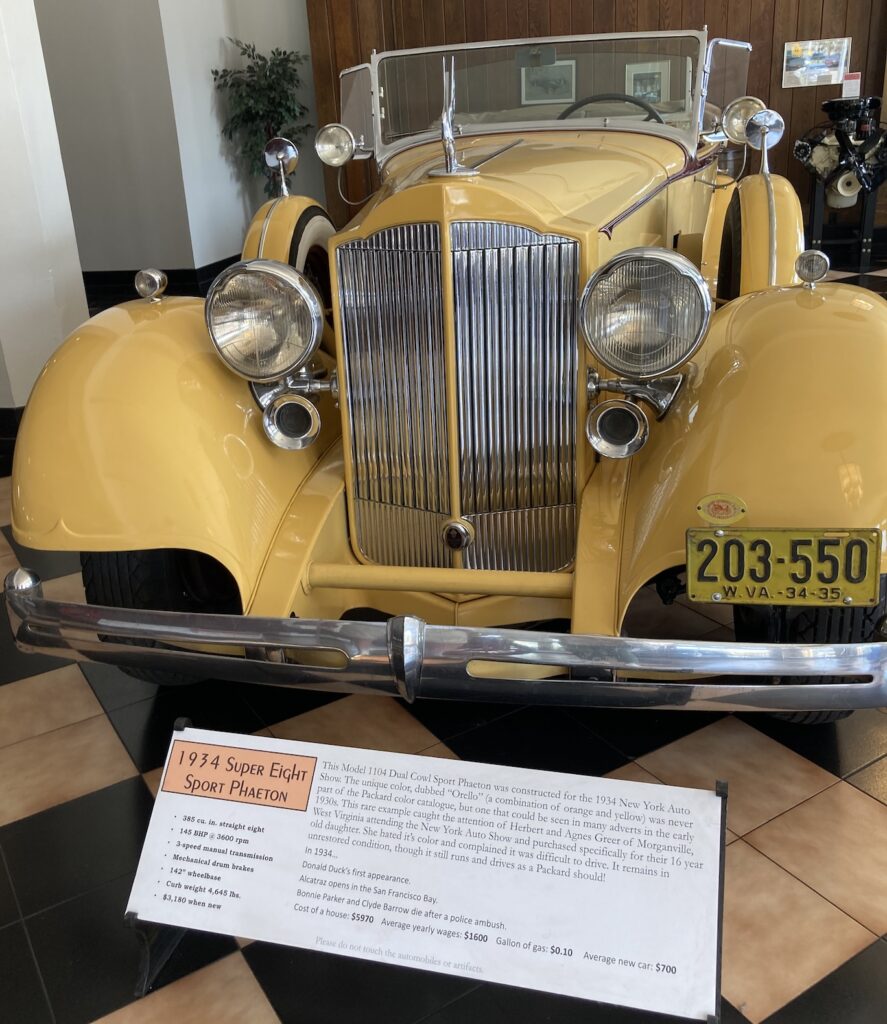

The mission of the APM is “to educate present and future generations about the Packard Motor Car Company, its products, and philosophies.” The museum is one I would consider ‘old style;’ there is little tech and the display cards appear to be somewhat old. However, like many other automotive museums, the placards include a couple of short historical “bites” that place the automobile in a particular time and place. Glass cases containing women’s fashion pieces also serve as a period reference.

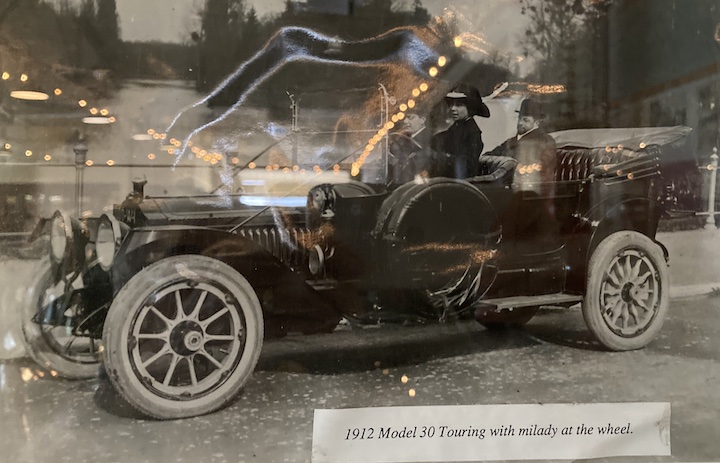

Despite its somewhat old fashioned exhibition style, the museum has made some attempt to include representations of women. This is accomplished primarily through stories on placards, as well as hood ornaments, unidentified photographs, and promotional materials.

