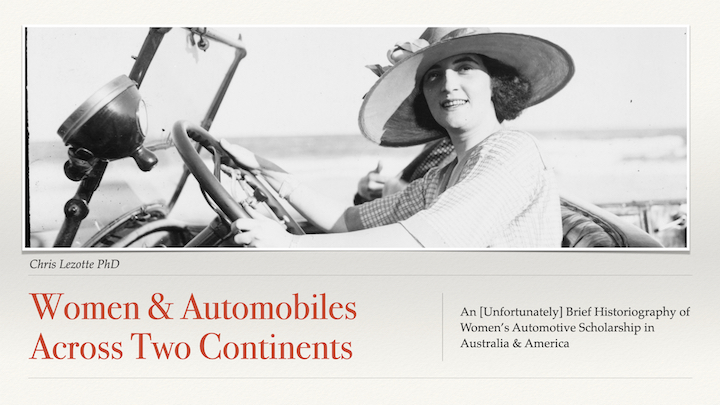

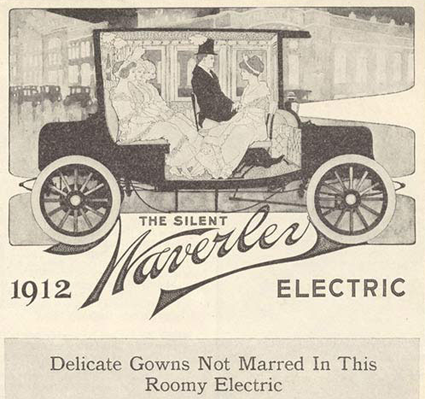

Since the beginning of the auto age, women’s driving has been subject to both restriction and ridicule. In the early twentieth century, when the gasoline-powered automobile made its debut, female motorists were purposefully and insistently directed toward the electric vehicle. While its cleanliness and ease of handling were promoted as perfect for the woman driver, the electric car’s lack of power and range assured that the lady behind the wheel never ventured too far from home. Such efforts to constrict women’s driving were based on the fear that the freedom and opportunity automobility promised would lead to the abandonment of women’s traditional gender roles.

