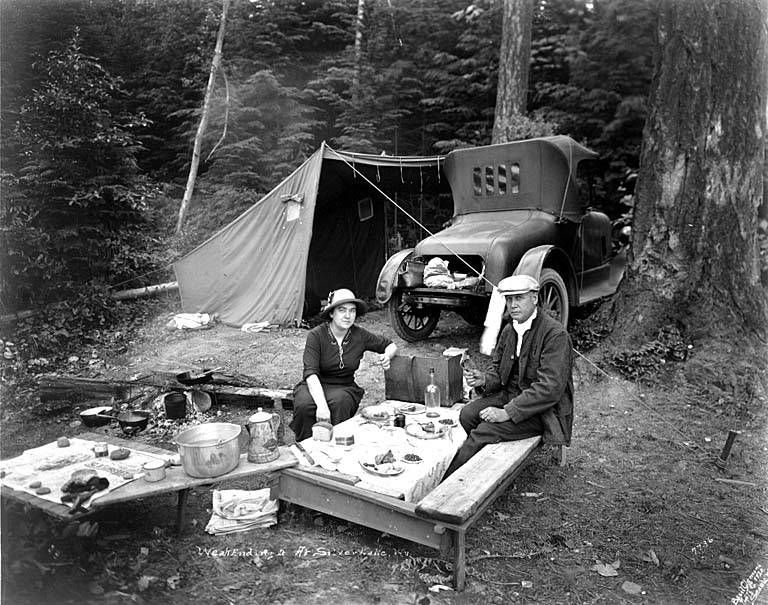

A recent Jalopnik article asked its readers to elaborate on how they ‘got into cars.’ While the responses included references to racing, car magazines, and movies, the majority fell into two categories. The first route to a life as an auto enthusiast was through a relationship with a male relative or mentor, most often one’s dad. The second was a childhood preoccupation with ‘toys that move,’ whether those vehicles were the popular Hot Wheels, Matchbox cars, model cars, slot cars, Tonka trucks, or racing sets. Although women compose over half of US licensed drivers, cars are very much perceived as a male interest. This was evident in the comments accompanying the Jalopnik article which were, as far as I could tell, posted overwhelmingly by men. This suggests that while women are engaged with the automobile as drivers, they are less likely than their male counterparts to take on the mantle of ‘auto aficionado.’ If the Jalopnik article does, in fact, reflect the most common routes to automotive interest, it would appear that such influences are absent in women’s early lives.

