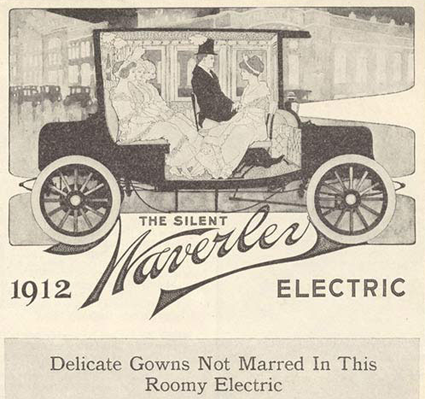

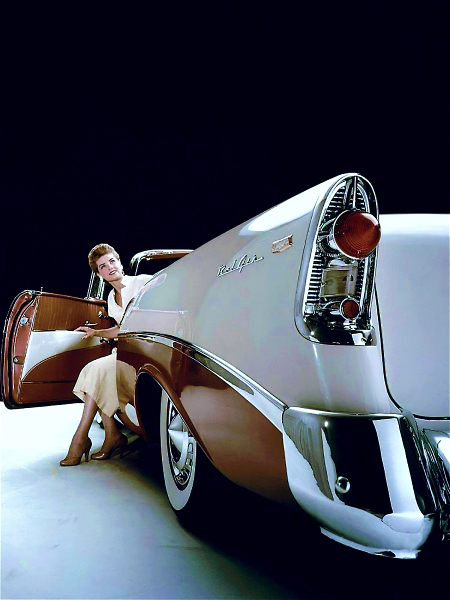

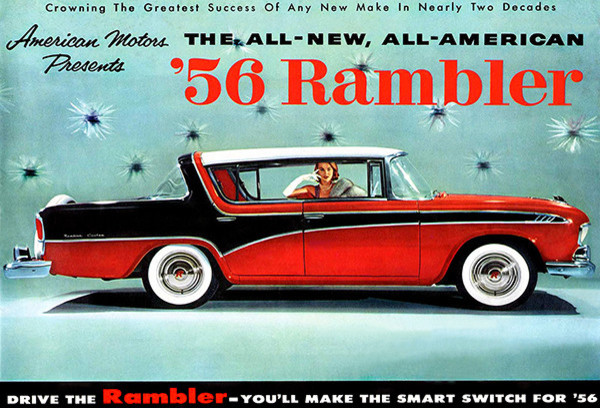

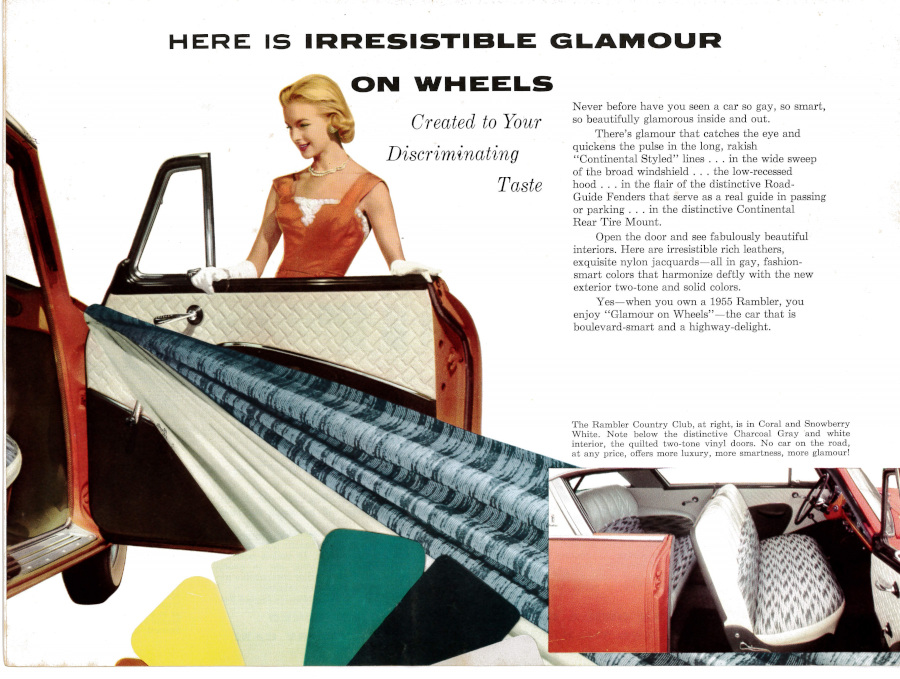

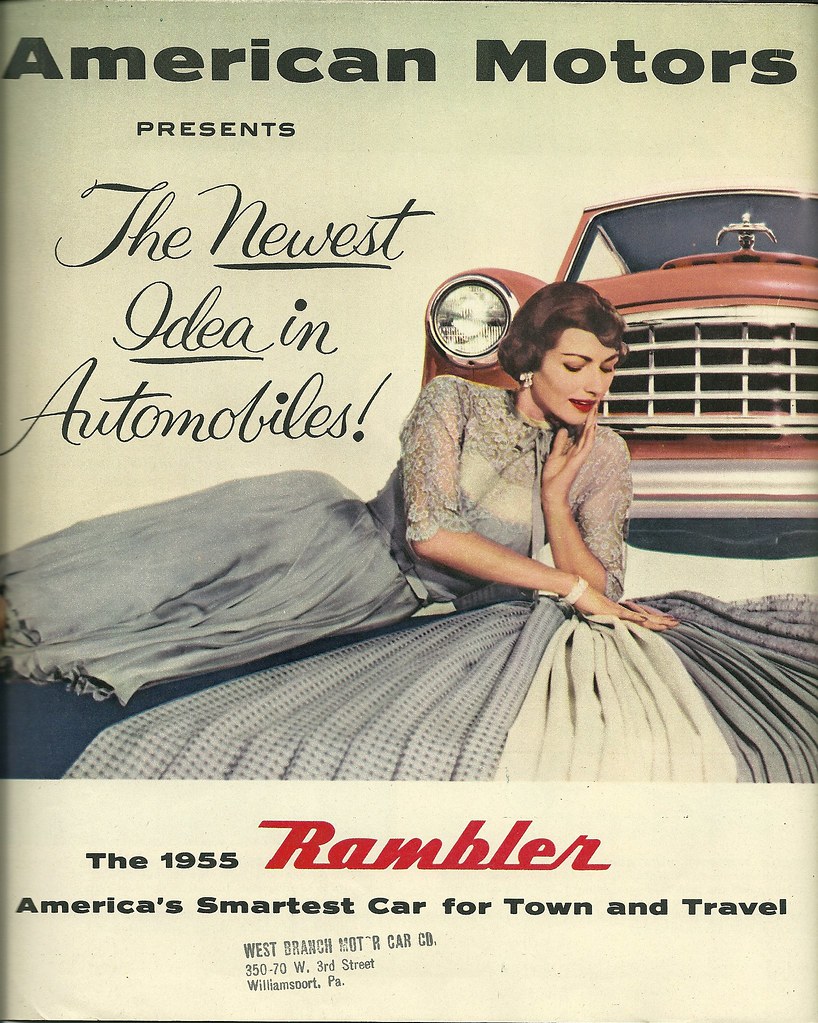

Paul Niedermeyer, writing for Curbside Classics, penned a couple of interesting articles over the past year on the 1950s era Rambler Cross Country. Calling on automotive advertising of the time, Niedermeyer notes how the Rambler was often marketed specifically to the female driver. The Rambler, as ‘the first lifestyle wagon ever,’ was heralded not only for its suitability for growing families, but also for its bold style and unusual, somewhat radical appearance. Advertising was directed not only to suburban moms, but also to fashion-conscious women who desired both practicality and pizazz in the cars they drove. A key part of making the Rambler appealing to women was drawing attention to its interior fabrics and trim, designed by the renowned Helene Rother. As Niedermeyer remarks, ‘a woman’s touch can’t be easily faked.’ Advertising for the Rambler often featured famous women – including American theatre star Margaret Sullavan and the wife of actor Jimmy Stewart – to associate the vehicle with glamour, luxury, class, and discriminating taste. Unlike other automotive advertising of the time, Rambler had a fair amount of success by targeting more affluent and better educated buyers, especially women.

