While in graduate school during the 2000s, I devised an independent study focused on my growing interest in the relationship between women and cars. What follows is one of the response papers in which I examine how – in the years following World War II – automotive style was reconfigured from a feminine trait to one that suggested masculinity and male power.

As the originator of the utilitarian, mass-produced automobile, Henry Ford had little respect for style. Ford believed the ultimate value of the motorcar rested in its reputation as a safe, efficient, and reliable mode of transportation. The car’s outward appearance, in Ford’s estimation, was of little consequence. History suggests that Ford was a rather narrow-minded man, and as such, adhered to racial, ethnic, and gendered stereotypes. His opposition to automotive style, therefore, was based not only on the belief that the car was defined primarily by functionality, but also because beauty and design were considered feminine characteristics, and should have no association with masculine automotive technology. In Ford’s “manly, efficiency-obsessed world of work,” concern for beauty was not only unwelcome, but was an indication of gender deviance (Gartman). Ford’s long-standing estrangement with his only child, Edsel, was often attributed to the elder’s intolerance of his son’s artistic leanings and suspected unmanliness. Like the “tough guys” who followed him, Ford believed “beauty belonged in the parlor and questioned the masculinity of any man who tried to put it on a car” (Gartman).

The emphasis on car design rather than function was the brainchild of one of Henry Ford’s staunchest competitors. Rather than work on improving automotive technology, which was a rather costly proposition, General Motor’s Alfred Sloan concentrated on “aesthetic innovation ” (Gartman). By changing the cosmetic appearance of the car, Sloan could offer the public a wider variety of styles and models without considerable financial investment. While this proposition made sound business sense, the association of auto design with femininity presented a considerable obstacle. Auto historians offer a number of factors that contributed to the eventual acceptance of the stylish and beautiful automobile. However, there was no greater influence than that of the flamboyant and charismatic automotive designer Harvey Earl.

Earl called upon both his larger-than-life personality and his personal design philosophy to change the way consumers felt about automobile design. While Earl has been described as a “dandy” in both dress and mannerisms, he overcompensated for such characteristics by cultivating a rather crude and super-masculine demeanor. Earl personally embodied both the stylish and the masculine through his large, impeccably attired frame, off-color language, and overbearing personality. In many ways, Earl was the ultimate personification of the automobiles he designed.

Social changes also contributed to the acceptance of automobile styling and its feminine associations. As former GM designer Leonard Pilato attests, “it is hard to separate auto design from human and social factors.” Auto historian Gartman suggests the gendered division between beauty and utility was breaking down during this time, as “men subjected to the savage utility and efficiency of mass production were looking to the home and its non utilitarian consumer goods for compensation.” Earl’s automotive designs, inspired by images of fantasy and flight, provided drivers with modes of entertainment and escape. While style may have been considered feminine, the forms on which Earl based his designs, which conjured up images of jet planes, speed and futuristic spacecraft, were examples of masculine technology and ideals. The emphasis on style rather than function also created new cultural meanings for automobiles. Rather than modes of transportation, cars became symbols of status, success, and power. The image, rather than the technology, of the car provided its owner with a new identity. As Gartman writes, the increased size of cars offered consumers “psychic compensation […] to convince them that their lives were indeed better.”

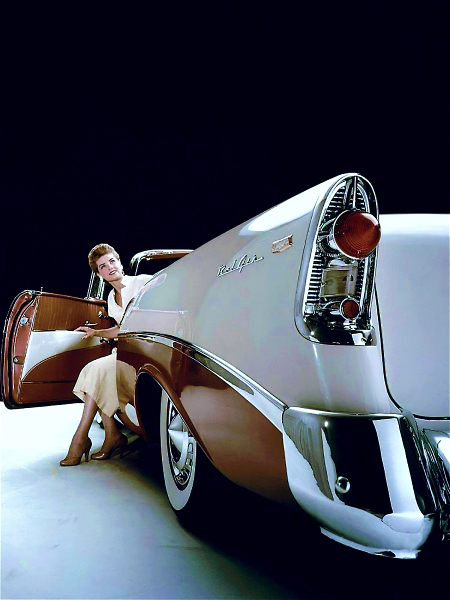

Auto historians often maintain that auto design became embraced once it became distanced from femininity. However, I would argue that beautiful cars became desirable because they were, in fact, regarded as female. The cars of the post World War II era were extremely feminine in appearance. The smooth curves and softened angles are reminiscent of women’s bodies. The pastel tones of 1950s automobiles are mirrored in the clothing of 1950s women. Many of the cars of this period are exceptionally “pretty” by today’s standards. The pink 1956 Thunderbird and lime green 1954 Corvette on display at the Henry Ford are extremely feminine cars that men often coveted. While men are known to drive particular cars to lure the opposite sex, they also seek to acquire mastery over the cars they drive. In a patriarchy, men seek to maintain power and control over women. If an automobile is considered female, power over the car may equate power over women. This equation had special significance to many men in the years following World War II.

After returning from the Second World War, men often discovered that the women they left behind were infused with independence and self-sufficiency, garnered through well-paying war time work. Uncomfortable with women’s developing autonomy, men took back the work in the public sphere and sent the women home. Husbands and fathers sought to regain the dominance of the prewar years as breadwinners and heads of households. They sought to purchase cars that symbolized this reassumed status. The cars many drove were masculine in size yet feminine in appearance. They were often given feminine names and referred to as “she.” The stylish car becomes the beautiful woman men conquer by owning and driving. As Gartman writes, “in the ultra-macho subculture of auto designers, sex was surely an important appeal.” Sex and the automobile have become intertwined not only because the automobile is a site of sexual encounter, but also because the car is often perceived as a spirited woman that male drivers seek to tame.

Men with style, especially white men, have always been sexually suspect. Equating stylish cars with beautiful women allows men to appreciate automotive design while keeping masculinity intact. Harvey Earl was instrumental in making style an integral part of the auto manufacturing process, and was influential in the acceptance of the importance of auto design. It is unfortunate that the equation of stylish cars as beautiful women to be controlled and conquered remains a mode of such acceptance for so many drivers.

Gartman, David. “A History of Scholarship on American Automobile Design.” Automobile in American Life and Society. University of Michigan Dearborn.

Gartman, David. “Tough Guys and Pretty Boys: The Cultural Antagonisms of Engineering and Aesthetics in Automotive History.” Automobile in American Life and Society University of Michigan Dearborn.

Pilato, Leonard. Lecture at the Henry Ford.