A few years back a fellow female automotive scholar [there are so few of us] encouraged me to join the Society of Automotive Historians. As I am not a historian, a true car enthusiast, or particularly knowledgeable about cars, my first response was to graciously decline. However, this individual pressed upon me that as the organization was overwhelmingly male in membership, it would be in the best interest of the SAH to have a greater female presence. I therefore somewhat begrudgingly joined, and spent the first couple of years reading club publications, attending a few SAH events, and getting to know some of the major players.

When this same individual was elected to the Board, she persuaded me run in the next election. Not surprisingly, I lost. But as I started getting more active in the organization, I took on a few projects so that folks could see that although I was not nearly as knowledgeable as the majority of the membership, I was hard working and serious about my commitment to the SAH.

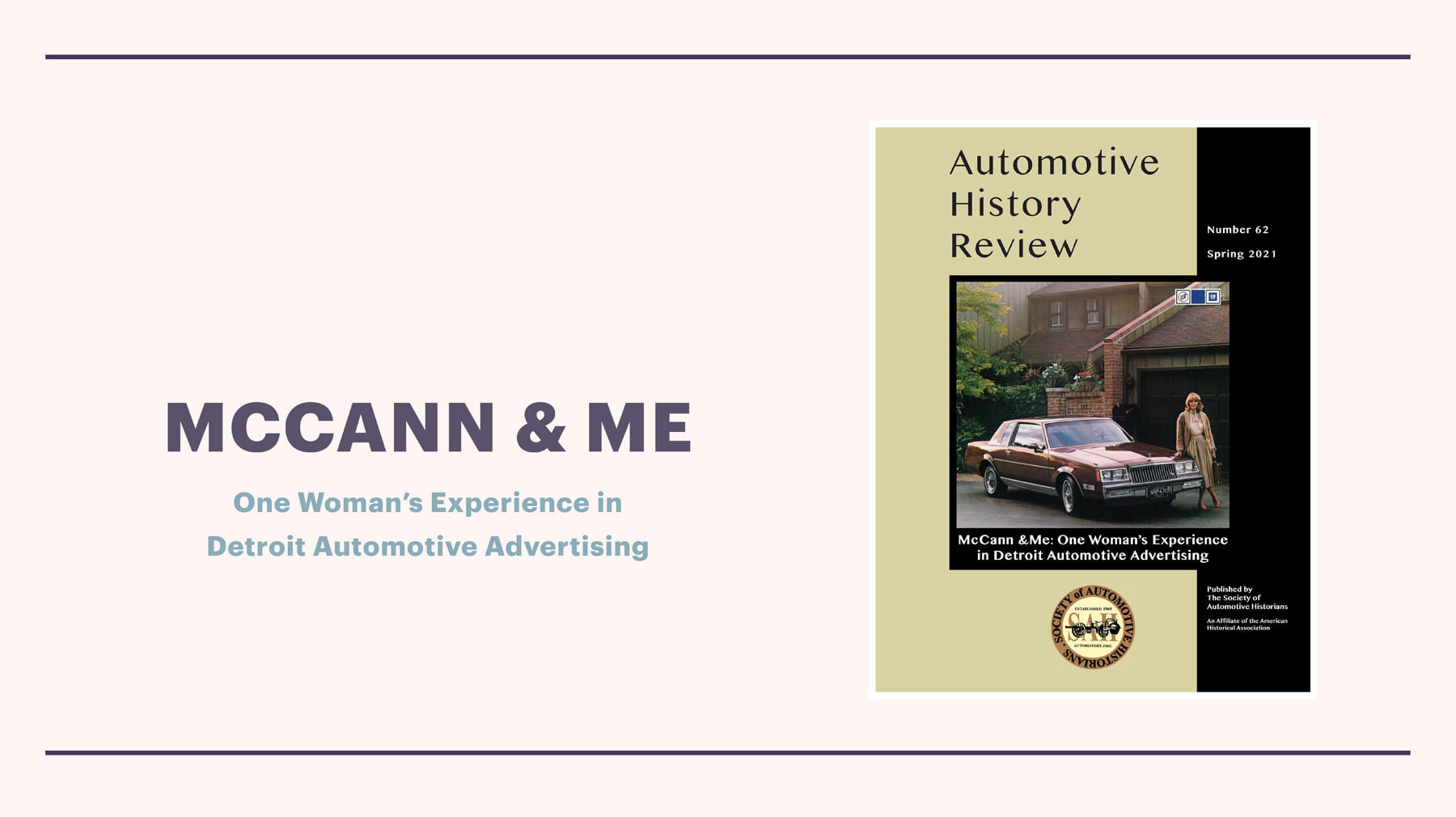

I was elected to the Board at the following election, and over the next few years took on responsibilities as chair of the Awards Committee and Bricks and Mortar Working Group. I participated in a number of SAH sponsored conferences, wrote a couple of book reviews for the SAH Journal, and had a number of articles published in the Automotive History Review, the premier publication of the SAH. I worked especially hard on the Bricks and Mortar Working Group, securing partnerships with two institutions to house the SAH archives. However,I believe the turning point in my relationship with SAH was the publication of an article in AHR that reflected on my experiences as a woman in automotive advertising in the 1980s. This insight into an unknown and often mysterious area of the automotive industry – a business which non-ad people find fascinating – gave me some legitimacy. I finally felt like I was not an SAH interloper, but perhaps in some way deserved to belong.

About a year ago the notion of my running for SAH VP was tossed around. As it is expected that the VP will eventually be President, I was dismissive of the idea, since I do not have the personality [I am socially awkward] or organizational skills for such a position. Thus when I was officially asked to run, I declined. I thought the matter was settled, but I was so wrong. Over the course of two weeks I was contacted by a number of individuals asking me to reconsider my decision. Putting the flattery of such attention aside, I pondered long and hard as to whether I could, in fact, handle the job. I eventually accepted, and at the Annual Meeting earlier this week I was officially installed as the newly elected Vice President of the Society of Automotive Historians.

The next two years will be a challenge. But I have a lot of support, particularly from the newly elected President. He and I share a vision for the SAH which we hope to implement over the next 24 months. So here I am, a not particularly glib individual with an interest but not an expertise in automotive history presiding over an 50+ year organization with a commitment to the preservation and dissemination of automotive history for present and future generations. It’s been a fascinating journey to get here, but the real trip has only just begun. Wish me luck!