More than a year after the original article appeared, Niedermeyer responded to a previously posted comment that had apparently been gnawing at him for some time. The reader, focusing specifically on the notion that women were important Rambler purchasers, posted, ‘In defense of men, though, many of those 50s women buyers were spending lavishly their husband’s and father’s money.’ Niedermeyer, taking great offense at this comment, countered with multiple examples of how the scenario painted by the defensive reader was unlikely. Calling upon his own experience, he recalled how his father traded in his mother’s car without her knowledge or blessing. As he writes, ‘she was furious, but what was she going to do?’ Niedermeyer also notes that during the 1950s, a growing number of women had careers. In fact, he argues, the targeting of female consumers by Rambler was instrumental in allowing the automaker to survive the early to mid 1950s, when other domestic compacts were failing. Surprisingly [at least to me] Curbside Classic readers – primarily men – joined Niedermeyer in expressing offense to the stereotypical response. Many offered examples of how the women in their respective lives – i.e. strongly opinionated moms, older maiden aunts, and [assumed] lesbian teachers – made their own car buying decisions. Rather than reinforce the generalized stereotype of hapless and uninformed women drivers, the commenters offered a variety of car-purchasing scenarios influenced by family dynamics, finances, marital status, sexual orientation, and the progressiveness of women and men alike.

The Curbside Classic articles caught my attention not only because of the focus on female consumers, but because the author’s comments, as well as those of his readers, brought to mind those of a group of elderly women I interviewed for a project a few years ago. In 2016 I spoke to 21 women in their 80s and 90s – of the same generation of those targeted in 1950s automotive advertising – about their early automotive experiences. Included in the conversations were reminisces regarding individual car histories. Although automakers such as Rambler attempted to lure female customers, the majority of the women I spoke to, when entering marriage, did not have a vehicle of their own, but shared one with husbands. When children appeared on the scene, women fought hard for cars of their own to make their lives easier. However, the majority of these vehicles were not shiny new Ramblers; rather, they were most often described as ‘jalopies’’, ‘clunkers’, or ‘old and cheap’. While there were a few women whose husbands ‘surprised’ them with fancy cars for birthdays or special occasions, most were grateful for anything that offered them a degree of independence.

