Being the ‘first’ in any endeavor represents a breakthrough moment – someone or something has crossed a boundary that had not been crossed before. The celebration of firsts suggests possibilities – something that was once considered impossible or off-limits can now be achieved. However, acknowledgement as a groundbreaker also carries the weight of expectations. An individual’s success or failure can influence how others in the same role or field are perceived. While this phenomenon exists in all fields of endeavor, it especially relevant for those whose “firsts” challenge existing power structures and societal norms. Although attention to female automotive firsts may diminish the achievements of those who follow, the determination and tenacity of women who were able to succeed in a culture in which they were not welcomed should not be disregarded. As Nanette Braun, of the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women, exclaims, “as long as women face barriers, it’s important to celebrate first-time achievements to show other women that such accomplishments are possible” (qtd in Morgan).

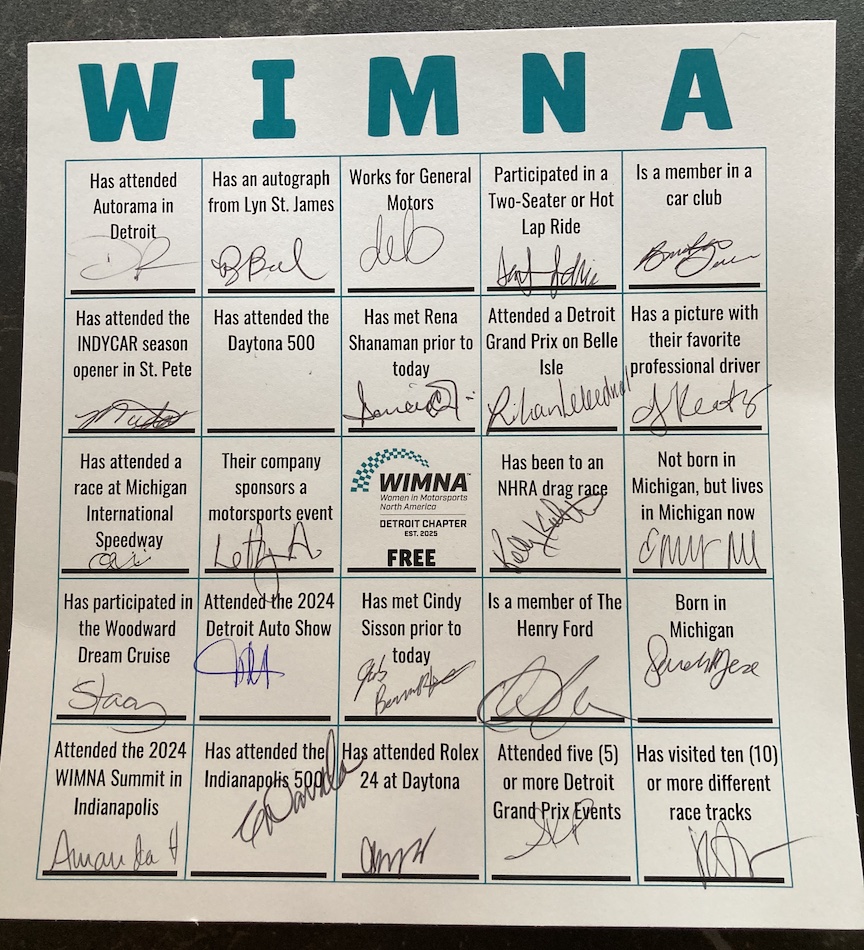

It is not surprising, therefore, that in automotive history, many of the celebrated women are ‘firsts.’ Bertha Benz was the first person, man or woman, to engage in a long-distance, internal-combustion-engine, automobile trip. Alice Ramsey was the first woman to drive across the US in an automobile. The ‘first female star of motorsports’ was a title bestowed on Joan Newton Cuneo for her racing acumen. Other female racers have also been honored as firsts – Louise Smith is regarded as the ‘first lady of racing;’ Betty Skelton was known as the ‘first lady of firsts.’ Janet Guthrie was the first woman to qualify at Indianapolis; Lyn St James was the first woman to be awarded the Indy 500 Rookie of the Year. Not only was Sarah Fisher the first woman drive for her own team, but was the first female owner to earn an IndyCar victory. The first woman to win an IndyCar race was Danica Patrick. Due to her record breaking accomplishments, Shirley Muldowney is often referred to as the ‘First Lady of Drag Racing.’ The three Force sisters – Ashley, Brittany, and Courtney, hold a collection of drag racing firsts. Other firsts include Nellie Goins, the first African American woman to succeed in Funny Car racing, and Cheryl Linn Glass, the first Black woman to race professionally.

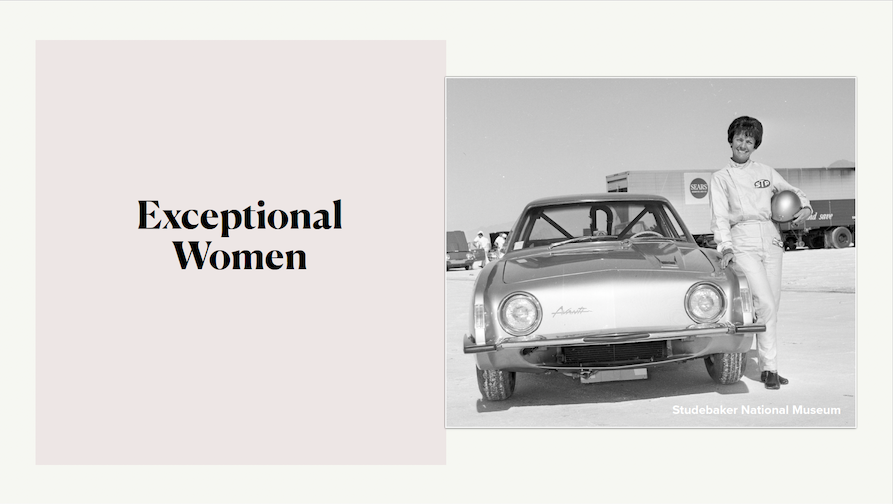

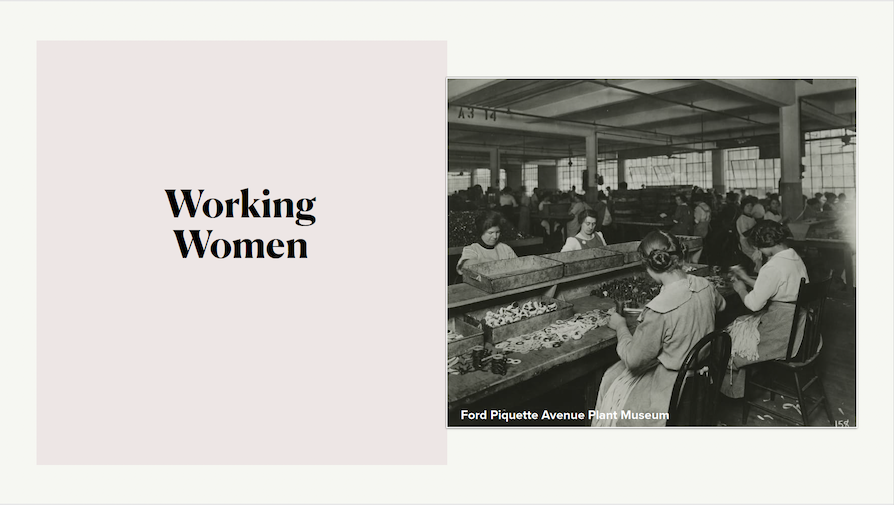

Female firsts are also noted in the auto industry. Helene Rother was the first woman to enter the field of automotive interior design at General Motors. Audrey Hodges Moore is recognized as the first full-time designer at an automotive company. The first female industrial designer at Studebaker was Helen Dryden. Betty Thatcher Oros was the first female exterior automotive designer on record. In more recent history, there is no more prominent ‘first’ than Mary Barra, the first woman to serve as CEO of a US automotive manufacturer. Whatever their automotive endeavor, these female firsts stood out as exceptional. They were women that through daring, perseverance, and a little bit of moxie, broke barriers and emerged victorious despite incredible odds. Exceptional women in history, notes Helen Antrobus, are those who lived and worked outside the stereotypical gender norms of the time. They are those “who subverted the conventional role of women, who shouted loud enough to be heard” (56).In automotive history, they are celebrated as pioneers, female heroes, and invaders of the male domain. They appear as long distance adventurers, auto industry interlopers, and motorsport legends.

