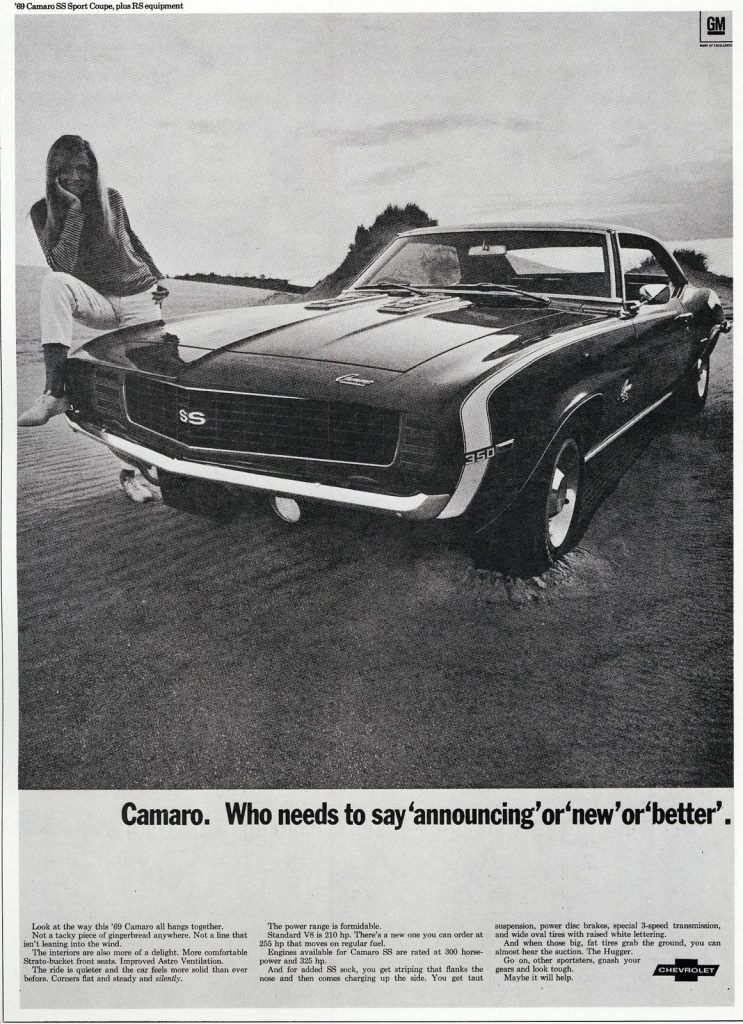

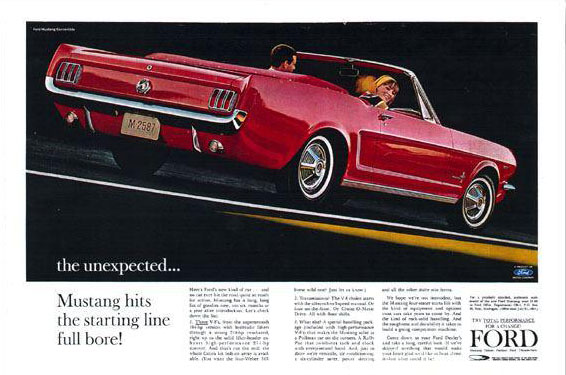

In honor of International Women’s Day, the Ford Motor Company has introduced a rather unconventional marketing campaign which is creating a bit of a buzz. The 30-second commercial, narrated by Brian Cranston of Breaking Bad fame, introduces the Ford Explorer Men’s Only Edition as a completely reimagined vehicle.

Although the advertisement appears to be fairly typical, with running footage of a shiny black vehicle driving down winding roads, it soon takes an unexpected turn. For the special men’s edition is lacking a few important parts, notably windshield wipers, turn signals, a rearview mirror, brake lights, heaters, and GPS, innovations that were, in fact, developed by women. As a nod to women working in automotive industry Ford takes this opportunity to bring attention to the invisible female inventors, engineers, and designers over the past century who have made important contributions to the automobile. As the company website notes, ‘to support the campaign throughout the month, Ford will highlight the achievements and contributions of female innovators of the past and present on Ford.com and across the company’s social media accounts.’

