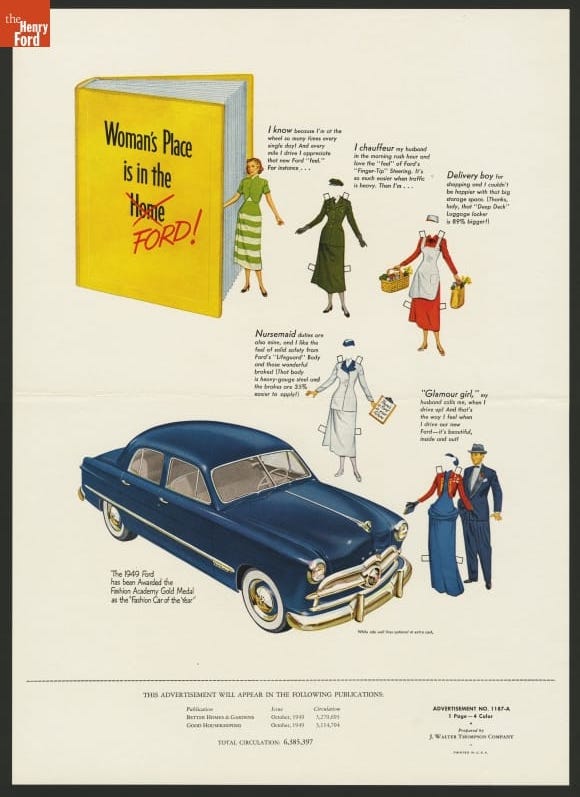

In the short time I spent at a Detroit automotive advertising agency, I became acutely aware of how men’s ideas of women’s automotive interest overruled any consideration of what women actually desired in a car. The women who worked in automotive advertising, as well as the women who were the target of automotive advertisers, were routinely considered lacking in automotive knowledge, unfamiliar with the driving experience, and subject to the influence of male automotive “experts.” It was assumed that the female consumer would buy the vehicles the male-dominated auto industry deemed suitable for the woman driver, and it was believed that the woman in the creative process would rely on male-directed research rather than her own car experience. George Green, a retired advertising executive who worked on the General Motors account, admits that automakers routinely “denigrated the female market,” and made little effort to learn about the woman car buyer (qtd. in Gerl & Davis 210).

Admittedly, the notion that the auto industry was complicit in the intentional disregard of women’s automotive interest was based on my own agency experience rather than any established research. While automobile advertising has been analyzed as a text – i.e. what it symbolizes, what it means, what it says about the woman driver – how that advertising came to be had never, to my knowledge, been addressed in scholarship. Until now.

