There is nothing subtle about the Stahl Museum. Located in an industrial park in Chesterfield, Michigan, it is a voluminous, warehouse-type space jammed packed not only with vehicles, but also period organs, juke boxes, gas station paraphernalia, neon signs, and automotive artifacts stuffed every available nook and cranny. Automotive advertisements hang from the rafters, and organ music blares from any one of the ornate instruments situated along the perimeter. As a personal collection of Ted Stahl, the museum reflects the interests and particular proclivities of its owner. As noted on the museum website, Stahl’s mission for the collection is ‘to build an appreciation for history;’ that of his wife Mary is ‘to see the smiles on the faces of our visitors.’

The museum is only open to the public Tuesday afternoons and the first Saturday of each month. Not surprisingly, it was quite crowded when I visited on a pleasant day in early April. Parents maneuvered small children through aisles of tightly packed cars while grey-haired guides answered questions and offered historical background. Younger volunteers cheerly took organ tune requests from the public. The atmosphere in Stahl’s can only be described as carnival like, a ‘fun house’ of a museum as it were. More than a mere collection of cars, Stahl’s refers to itself as ‘An American Auto Experience.’

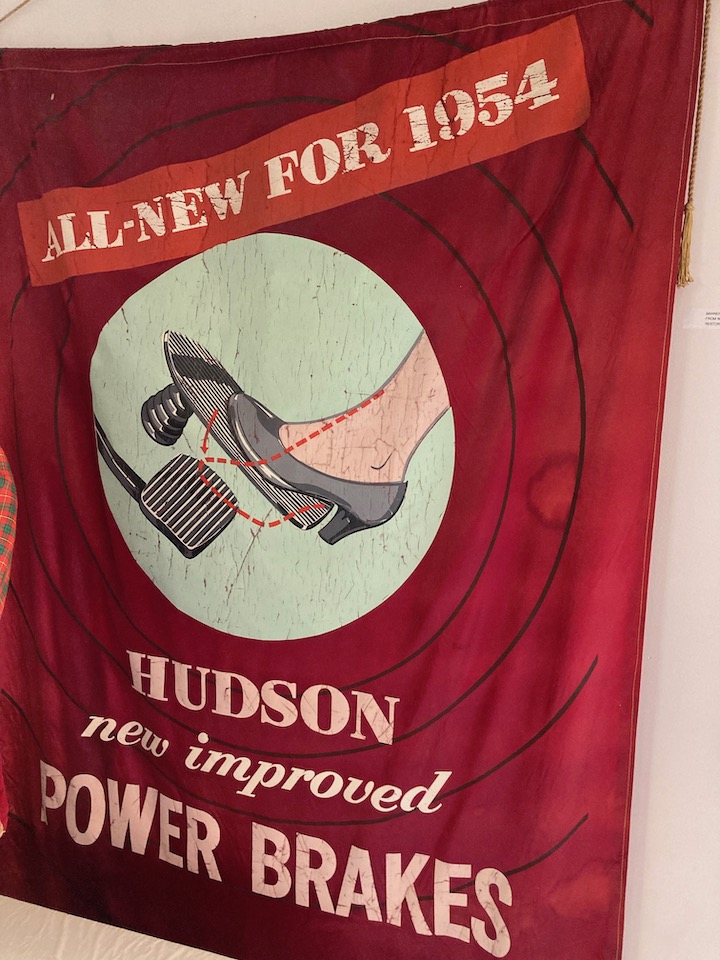

That being said, Stahl’s car collection is quite impressive. It leans toward the vintage and brass eras, which no doubt reflects the owner’s predilection to bright, shiny, and over-the-top objects. Many of the cars display signage from past Concours shows, which, to the auto aficionado, serves as an indication of automotive importance and value. Stahl’s prides itself on its accumulation of ‘some of the world’s most rare and distinctive cars’ and ‘treasures from the past you won’t find anywhere else.’ The gigantic and fantastic music machines that boisterously fill the halls; the ornamented and embellished brass cars that reflect images of all who pass; the flashing roadside signage that cover the walls and hang from the ceiling; the outrageous movie cars in period displays; and the 50s automobiles parked around a drive in diner all contribute to a unique and often overwhelming experience.

