While there have been many histories devoted to the automobile since it first appeared on the American scene in the early twentieth century, very few pay particular attention to women’s automotive involvement or interest. This absence is not only evident in the thousands of publications devoted to automotive history, but in locations such as the automotive museum as well. My newest project examines the representation of the woman driver in a dozen or so automotive museums. It will consider how each museum positions the role of women in automotive history, the methods by which women’s automotive involvement and impact is displayed, how women’s position in automotive history is regarded in comparison to that of men, and perhaps offer suggestions as to how museums might better address the role and influence of women in automotive history and American culture. While most of the museums I plan to visit are located in southeastern Michigan and neighboring states, I took the opportunity to stop by the AACA Museum in Hershey, Pennsylvania while in town for meetings and events of the Society of Automotive Historians.

The AACA Museum was originally conceived as an ‘automobile collector’s’ museum. While the museum has expanded to include both permanent and special exhibits, its foundation as a holding place for collected automobiles is evident. Many of the automobiles are accompanied by a placard which provides information about the car as well as the donor. Included are the specifications of the automobile as well as personal stories about how the car was obtained and used. As I walked through the building, I noted that there were a few cars donated or previously owned by women. These included a Berkshire green and white 1961 Nash, with a “Patti’s Met” front license plate, a 1940 Mercury handed down from father to daughter, and a 1935 White built especially for a prominent female Boston ophthalmologist.

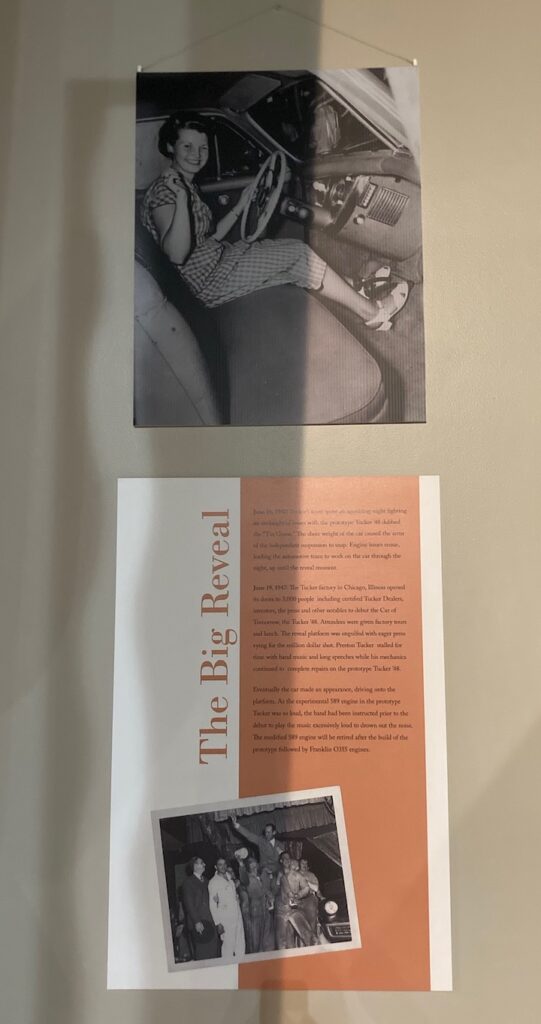

While female mannequins were featured in some of the displays, and photographs that pictured women in or around historical automobiles were placed in a few of the exhibits, how women used the automobile or women’s influence in automotive history was not addressed. Some of this has to do with the nature of the museum – the exhibits were often constructed around the donated automobiles in the collection. However, someone visiting the museum could easily get the impression that women were not, in fact, a part of automotive history at all. The absence of women reinforces the notion that automobiles and automotive history are a strictly masculine enterprise.

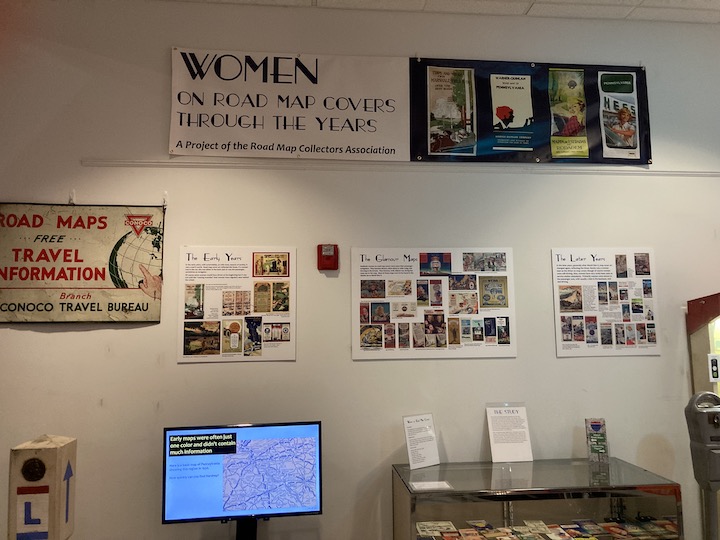

There was one exhibit – tucked away in a corner – that included a small section devoted to the role of “Women on Road Maps.” This was part of a special exhibit earlier in the year that was transferred to the permanent road map display. As the press from the April event reads, the display highlights “how women were portrayed on map covers through the 20th century. As motoring became more accessible and popular with women and families, women were portrayed sometimes as navigators, sometimes drivers, sometimes in glamorous style, and sometimes as moms. We salute the role of women in motoring and the artistic renderings gracing map covers and travel promotion.” While the information on the map collection was interesting and informative, with full-color samples of the representative map covers, the signage was placed so high above the main display it was nearly impossible to read. It is unfortunate that the only display to address women’s automotive history in any fashion was hidden in a corner and inaccessible to all but the most determined museum visitor.

This first stop on the museum project – the AACA Museum in Hershey – was not only a nice break from the myriad of SAH activities, but further convinced me that women’s representation in automotive museums is a topic very much worth investigating.