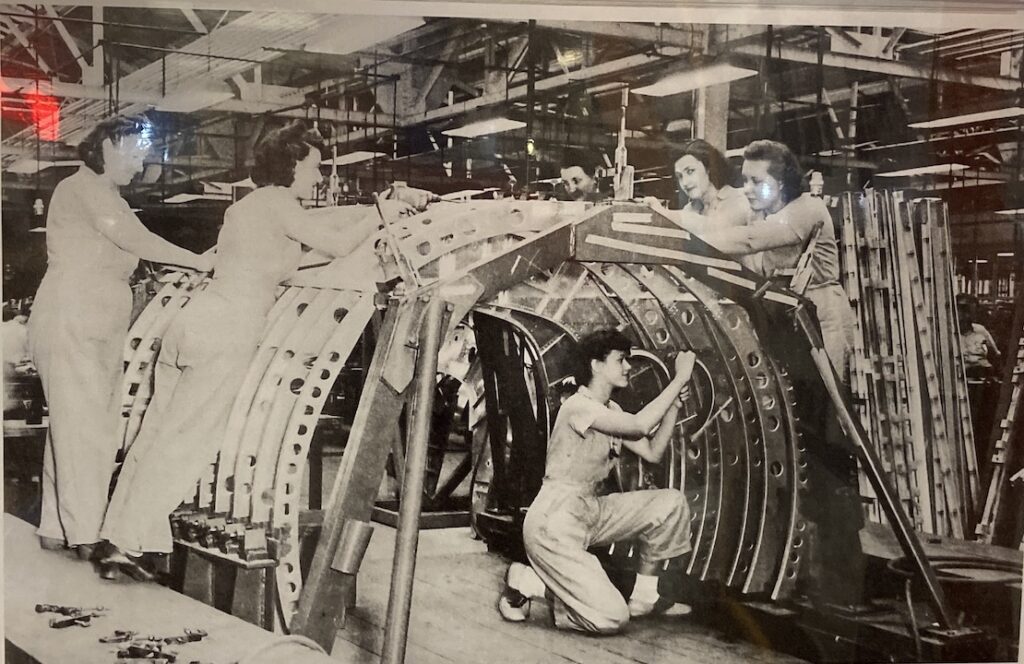

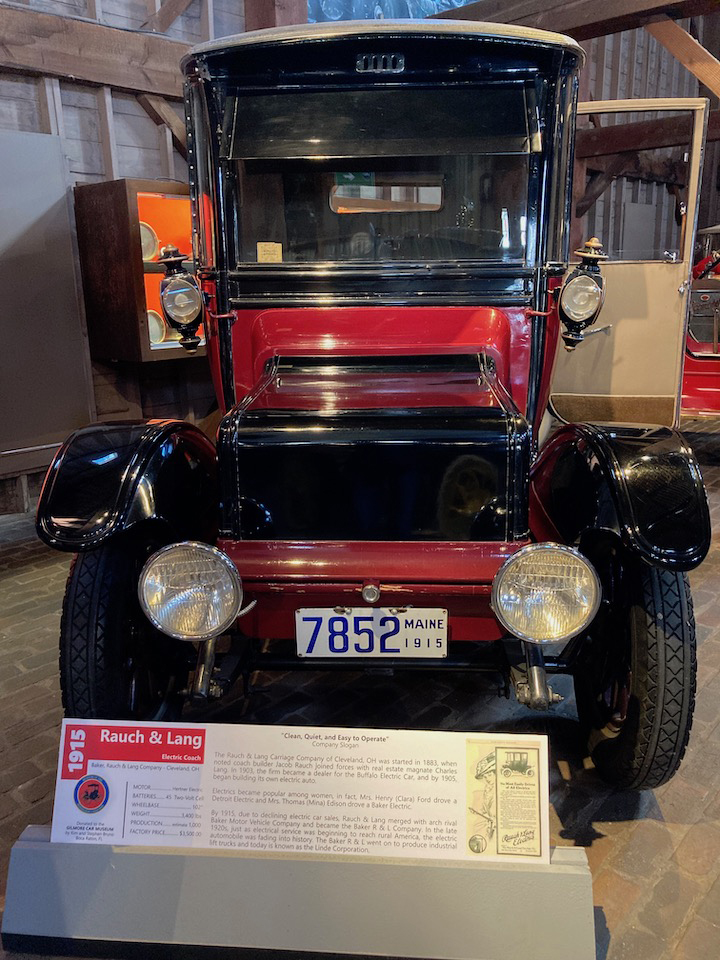

Since many of the women interviewed were located in the greater Detroit area, it was not uncommon for them to work in auto-related industries, or to have friends or relatives who did. This allowed them to purchase a car a family member had previously driven, secure the inside track on a good used vehicle, or take advantage of an automotive employee discount. Others took over the old family car when a new automobile was purchased. Yet no matter how the car was acquired, the women had a definite say in automobile selection, and would accompany husbands to the dealership to make their desires known. If spouses purchased cars without their wives’ input, they often found themselves heading back to the sales office. Not surprisingly, single women – whether unmarried, widowed, or divorced – had the freedom to purchase the car they wanted without male influence or intervention. What became clear from these conversations is that what women wished for in a car – i.e. functionality, economy, and reliability – often differed from the qualities desired by men. Consequently, making their own automotive needs and requirements known was a very important element of the car purchase process. The responses from the women in this project – as well as the Curbside Classic comments – suggests that women were exceptionally influential in car purchases, particularly if it was a car they would be driving. In the present day, it is estimated that women buy 65 percent of all new cars sold in the USA, and influence 85 percent of car buying decisions (Findlay). It is a practice that, as the responses suggest, began as soon as women took the wheel.

Niedermeyer was correct to question the stereotypical comment of one of his readers; i.e. that women’s car purchases were made possible by lavishly spending their husband’s or father’s money. While certainly there were some women who were ‘surprised’ by car purchases made by husbands, the majority of women made their own automotive decisions. As the Curbside Classic articles and my own research suggest, if a woman drove a Rambler, it was most likely because she had the means and the desire to do so.

Findlay, Steve. ‘Women in Majority as Car Buyers, But Not as Dealership Employees.’ Wardsauto.com 20 Sept 2016.

Lezotte, Chris. ‘Born to Drive: Elderly Women’s Recollections of Early Automotive Experiences.’ The Journal of Transport History 40(3) (2019): 395-417.

Niedermeyer, Paul. ‘How Rambler Won the Compact and Price Wars of the 1950s and Saved American Motors.’ Curbsideclassic.com 25 Jan 2021.

Niedermeyer, Paul. ‘She Drives a Rambler’, and No, She ‘Wasn’t Lavishly Spending Her Husband’s Money.’ Curbsideclassic.com 3 October 2022.