While working on my master’s degree at Eastern Michigan University in the early 2000s, I devised an independent study focused on my growing interest in the relationship between women and cars. What follows is one of the response papers in which I consider the appeal of non-made-in-America vehicles to female motorists. While this paper focuses on a particular period of American auto history, what is interesting is that, since this paper was written, American automakers have ceased production on small cars and sedans, conceding their manufacture to Asian and European car companies.

As I conducted research on the “chick car” last year, I discovered that the automobiles most often included in this category are foreign models. The Mini Cooper, VW Beetle, Mazda Miata and Toyota RAV4 appeal to women because they are affordable, cozy, well-designed and most important, fun to drive. Therefore, as I read Flink’s recounting of the foreign car invasion in The Automobile Age, I couldn’t help but wonder if the success of the foreign car in this country is based in part on its appeal to a segment of the car-buying public traditionally ignored by the US automotive industry. I wonder, in fact, if women’s embrace of the small, quick, comfortable and affordable foreign car is somewhat responsible for its increasing popularity, as well as for the decline of domestic vehicle sales. While it is certainly an overstatement to imply the bleak state of the US auto industry is due to its inherent patriarchy and dismissal of women’s interests, there remains enough evidence to suggest that the failure to build a car that appeals to women, in the form of a smaller, quicker, more economical and more technologically advanced vehicle, is a contributor to the industry downslide.

Automobile history tells us that US car manufacturers have traditionally designed separate models for European and Asian markets. As James Flink writes, “like most other European auto manufacturers, and in marked contrast to their American operations, Ford-Europe and GM-Europe both concentrated in the postwar decade in producing small, fuel-efficient cars” (295). The significant difference in cars built for foreign rather than domestic consumption suggests automakers responded to such variations as geography, fuel cost, road conditions and government restrictions rather than on cultural or social requirements and desires. Simply put, US automakers built small cars for foreign markets because the roads are narrow, not because the citizens want or need a smaller, more efficient automobile.

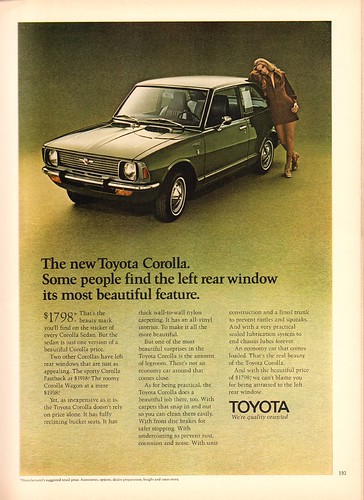

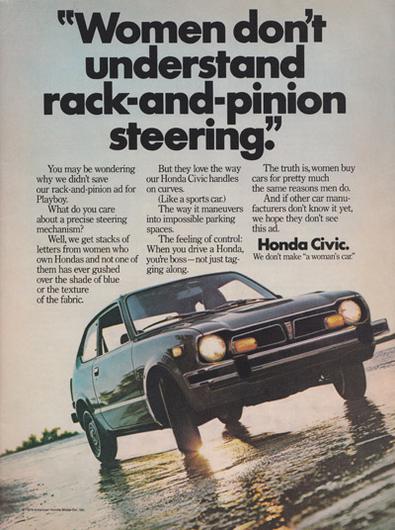

Domestic automakers built big cars for the big, wide open US highways, without taking into consideration that driving conditions do not necessarily dictate what all drivers want. Industry leaders failed to notice that many of the qualities that appeal to foreign car buyers are also attractive to female drivers. US carmakers have historically refrained from developing small cars because, as Flint remarks, “large cars are far more profitable to build than small ones” (284). Such a sentiment ignores the fact that the majority of US automobiles produced before 1990 were simply too large and cumbersome for the average woman to drive comfortably. I know that when I learned to drive, I had to place a pillow behind my back in order to engage the clutch pedal. My sister, who is even shorter than I, sat on a cushion in order to see over the car’s hood. During the 1950s, Christy Borth of the Automobile Manufacturers Association is quoted saying, “it is foolish to use two tons of automobile to transport a 105 lb blond” (Flink 283). While the Japanese may have considered the smaller stature of its citizenry when designing automobiles, American car makers systematically ignored the more diminutive half of its population as it continued to blissfully crank out big, bulky automobiles.