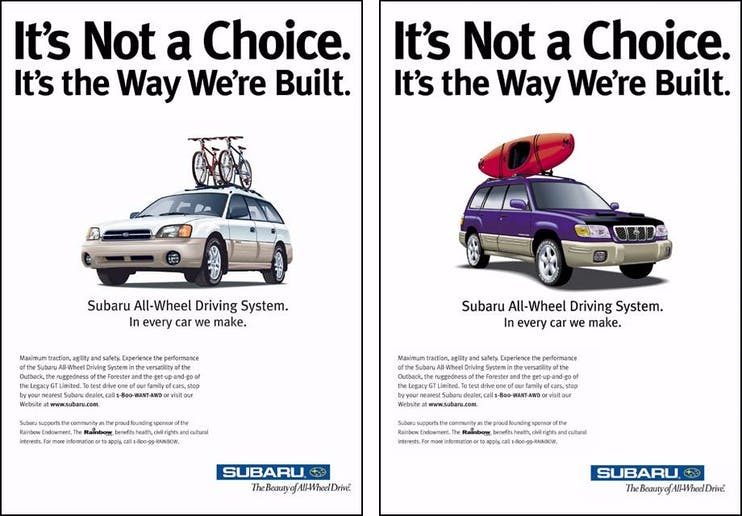

The Ford campaign has made headlines in both the general and automotive press. The reviews have been overwhelmingly positive. Auto journalists refer to the campaign as humorous, tongue-in-cheek, and clever. Many of the articles bring attention to the women responsible for these contributions, including Hedy Lamarr, Florence Lawrence, Dorothy Levitt, Dorothee Pullinger, and Dr. Gladys West. Women in particular are charmed by the commercial, referring to it as ‘10/10 advertisement,’ ‘perfection,’ and ‘makes me even more proud to be a Ford owner.’ As a former advertising person myself, I applaud the Ford ad agency that created a commercial that is not only creative, memorable, and fun, but one that celebrates women without disparaging men.

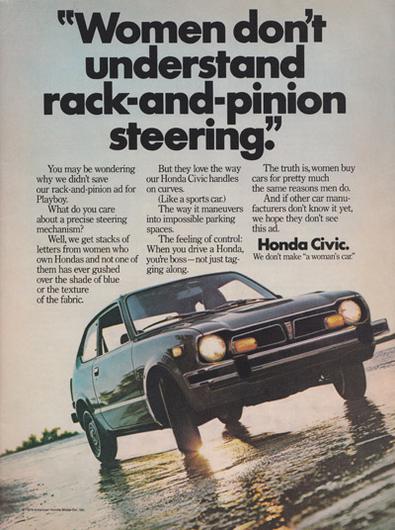

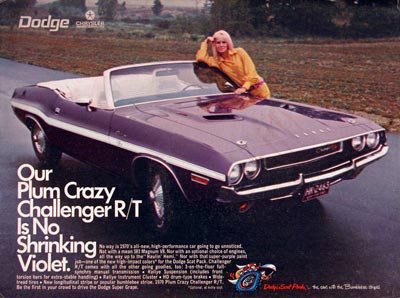

However, not all who viewed this advertisement are pleased. The comment sections on many of the news sites are filled with complaints from those offended, with remarks that suggest the advertisement somehow threatens one’s masculinity. The posts include the unoriginal and expected ‘what is Ford doing for International Men’s Day?’, as well as many that engage in tired gender stereotypes, such as ‘the woman’s only version would only be a small pile of useless parts,’ and ‘since a man invented the internal combustion engine, I’m guessing the women’s addition [sic] would be a static display.’ Some argue that Ford got its facts wrong, with the claim, ‘all of the things mentioned were actually invented by men years before.’ Other individuals go further, admonishing the auto manufacturer for its wokeness and ‘confused’ sexual identity.