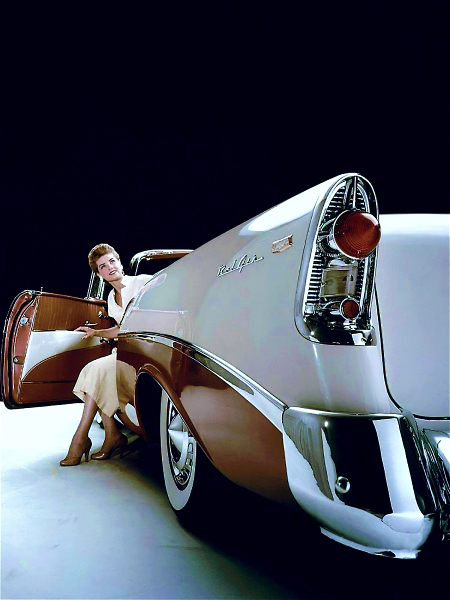

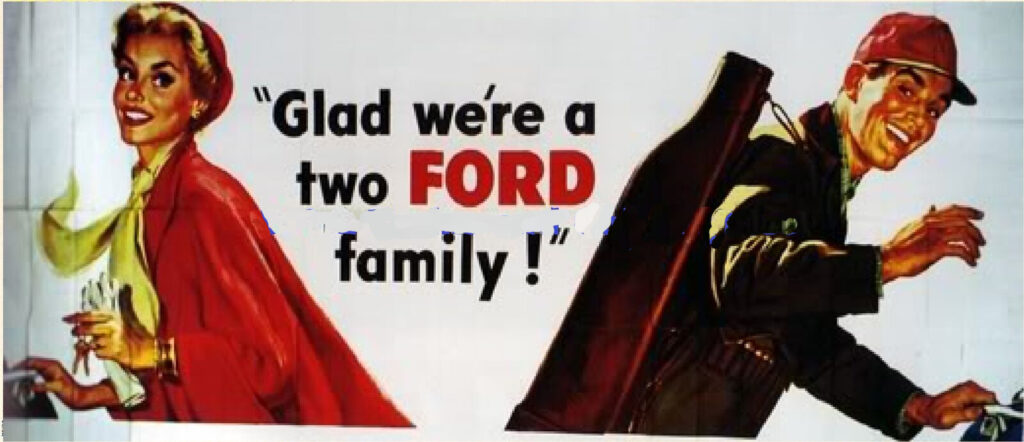

Once women dismissed the electric in favor of the faster, more powerful gasoline driven automobile, the female motorist became a subject of ridicule in the popular press. In an attempt to curtail and question women’s driving ability, the stereotype of women as too weak, nervous, mechanically inept, and distracted to safely and effectively handle an automobile was indelibly instituted into American folklore. As Michael Berger writes, ‘The development and support of a stereotype likely to limit the number of women on the road and the mileage they drove, together with the folklore that accompanied it, were reasonable developments from the perspective of those who sought to minimize the impact of the automobile as a vehicle for the liberation of women’ (259). A century later, women’s driving skills continue to be denigrated through the recirculation of women driver stereotypes. And women drivers continue to be directed toward safe, spacious, and reliable vehicles that fulfill the role of wife and mother rather than to the rugged, powerful, and performance driven vehicles typically marketed to men.

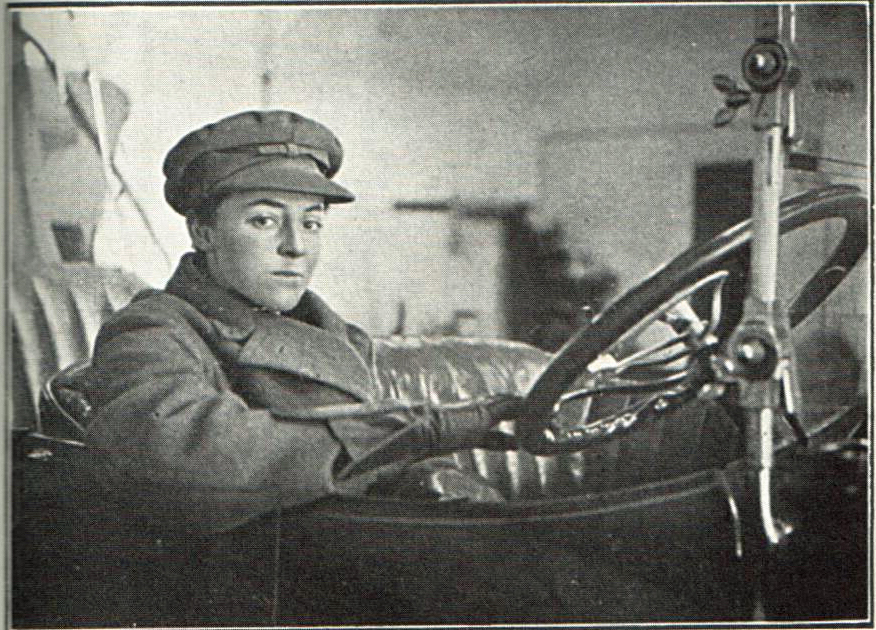

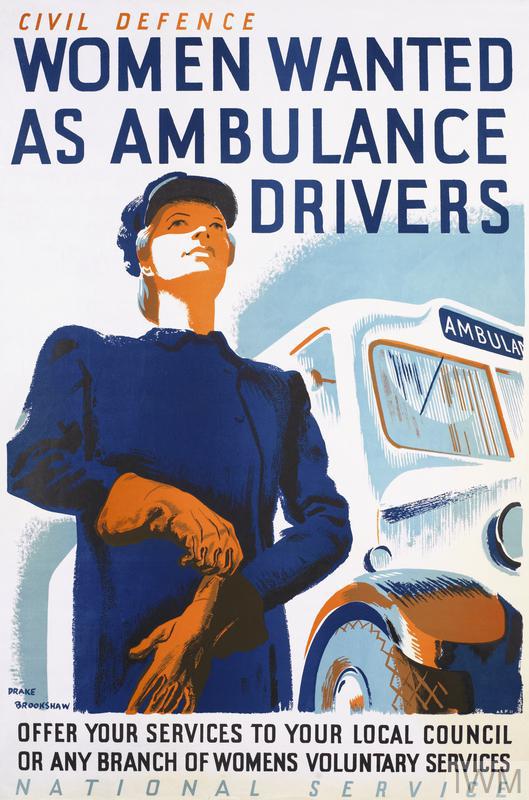

However, while efforts to constrain women to gender-appropriate vehicles continue well into the twenty-first century, there have been periods within the past 100 years in which such restrictions have been temporarily lifted. And that is during periods of war. During the two World Wars, women from the US and abroad were called on to take jobs not only in home town factories producing munitions, building ships, and airplanes, but also overseas as drivers of fire engines, trucks, buses, jeeps, and ambulances. They delivered medical supplies, transported patients to hospitals, and drove through artillery fire to retrieve the wounded. Suddenly, the weak, incapable, and timid women – as described in the ubiquitous stereotype – were deemed eminently suitable if not necessary to carry on the transportation needs of countries at war.