What Flink doesn’t mention, but which bears consideration, are the meanings associated with a “big” car. Not only is “big” associated with masculinity (today’s Ford F150 Trucks are a prime example), but also reflects America’s position of itself, the assumed “big boy” of the world. No doubt US car manufacturers think of themselves as big and male (and the Japanese, on the other hand, as small and feminine, and therefore of less value). Because the US car industry appears to have stock in the axiom “bigger is better,” American automobile manufacturers, as Flink writes, “remained convinced well into the 1960s of their invulnerability to foreign competitors in the world as well as the US market” (294).

In A Nation on Wheels, Mark Foster suggests that such arrogance prevented automakers from considering other options in automobile production. Isolated from both criticism and the real world, auto executives convinced themselves that American car manufacturers “knew all there was to know about making and marketing cars” (143). Cloistered and isolated with individuals very much like themselves, corporate automakers “were seldom exposed to those who might disagree with them, particularly within the corporation” (143). Detroit auto men seemed incapable of viewing the car industry through eyes other than their own. As Flink tells us, while American automakers continued to build one standardized product in the largest possible volume, “Europeans fashioned domestically produced products for very different national market conditions” (299). The Europeans considered the divergent needs, driving styles and economic means of its potential buyers. US auto manufacturers, on the other hand, told consumers what to buy based on their own monolithic vision. European and Asian car manufacturers attempted to appeal to a wide variety of drivers, which of course, included women. Detroit automakers continued to profess they knew what the American public wanted without bothering to ask them.

Foreign cars are often less expensive than equivalent American-made products. Such lower priced automobiles, Flink reminds us, are often “a combination of lower wages, higher labor productivity and a unique system of material controls and plant maintenance” (335). As women have lower incomes than men, the lower purchase price and maintenance costs make foreign automobiles more attractive. And as many women remain responsible for maintaining the household budget, the value of an import often prompts its purchase. Most important, however, is that European and Asian manufacturers have traditionally addressed the needs of its customer base and have offered them options.

In Trouble in the Motor City, Joe Kerr writes, “over-confident from decades of total domination of American markets, the car-makers were still building their unwieldy and antiquated products when the oil crisis hit in 1973” (135). If we consider the masculinity embedded in American car culture, represented not only by the big, unwieldy vehicles but also those who produce them, the reluctance to build a smaller and more efficient car becomes understandable. The Japanese automobile, built by and for those smaller in stature, may be considered feminine and therefore undesirable. While such characteristics may explain why the foreign car has special appeal to women, it also suggests why the US automotive industry has been so reluctant to embrace the smaller automobile. As Bayla Singer, in Automobiles and Femininity writes, “in order to classify the qualities of the automobile driver as fundamentally masculine, thus perhaps allowing even the frailest male office worker to assert his masculinity, female use of the automobile must be classified as marginal or trivial” (39). Thus the disparagement of the foreign car, which includes the category of “chick car,” stems not only from its compact size, but also from the stature of the person who drives it.

Flink, James J. The Automotive Age. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 1988.

Foster, Mark. Nation on Wheels: The Automobile Culture in American Since 1945. Belmont, CA: Thomson, Wadsworth, 2003

Kerr, Joe. “Trouble in the Motor City.” Autopia: Cars and Culture. Peter Wollen and Joe Kerr, eds. Reaktion Books, 2002. 125-138.

Singer, Bayla. “Automobiles and Femininity.”Research in Philosophy and Technology. Vol. 13, Technology and Feminism. Greenwich, Conn.: JAI Press, 1993. 31-42.