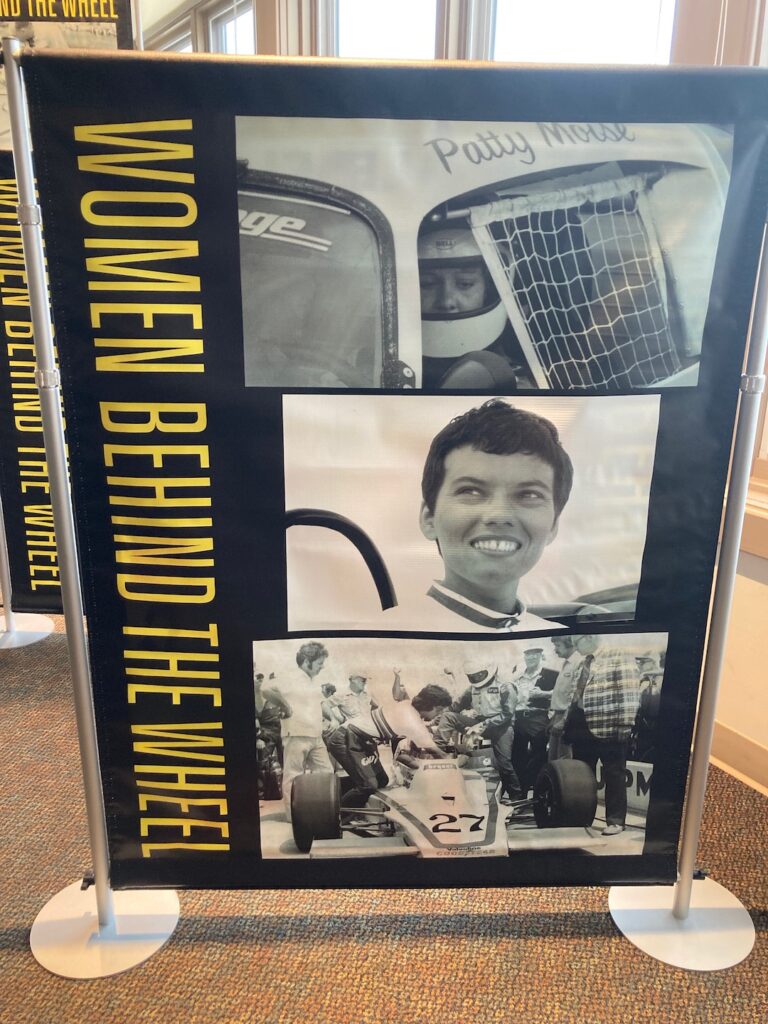

In my own research into women’s relationship with the car – particularly as participants in automotive cultures traditionally associated with the male driver [i.e. muscle cars, pickup trucks, and motorsports] – the encouragement of a male family member or mentor was instrumental in instigating and maintaining a girl’s or young woman’s automotive interest. Many of the women interviewed in these various projects noted the importance of fathers, boyfriends, and husbands in acquiring a love for all things automotive. It is significant to note that the majority who responded in this manner were without male siblings, which suggests that dad would not have had as much concern in encouraging his daughters if he had sons [one has to wonder if the Force sisters would have made such an impact on the drag racing world if John Force had a son or two.] A much smaller percentage of the women noted how they developed in interest in cars by ‘borrowing’ the matchbox cars of brothers or male playmates. Young girls are rarely gifted toy cars; toys that move have always been promoted as proper toys for boys. While the notion that ‘girls just aren’t interested in cars’ has become somewhat of a rationale for women’s general lack of participation in automotive culture and industry, the gendered division of playthings -particularly toy cars and trucks – has deprived girls from the likelhood of developing a passion for the automobile.

Toys often serve as introductions to and reinforcements of cultural and gender expectations. As among the earliest and most influential technologies with which children come into contact, toys ‘transmit to children […] particular views of gender relations, examples of appropriate behavior, and character models’ (Varney 2002, 153). The gendered demarcation of toys was well established by the early twentieth century. The transition from horse drawn carriages to gasoline-powered automobiles was reflected in the playthings available to young boys – horse and buggy toys were replaced by miniature cars. Young girls also experienced a gendered progression – the Victorian sewing doll was superseded by the baby doll. While baby dolls reinforced the expectation that women would live quiet and unassuming lives as mothers, ‘toy vehicles captured the variety of men’s life of automobility, as drivers of status cars, as deliverers of useful goods, as roadmakers, and race car drivers. These were male machines that opened up a dynamic modern world to their drivers’ (Cross 2009, 56). Much like the vehicles they imitated, toy cars were irrefutably associated with technological aptitude, risk taking behavior, and maleness. As Ruth Oldenziel (2001) suggests, ‘toys were intended not only to amuse and entertain but also as socializing mechanisms, as educational devices and as scaled-down versions of the realities of the larger adult-dominated social world’ (42).