However as a category of female success, the ‘exceptional woman’ both hinders and helps how women are considered in automotive history. The exceptional label can imply rarity rather than equality; it can suggest an individual’s accomplishments are unusual because of her gender, thus reinforcing the idea that success is the norm for men but not for women. It can give the impression that what a particular woman has accomplished cannot be easily duplicated by others; that she is, in fact, an anomaly, an outlier, a recipient of extraordinary circumstances, relationships, opportunities, coincidences, or luck. It can reinforce gender stereotypes, upholding the idea that women don’t belong in certain areas, and that those who succeed must be ‘special’ rather than talented or learned or skilled; any shortcomings can be generalized as evidence that ‘women aren’t suited’ for the role. It can be condescending, as though the person’s gender is more noteworthy than what she has accomplished. It can isolate rather than normalize, thereby slowing broader acceptance and inclusion.

However, the importance of female representation in automotive history cannot be underestimated. Research focusing on women’s participation within male-dominated environments repeatedly demonstrates how one woman’s success can serve as motivation and inspiration for those that follow (Lockwood et al). Asking “Do Female ‘Firsts’ Still Matter” in the US judicial system, Frick and Onwuachi-Willig note how the firsts of female judges all over the nation not only held important symbolic meaning for the advancement of women, but also “helped to change societal perceptions about who is and should be a judge” (1531). Female representation is considered crucial to the retention and recruitment of women in male-centric STEM fields. Write Drury et al, “female role models assist in both of these efforts by improving women’s performance and sense of belonging in STEM” (265). One of the barriers that perpetuates women’s exclusion from Formula One, argues O. Howe, is a lack of ‘representation and (in)visibility” (454). The younger generations need to “see it to be it,” Howe argues. “If a team were required to have a woman on their team, it could provide inspiration for the next generation of women race drivers […]” (460).

Research, notes Forbes contributor Margie Warrell, demonstrates that “role models have an amplified benefit for women due to the gender biases, institutional barriers and negative stereotypes women have long had to contend with across a wide swathe of professional domains.” As Warrell concurs, ‘”seeing is believing”. In terms of automotive history, attention to the firsts of exceptional women has the potential to inspire young women to think about a future as a designer, engineer, racer, owner, or even, perhaps, CEO.

Helen Antrobus. “Anonymous was a Woman: Collecting Cultures at the People’s History Museum.” Anonymous Was a Woman: A Museum and Feminist Reader, ed. Jenna C. Ashton (Cambridge: Museums Etc Limited).

Benjamin J. Drury, John Oliver Siy, and Sapna Cheryan. “Do Female Role Models Benefit Women? The Importance of Differentiating Recruitment From Retention in STEM.” Psychological Inquiry 22 2011, 265.

Amber Fricke & Angela Onwuachi-Willig. “Do Female ‘Firsts’ Still Matter? Why They Do for Female Judges of Color.” 2012 Michigan State Law Review, 1531.

Olivia Howe, “Hitting the Barriers – Women in Formula 1 and W Series Racing,” European Journal of Women’s Studies 20, no. 3 (2022): 454.

Penelope Lockwood et al. “To Do or Not to Do Using Positive and Negative Role Models to Harness Motivation.’ Social Cognition 22 (4) 2004: 422-450.

Gwen Morgan. “The Missing Story Behind Women’s First-Time Accomplishments.” Fastcompany.com Jan 1, 2017

Margie Warrell. “Seeing is Believing: Female Role Models Inspire Girls to Think Bigger.” Forbes.com Oct 9, 2020