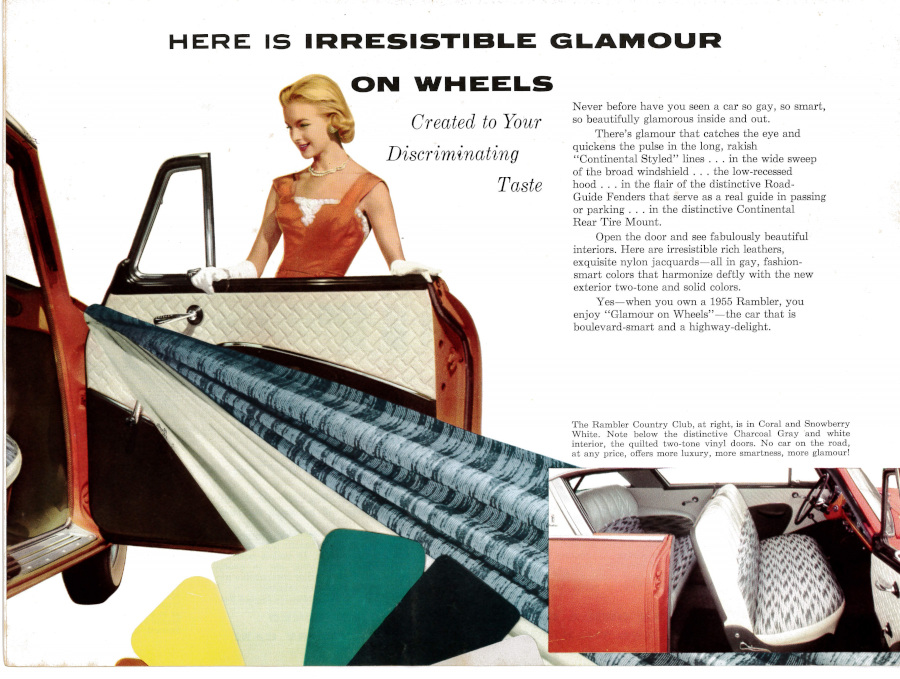

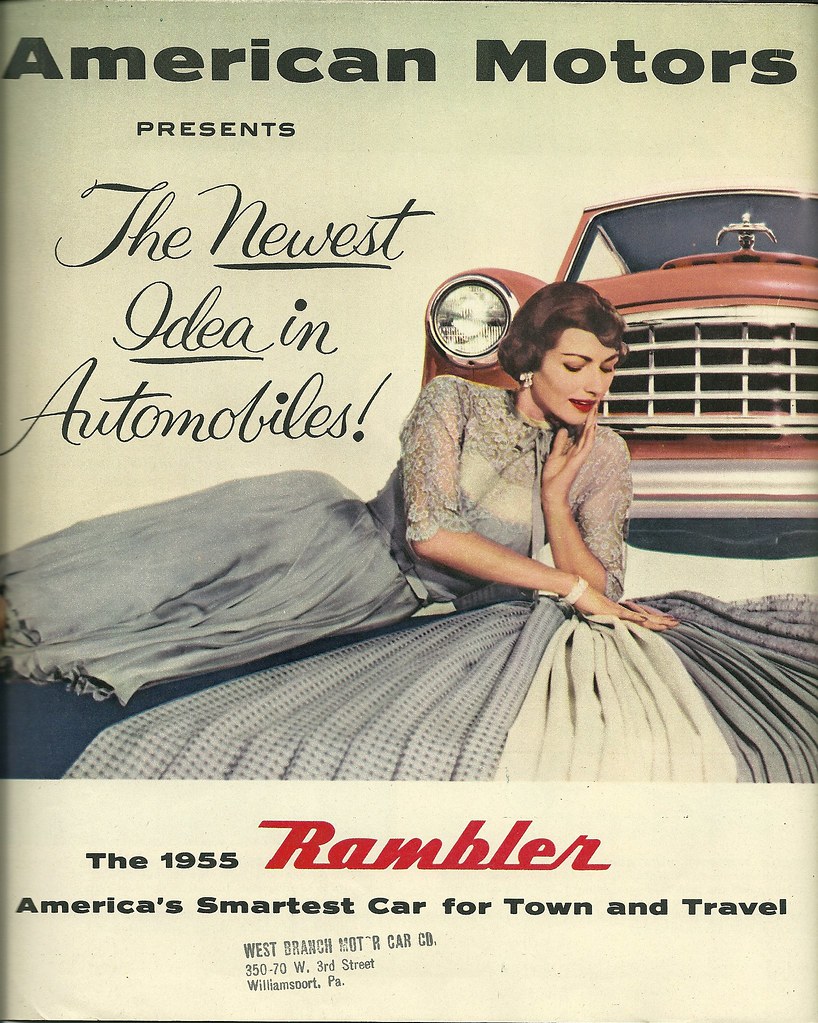

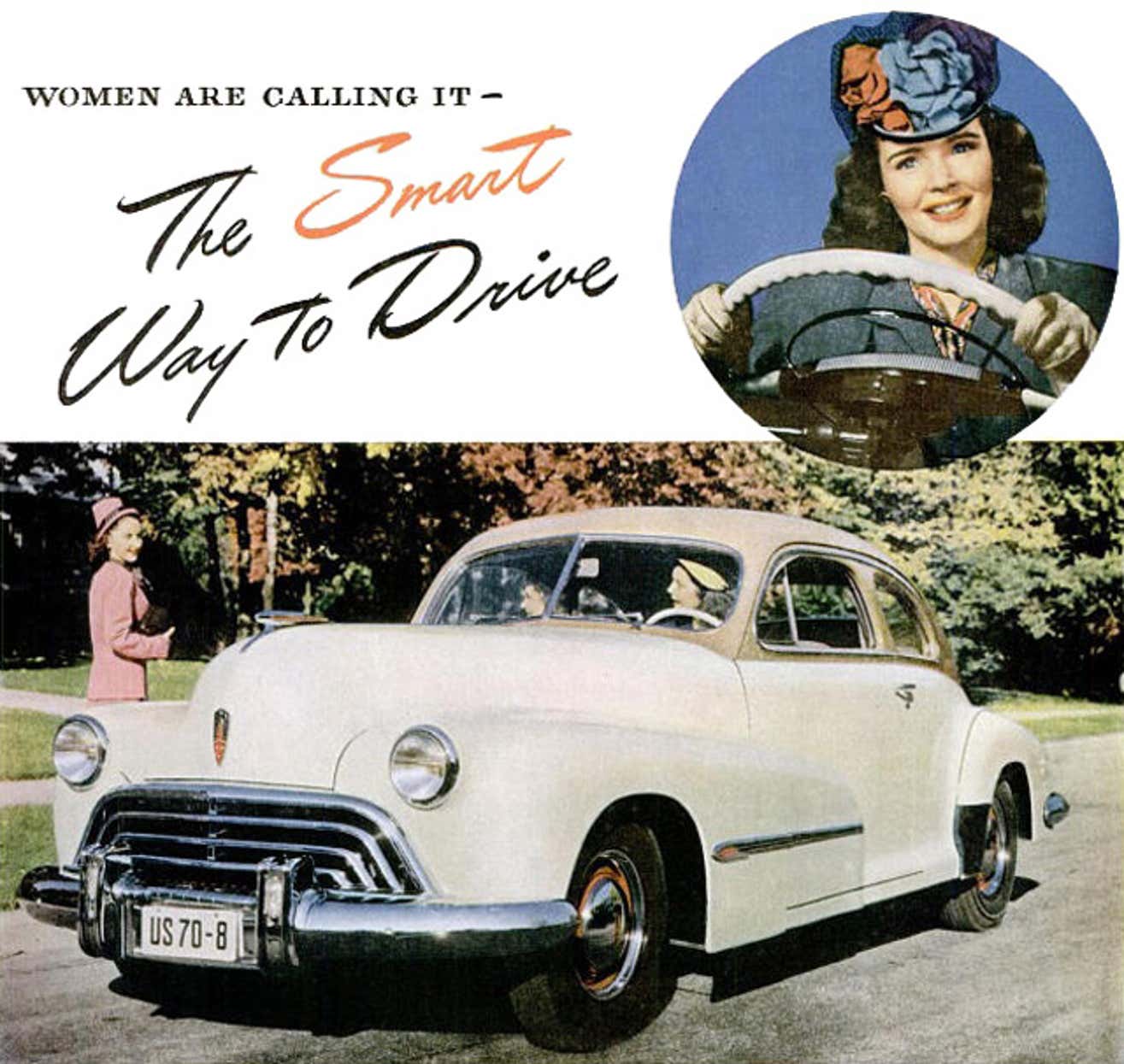

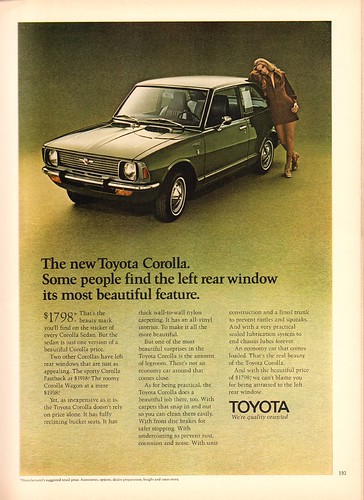

Certainly the comments reflect convoluted logic and a lack of critical thinking, investing in the notion that praising women’s achievements somehow discredits men. Yet what is most troubling in these remarks is the culture they represent. The association between masculinity and the automobile has a long and entrenched history. In the early auto age, in order to perpetuate this ‘natural’ relationship between man and his machine, it became necessity to frame women as poor drivers, mentally incompetent, and technologically ignorant. While the ‘woman driver’ stereotype was developed nearly a century ago to degrade women’s driving ability and automotive competence, the barrage of negative comments incited by a 30 second car commercial suggest such beliefs remain common among a significant [male] population nearly 100 years later. This is worrisome for an individual interested in pursuing an automotive related career. It suggests that the automotive culture remains unwelcoming to women no matter the credentials, work ethic, or job performance. It intimates that despite the efforts within the automotive industry to address the underrepresentation of women, there is still a significant group within it that considers women as less. The sexist commentary not only brings renewed attention to the incredible obstacles faced by women in the automotive industry a century ago, but reveals that in the twenty-first century, many of those barriers stubbornly remain.

Ford is to be commended for celebrating women’s automotive achievements in this clever and thought-provoking ad. It provides the opportunity for all of us who drive – men and women alike – to appreciate and respect the automotive innovations contributed by women in a historically male-dominated industry.