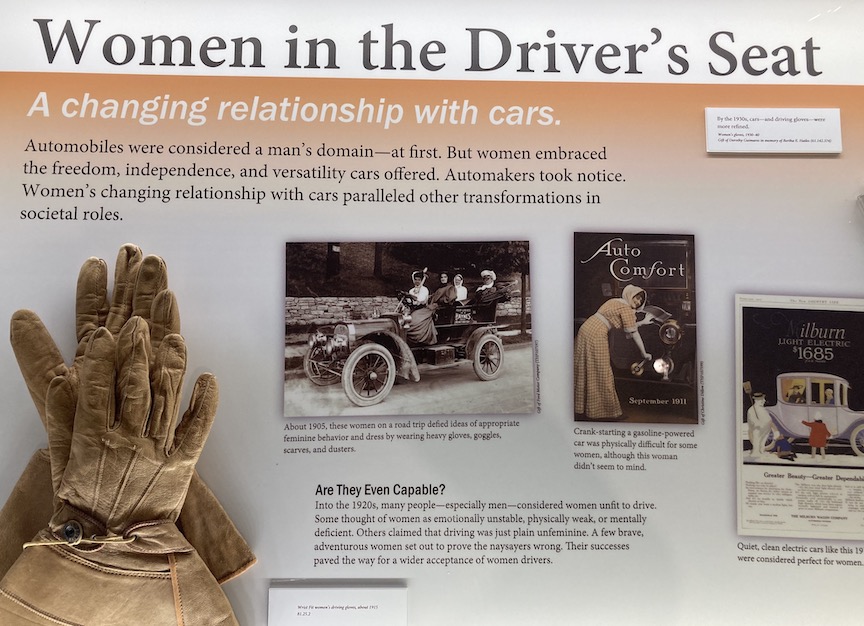

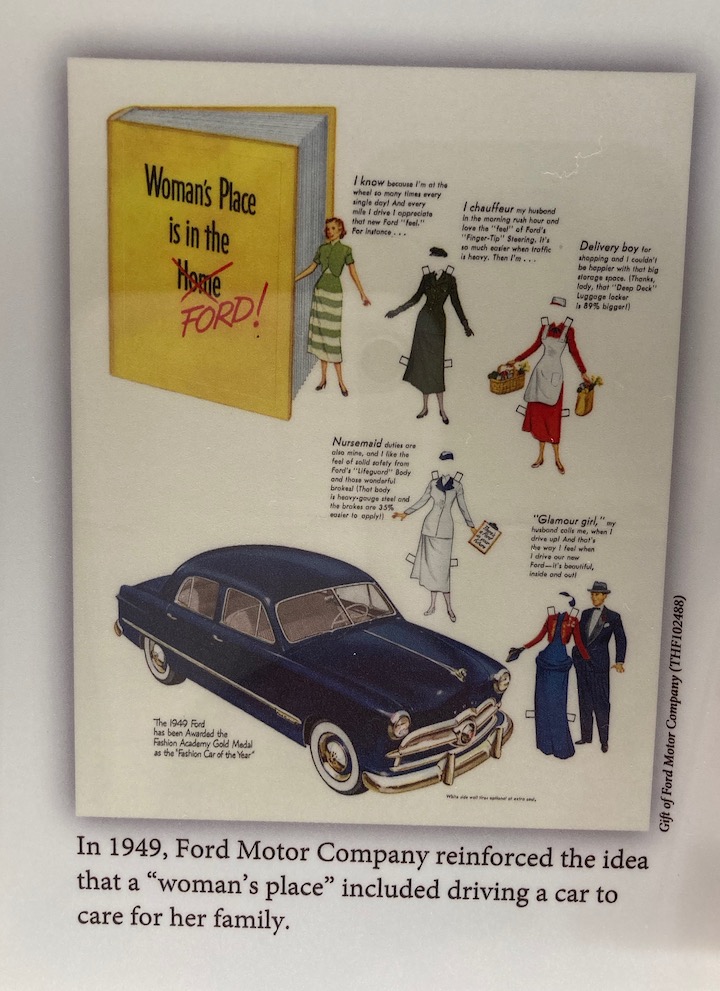

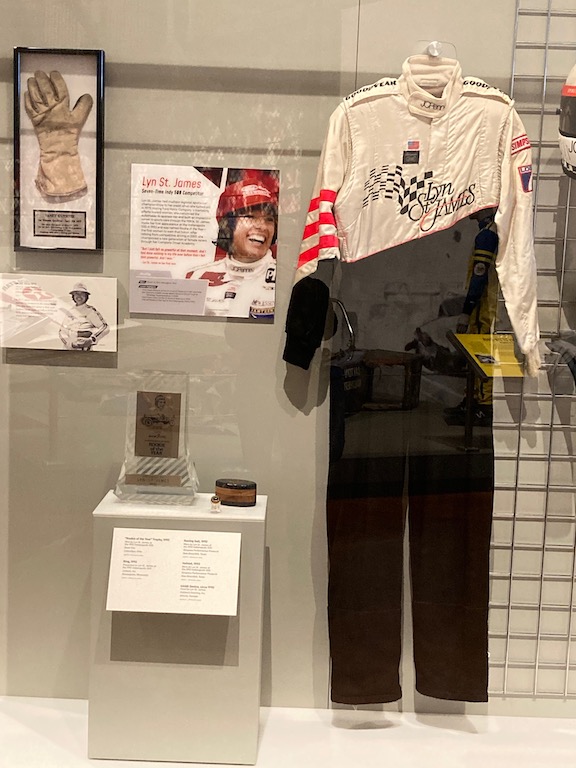

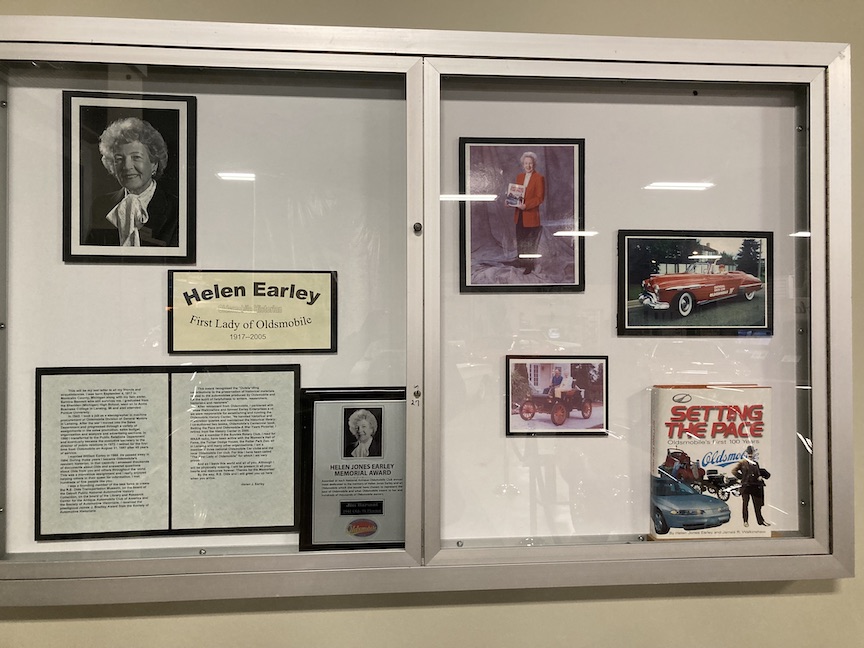

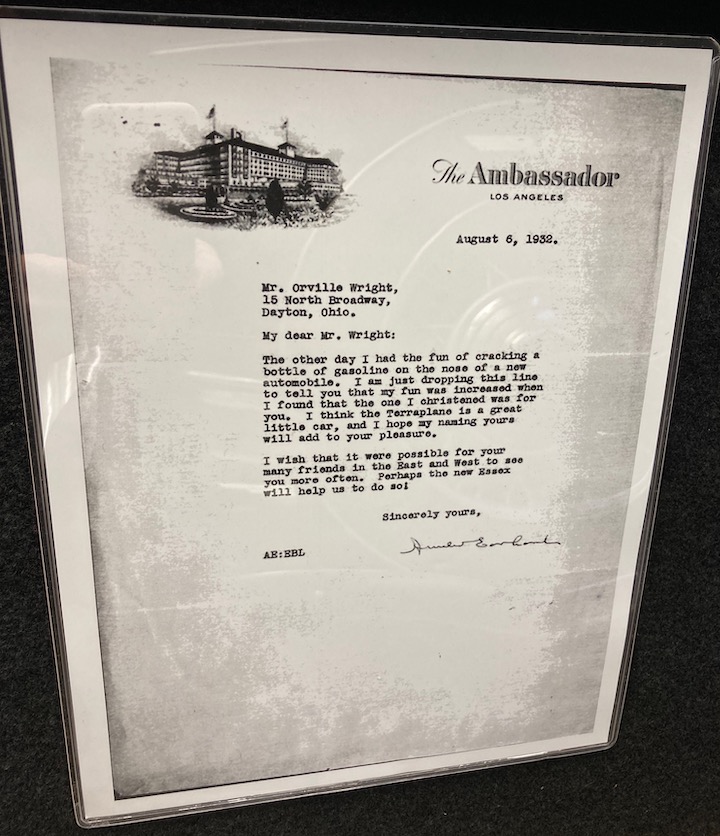

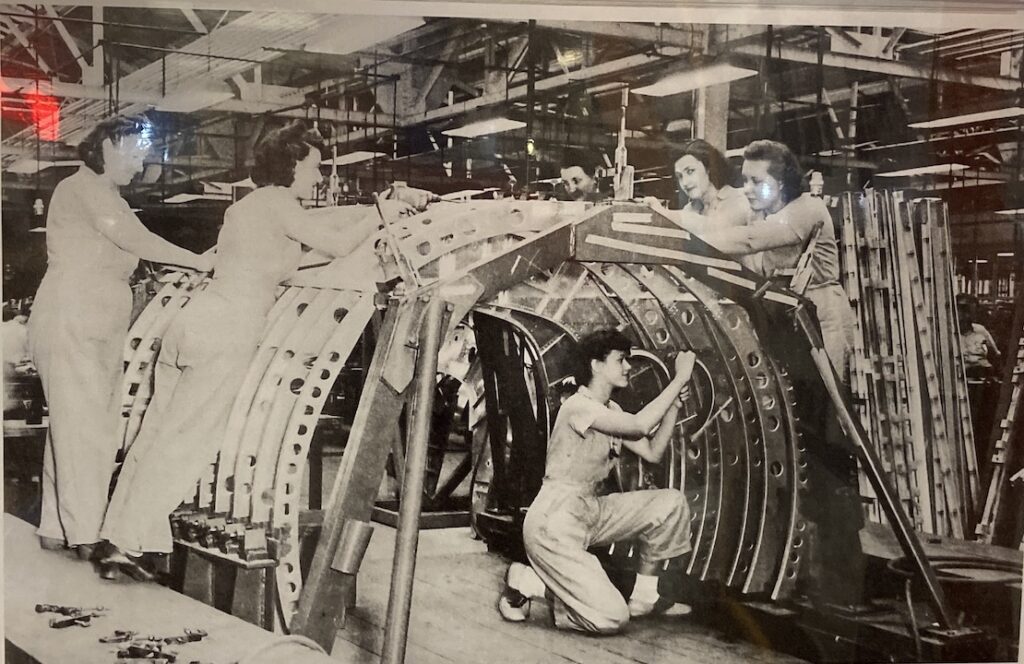

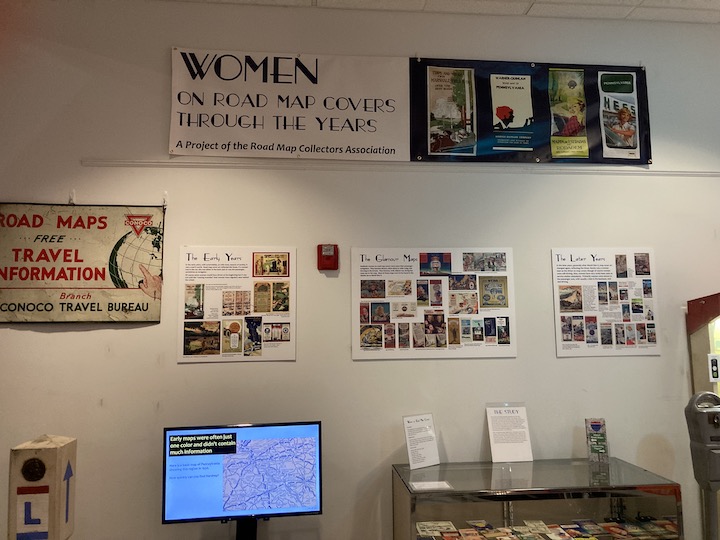

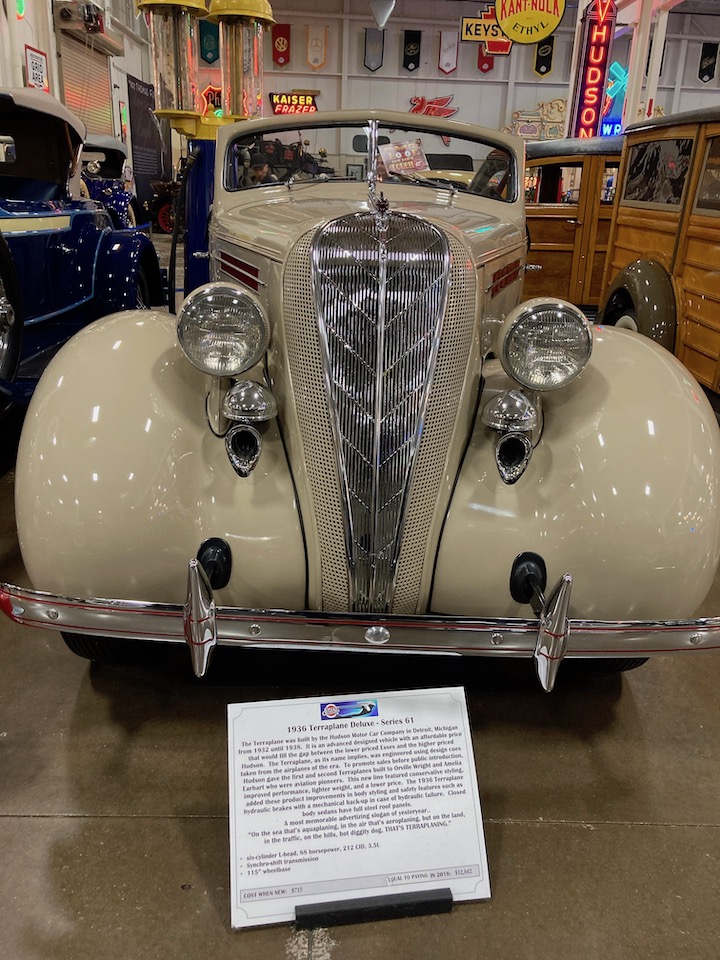

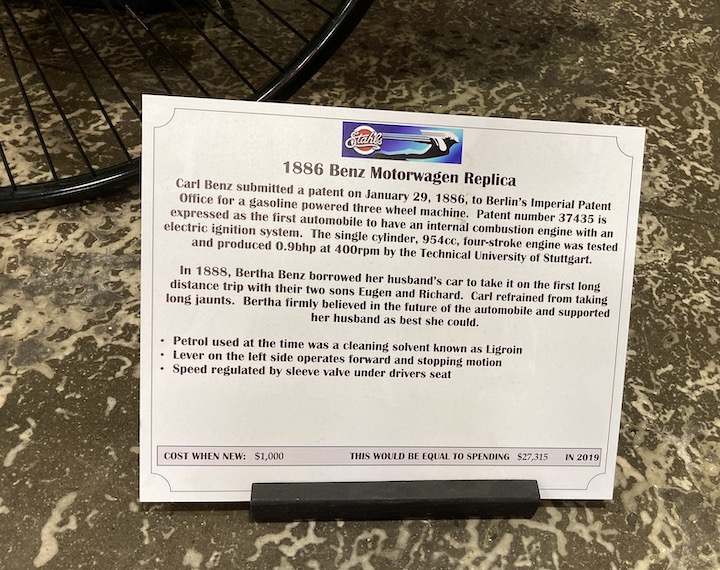

While Mary Stahl’s name appears next to her husband’s on a number of automotive displays as an owner, women’s representation in the museum is minimal and somewhat predictable. Women’s preference for electric cars; Amelia Earhart’s promotion of the 1936 Terraplane; Bertha Benz’s famous road trip; and the custom built automobile of the wealthy Madame Lucienne Benitez-Rexach of France are the only mentions of female automotive involvement. Female imagery is limited to a ‘Rosie the Riveter‘ poster on the gas station wall [next to the rest room] and a couple of female mannequins in the diner display. As Stahl’s is, in fact, the vision of one male individual with very specific and unique automotive and mechanical interests, it is not surprising that representation of women as automotive drivers, users, and influencers are absent in other than the most unsurprising and unimaginative ways.

Auto enthusiasts looking for a fun and unique afternoon will surely enjoy time spent at Stahl’s. As the museum mission is ‘to educate, motivate, and inspire young people with a passion and appreciation for vintage vehicles,’ the staff at Stahl’s endeavors to make the experience memorable and fun for all family members. But if you decide to make a visit, just make sure to bring a set of earplugs with you.