The Packard hood ornament is perhaps the most visible female representation. Hood ornaments, sometimes referred to as motor “mascots,” were used to identify an automotive brand and differentiate it from others. Hood ornaments on Rolls Royce and Packard models, for example, often served as symbols of luxury. Packard featured three distinct hood ornaments on its vehicles – the cormorant [a flying bird], Adonis [representing youth and beauty], and Nike, the Winged Goddess of Victory. In Mascots in Motion, Steve Purdy writes, “Packard’s goddess of speed mascot, created by Joseph E. Corker and patented in 1927, is based on a sculpture of Nike in the ancient city of Ephesus. Colloquially the ‘Donut Chaser,’ she first adorned 1926 cars. […] Designer Corker replaced her laurel wreath with a wire wheel. […] In Greek lore the laurel wreath was given to the victor of a competition or conflict.”

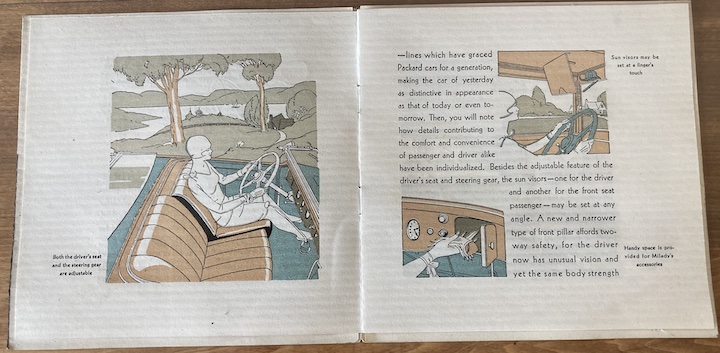

Packard advertising frequently featured women as a means to associate the automobile with luxury, status, and class. An ad for the Dietrich Convertible Sedan reads, “Cultured women instinctively recognize and appreciate fine work – whether it be the decorator’s, the modiste’s, or the motor car designer’s.” The entire ad equates women’s “good taste and discrimination” to the Packard’s reputation as a car of good quality and distinction. Although the Packard theme line reads, ‘Ask the Man Who Owns One,” women were often called upon to express the finer qualities of the automobile. Promotional material often incorporate women to demonstrate the automobile’s distinctive features, particularly those assumed important to female Packard drivers. As a beautifully illustrated Packard brochure states, “handy space is provided for Milady’s accessories.” There are also a number of photographs in the museum that feature women behind the wheel – while many are unidentified, famous women in Packards also make an appearance.

There are a number of cars on display with women-centered stories. The 1934 Super Eight Sport Phaeton on the showroom floor – in the unique shade of “Orello” (a combination of orange and yellow) was originally purchased as a birthday gift for the daughter of Herbert and Agnes Greer. Apparently the 16-year-old “hated the color” so it is not known how much she actually drove the automobile. Another interesting story is that of a 1934 Super Eight Club Sedan owned by Mrs. Maude Gamble Nippert, the daughter of the inventor of Ivory Soap. She always drove the car herself, and as a firm believer in the hereafter, stipulated upon her death that the car was to be regularly maintained to be ready for her return. Each of these car stories are important reminders that the automobile often held a special place in a woman’s life, whether as an object of opposition or devotion.

As I made my way through the exhibits, searching for female images in printed material and photographs, I was reminded how auto museums have the ability to incorporate women into automotive history if they look beyond the male-defined definitions of what is significant. I’m not sure what leads to the absence of female representation – is it a lack of relevant donations or is it because both donors and archivists have limited notions of exactly what constitutes women’s automotive history? But I am encouraged that museums such as the Packard have taken the first step in expanding the idea of what automotive history is, through the incorporation of women’s stories, influences, and contributions as part of the company’s automotive heritage.