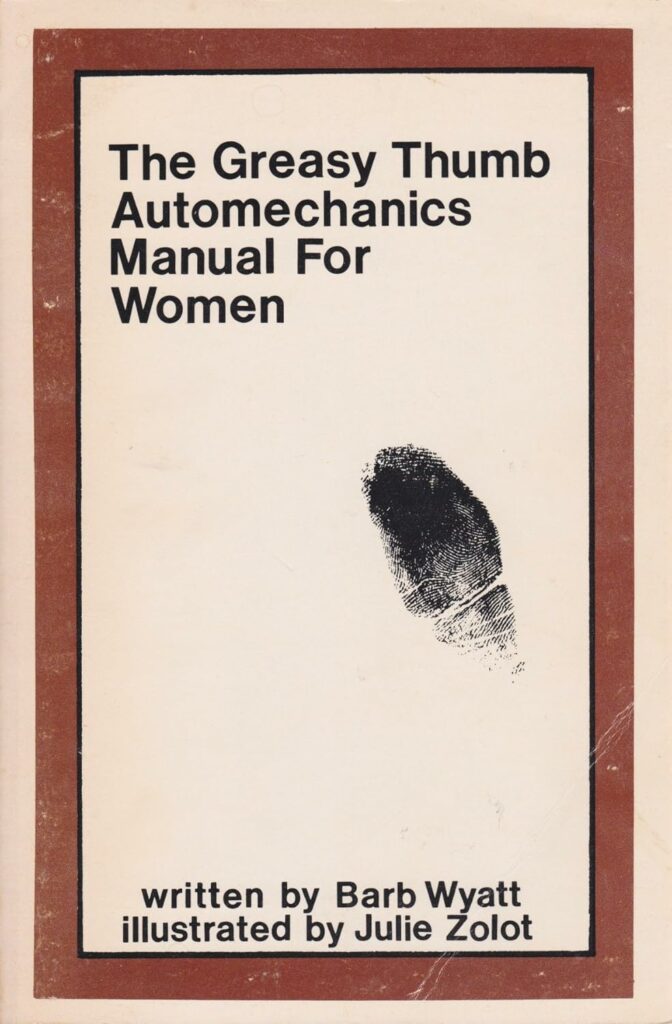

In Pink Cars and Pocketbooks, historian Jessica Brockmole uncovers the multiple market studies focused on the female consumer that were overlooked and under-appreciated by the automotive industry for nearly half a century. Through her investigation into decades of advertising archives, trade journals, women’s magazines, and newspapers, Brockmole chronicles how women, dissatisfied and discouraged with how they had been repeatedly misrepresented by automotive marketers and decision makers, took it upon themselves to become more informed, experienced, and knowledgeable about cars. She relates how through the formation of women-centered car clubs, driving handbooks, and do-it-yourself repair manuals, these women ‘bought their way’ into the masculine car culture and became empowered consumers and drivers. As the author declares, because of the unwavering efforts of a determined group of female consumers, “[women] no longer have to rely on the auto industry to decide what and how much they can know about cars. They no longer have to accept how the auto industry limits their relationship with cars or defines who and what a ‘woman driver’ is” (205).

Pink Cars and Pocketbooks offers an unusual, resourceful, and never-before-told history of women’s relationship with cars. In this painstakingly researched and engagingly written work of historical scholarship, Brockmole uncovers how savvy female consumers, through the sharing of automotive knowledge, challenged gender prescriptions and took control of their own automotive futures.

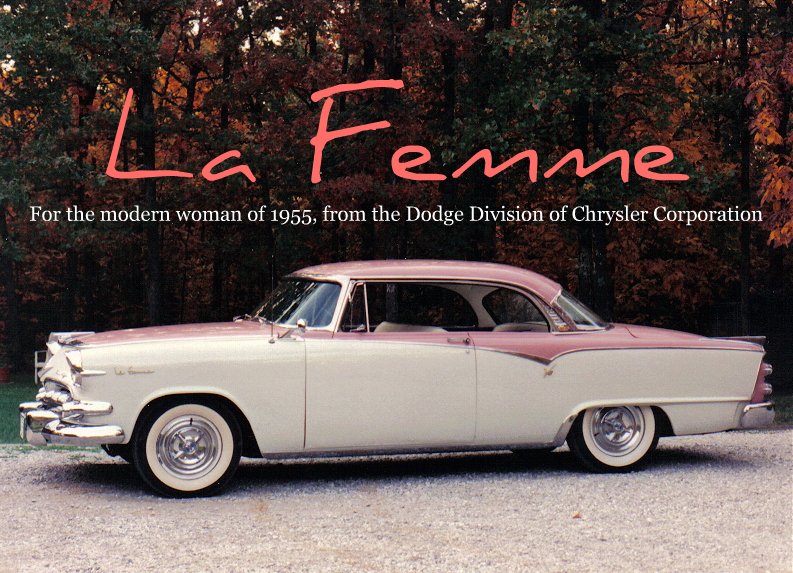

If you’ve ever wondered how automakers so utterly misread women with the introduction of the Dodge La Femme, I heartily encourage you to read this book!

Brockmole, Jessica A. Pink Cars and Pocketbooks: How American Women Bought Their Way into the Driver’s Seat. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2025.

Gerl, Ellen J. and Craig L. Davis. “Selling Detroit on Women: ‘Woman’s Day’ and Auto Advertising, 1964-82.” Journalism History 38.4 (2013): 209-220.