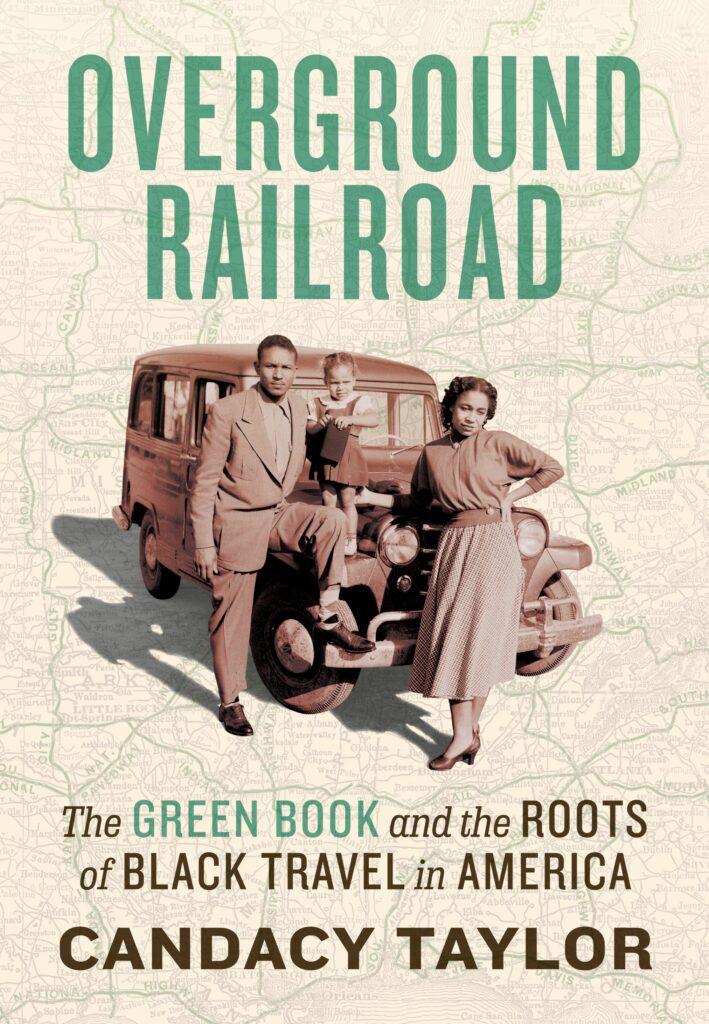

The lack of automotive exposure in childhood can have significant repercussions in adulthood. As I noted in an examination of women’s car advice websites (Lezotte 2014), without a grasp of automotive knowledge women are likely to experience significantly more discrimination in purchasing and servicing automobiles than their male counterparts. And without early exposure to cars, women are less likely to consider careers in auto-related industries or professions. Links between machinery and masculinity, originating in the assignment of mechanical toys to boys, has kept particular skills and professions within male domination. ‘In a society which thinks highly of technology and which there is an elaborate relationship between power and technology,’ notes Wendy Varney (2002), ‘this exclusion from that domain can effectively lock one out of a vast area of influence’ (168). Not only does this lack of auto interest and education limit women’s occupational opportunities, but can lead to a scenario in which decisions in vehicle engineering, design, production, and use are left primarily to the men in charge. As Wheel writer Emily Fritz (2018) asserts, ‘As we neglect to involve girls in car culture from a young age, we are also neglecting to involve them in the opportunity to learn and gain skills such as the ability to use tools, the ability to formulate basic civil engineering, and the ability to come in contact with the ways in which moving parts work—all of which are found in many car-based boy’s toys.’

The Jalopnik article – and the overwhelmingly male responses – is not only indicative of what is certainly a mostly male readership, but also demonstrates the importance of toys that move in the development of automotive interest in young boys. Since the majority of young girls grow up to be drivers, it is puzzling [but not surprising] that they are dissuaded from engaging with cars at the age in which they are most impressionable. But then again, most boys grow up to be fathers, yet are discouraged, if not ostracized, when demonstrating any interest in dolls. Such is the gendered power of toys.

Note: some of this material is taken from an article-in-progress on the Barbie car.

Cross, Gary S. 2009. Toys and the Changing World of American Childhood.

DaSilva, Steve. 2022. ‘These Are the Stories of How You Got Into Cars.’ Jalopnik 10 Oct.

Fritz, Emily. 2018. “The Harm of Gender Roles in Car Culture: An Argument for Getting Girls Involved.” Wheel.

Lezotte, Chris. 2014. ‘Women Auto Know: Automotive Knowledge, Auto Activism, and Women’s Online Car Advice.’ Feminist Media Studies.

Oldenziel, Ruth. 2001. ‘Boys and Their Toys: The Fisher Body Craftsman’s Guild, 1930-1968, and the Making of a Male Technical Domain.’ In Boys and Their Toys: Masculinity, Class and Technology in America, edited by Roger Horowitz, 139-168.

Varney, Wendy. 2002. ‘Of Men and Machines: Images of Masculinities in Boys’ Toys.’ Feminist Studies 28(1): 153-174.