Women who could not only drive but also work on vehicles were especially valuable. Many mechanically-inclined women left domestic chores behind to serve their respective countries through the maintenance and repair of wartime trucks and jeeps. Perhaps the most famous of these volunteers was the late Queen Elizabeth II. Dubbed the ‘gearhead monarch’ by a few automotive writers, the young Princess ‘donned a uniform and learned not only how to drive heavy trucks for the war effort but also how to wrench on them’ (Strohl). At the age of 18, Elizabeth joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service, a branch of the British Army as a second subaltern, eventually earning a promotion to Junior Commander. She was, in fact, the first woman from the royal family to serve in the military. As part of her training, the young Elizabeth had to pass a driving test, learn to read maps, and take instruction in vehicle repair and maintenance. Dubbed ‘Princess Auto Mechanic’ by the British Press, Elizabeth took her military roll seriously, driving army ambulances and learning to repair heavy trucks on the battlefield. Her wartime experience led to a lifelong love of trucks [particularly Land Rovers] and driving; she reluctantly gave up driving public roads in 2019 at the sprite age of 93. [Here’s a video of the Queen behind the wheel on the royal estate.]

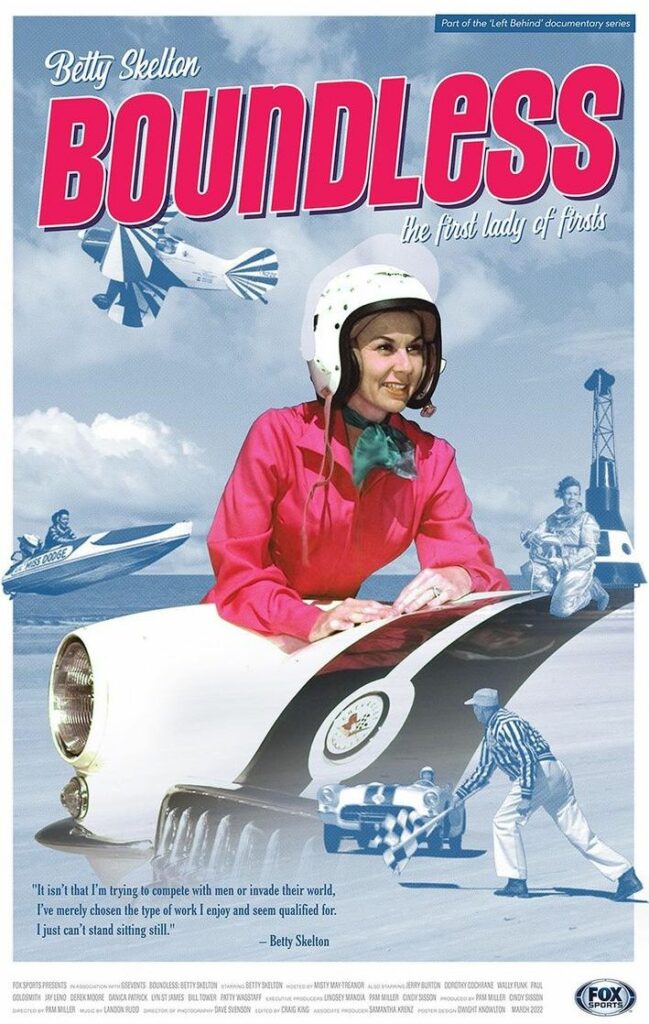

Although discouraged from engaging in men’s work after the war, there can be little doubt that many of those women who fulfilled similar wartime roles as the ‘Princess Auto Mechanic’ emerged with a sense of purpose as well as a newfound confidence in themselves and their capabilities. As historian Kathryn Atwood writes, ‘[…] most of these women – the famous and the obscure – had one thing in common: they did not think of themselves as heroes. They followed their consciences, saw something that needed to be done, and they did it.’ Despite a century of attempts by auto manufacturers, marketers, and the media to restrict and demean women’s driving, women have demonstrated time and time again that they are not only capable if not exceptional drivers, but when called upon can draw upon inherent mechanical and driving skills in the service of their countries as well as to serve and empower themselves.

Atwood, Kathryn. Women Heroes of World War II: 32 Stories of Espionage, Sabotage, Resistance, and Rescue. Chicago: Chicago Review Press (2019).

Berger, Michael. ‘Women Drivers!: The Emergence of Folklore and Stereotypic Opinions Concerning Feminine Automotive Behavior.’ Women’s Studies International Forum 9.3 (1986): 257-263.

Strohl, Daniel. ‘United Kingdom’s First Truck-Driving Queen Dies at 96.’ hemmings.com