One of my tasks after joining the Society of Automotive Historians was to form a relationship with a university with an automotive presence. The objective was to share knowledge and resources; the SAH hoped to establish a home base with a renowned Michigan based research institution to both store and share its considerable publications, records, and archives. After investigating a number of possibilities, a partnership was formed with Kettering University in Flint, Michigan. Kettering, formerly known as the General Motors Institute [GMI], prides itself as one of the country’s premier STEM institutions, ‘known around the world for educating great and successful leaders, entrepreneurs, innovators, engineers, scientists, and business people.’ In return for the storage of its archives, the SAH proposed a number of educational opportunities for Kettering University students, which included funding a travel grant to conduct research at the Kettering Archives.

The first SAH/Kettering Travel-to-Collections Grant was awarded earlier this year to Jennifer Eaglin, PhD, an associate professor of history at Ohio State University. A native of Ann Arbor, Dr. Eaglin’s interest in cars came through her father. As she noted, it is hard to be from Michigan without some automotive connection. Dr. Eaglin used the grant to conduct further research for a current book project – ‘Auto Americas: An Hemispheric History of the Automobile.’ After a week at the Kettering Archives, Dr. Eaglin presented her research to a group of Kettering faculty, students, staff, and interested guests. Two SAH members, myself included, made the trip to Flint for the presentation.

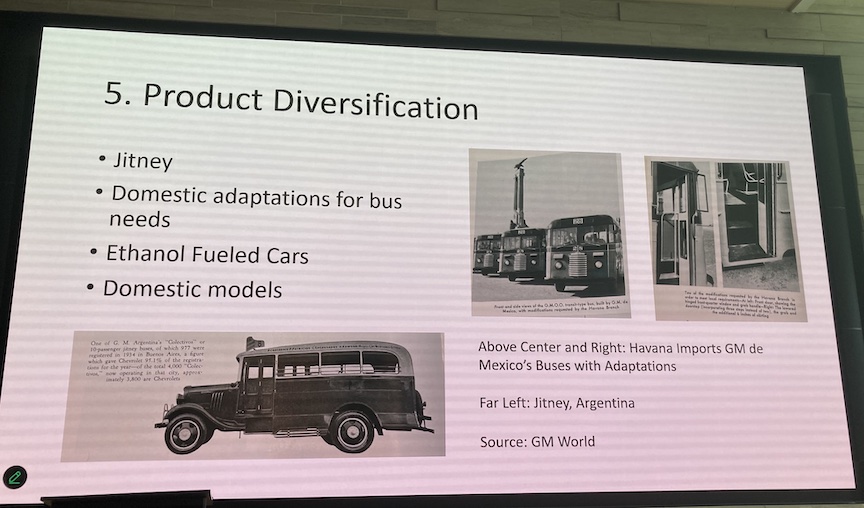

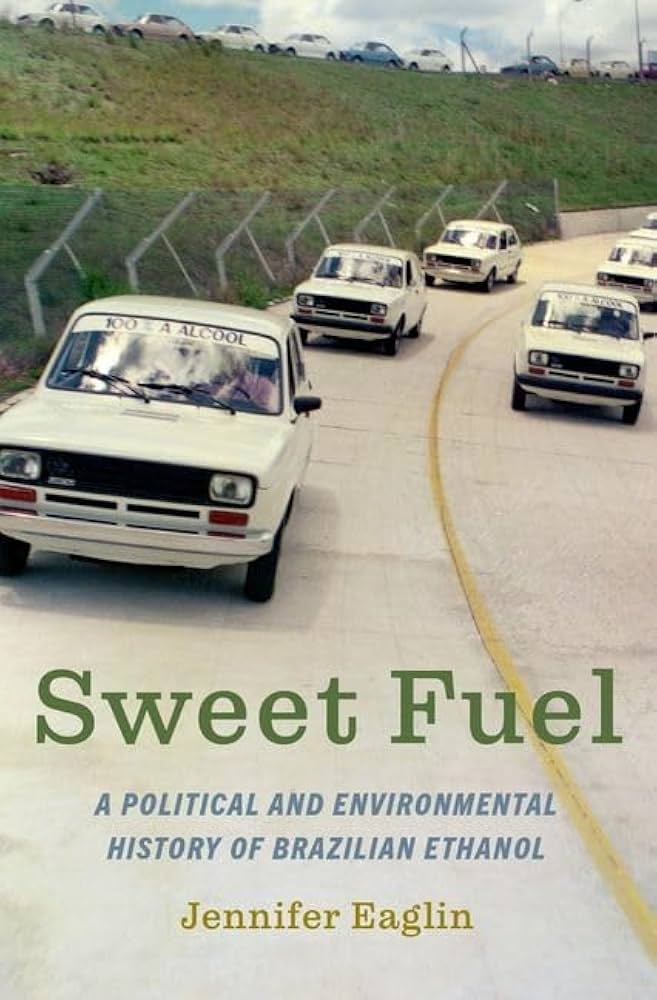

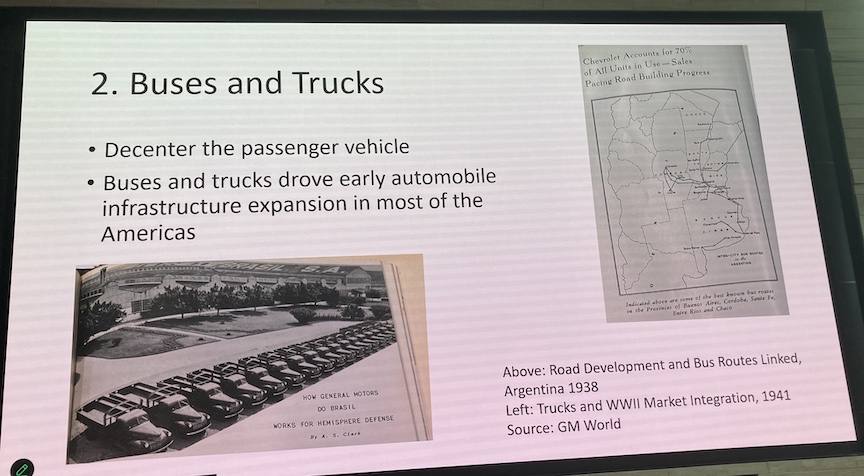

Dr. Eaglin’s past projects include her first book which focused on ethanol as a source of alternative energy for Brazilian automobiles. Eaglin’s body of work moves beyond the United States to consider automobility as a collective Western hemisphere experience to incorporate all the Americas. Her research questions for this particular project include what makes the American experience collective; how did the auto industry expand in similar ways across the Americas; how did these experiences differ; how does understanding this this process explain the Western Hemisphere’s continued disproportionately heavy dependence on automobiles in the 21st century compared to the rest of the world. While United States automobility is centered primarily on cars, Eaglin’s more expansive approach changes the focus to more universal modes of transportation such as buses and trucks.

As someone who is interested in the woman-car connection, I was especially thrilled to see that a female scholar was the initial SAH/Ketttering Travel to Collections Grant recipient [although I had nothing to do with the selection]. Although Dr Eaglin’s work is not focused on gender in any way, it is encouraging to have someone in her position conduct research that focuses on the automobile. For generations, the field of automotive history has been dominated by male scholars. As an individual who not only researches but teaches automotive history, perhaps Dr. Eaglin will inspire a new generation of scholars – young women and men – to further the practice of automotive history research.