A recent article from Autoblog News announced the winners of this year’s Women’s Worldwide Car of the Year [WWCOTY]. The jury for this competition consisted of 84 women motoring journalists from 54 countries; all eligible vehicles were required to be produced and sold in at least two continents or 40 countries between January and December 2025. The awards were broken down into six categories: compact car, compact SUV, large car, large SUV, 4×4, and exclusive car. The six category winners will advance to the final round for the overall Car of the Year during the week of International Women’s Day.

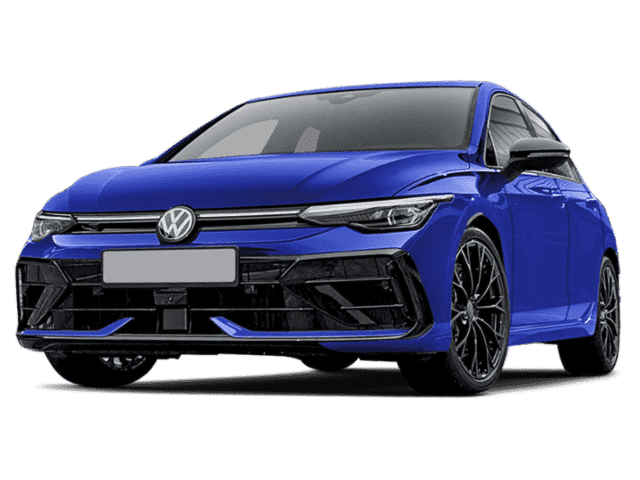

While the competition is judged by a panel of all women [the only all-female jury in the automotive industry], the cars are not evaluated in terms of what auto manufacturers typically market to women. Rather, as the judges made clear, the evaluations are based on universal criteria of importance to all drivers regardless of gender. Key considerations in the evaluation process included safety, design, quality, comfort, performance, efficiency, environmental impact, ease of driving, and value. The winners selected by the judges included the Nissan Leaf [compact car], Skoda Elroq [compact SUV], Mercedes-Benz CLA [large car], Hyundai Ioniq 9 [large SUV], Toyota 4Runner [4×4], Lamborghini Temerario [exclusive car].

What is interesting about the list of winners is that they are all imports; none of the vehicles were produced in the United States. Granted, this was an international panel of judges and not all cars are available to American buyers. But the results confirm a longstanding and growing trend: women prefer imports to domestic automobiles.

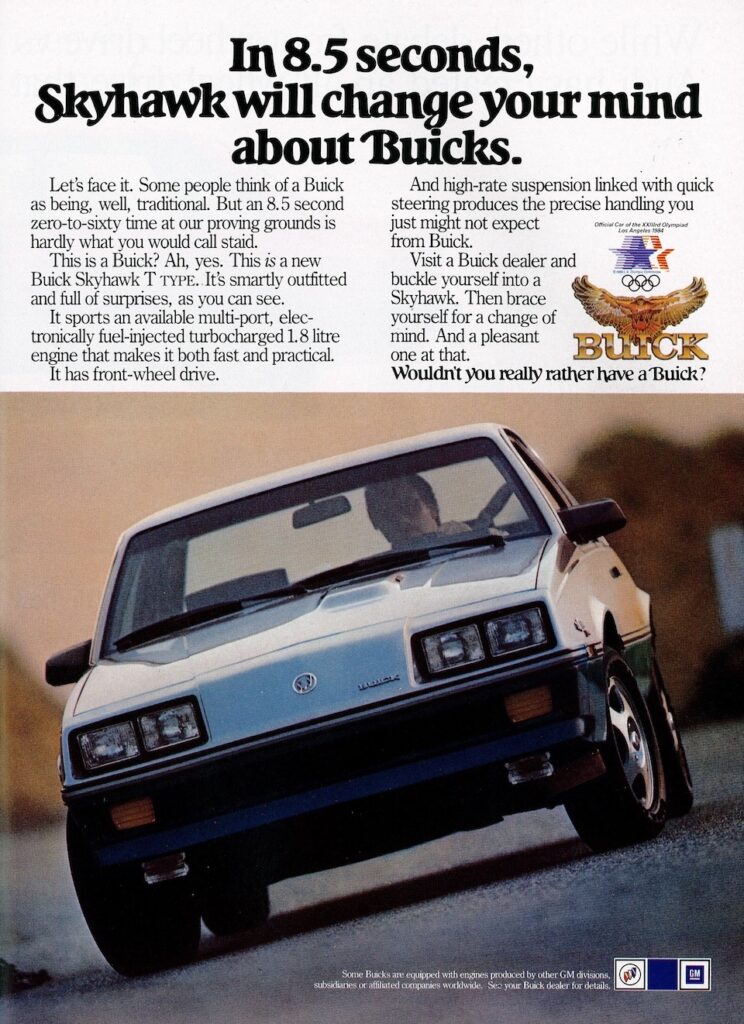

My own research confirms this preference. As I noted in an earlier blog, American auto manufacturers have never quite figured out the female consumer. Domestic automakers have traditionally built big cars for the big, wide open US highways, without taking into consideration that driving conditions do not necessarily dictate what all drivers want. US carmakers have historically refrained from developing small cars because, as James Flink, author of The Automobile Age, remarked, ‘large cars are far more profitable to build than small ones’ [the male preference for large pickup trucks is a current example]. Such a sentiment ignores the fact that the majority of US automobiles produced before 1990 were simply too large and cumbersome for the average woman to drive comfortably. Dissatisfied with domestic automobile choices – big and expensive, or cheap and spartan – female drivers began to notice that the economical, well-appointed and well-designed Asian and European cars ‘fit’ them better. As they switched to imports, women found the vehicles to be more reliable, durable, and have greater resale value than the domestic cars they left behind.

In a past research project, in which I interviewed 21 women aged 80-90 about their early automotive experiences, the majority expressed an early loyalty to American models [often taking advantage of employee discounts], but switched to imports once such cars became readily available. Although Lee Iacocca’s introduction of the minivan in the mid 1980s was successful among a certain population of suburban moms, eventually replaced in popularity by the ubiquitous SUV, foreign manufacturers continued to broaden their offerings to include compacts, sedans, and SUVs to appeal to a wide range of women drivers. American manufacturers have since eliminated sedans from their respective lineups. Consequently, women have and continue to demonstrate a preference for import brands, citing qualities such as reliability, fuel efficiency, practicality, higher resale value, and smaller vehicle sizes when shopping for a vehicle.

Although the jury emphasized that there is no such thing as a ‘woman’s car’, as a panel of women, they no doubt looked for qualities that were important to them as female car buyers [the same could be said for men]. However, as the article noted, as a jury composed entirely of women, the contest provided the awarding body with a voice in what has traditionally been a male dominated industry. Time will only tell if the American automotive industry will listen to such a voice.