This past weekend my automotive museum project took me to the Ford Piquette Avenue Plant in downtown Detroit. Constructed in 1904, the Piquette Plant was the second center of automotive production for the Ford Motor Company. From 1904 until the end of 1909, the facility assembled Ford car models B, C, F, K, N, R, S, and T [known as the Ford alphabet cars]. The most famous is the Model T, the car credited with initiating the mass use of automobiles in the United States. The Model T was initially produced [station to station assembly] at the Piquette Plant in 1908; it was subsequently mass produced when the company transferred its operations to the Highland Park Assembly Plant in 1913. After Ford vacated the Piquette building, it had a series of owners before being sold in 2000 to the Model-T Automotive Heritage Complex, Inc, which restored the plant and now operates the historic site as a museum.

Automotive museums, as I’m discovering, most often reflect the interests and inspirations of the founders. While there are many institutions devoted to a particular automotive manufacturer, the focal point of the Paquette one specific model – the Model T and the alphabet cars that preceded it. There are 60 cars of various provenance on two floors; the building also houses a reconstruction of Henry Ford’s office and provides a good deal of background on the daily operation of the factory back in the day. Many of Ford’s early automotive projects which took place at the Paquette are documented and on display.

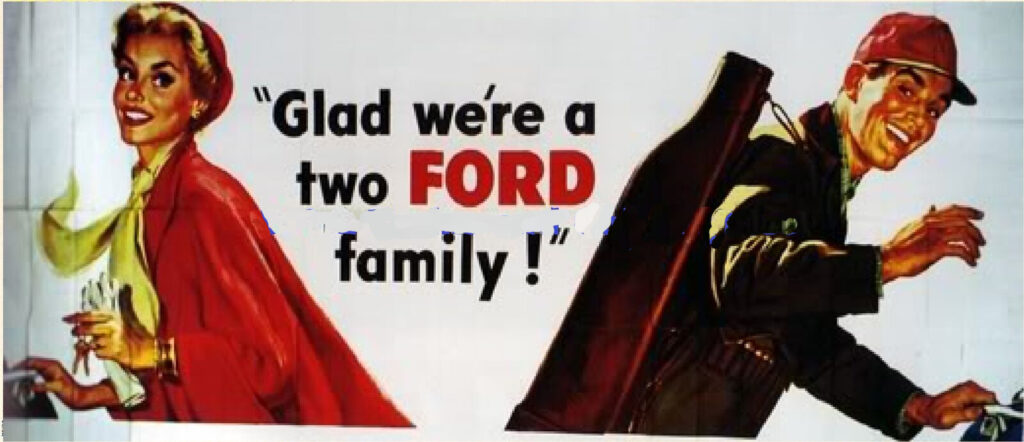

As to be expected in a museum housed in a former automotive factory, which operated during a time when the automotive industry was owned and operated almost exclusively by white men, women’s presence as consumers, drivers, or workers is limited. However, if one looks hard enough at the various exhibits women’s influence surfaces in both stereotypical and unexpected ways.

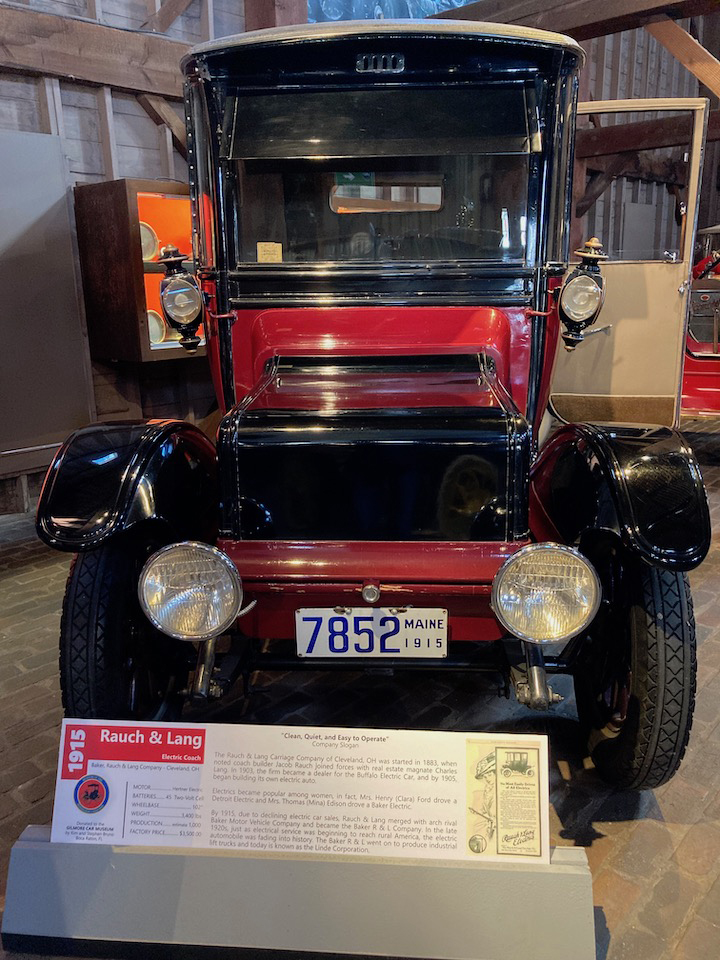

Clara Ford, Henry’s wife, is referenced often in the museum. Perhaps most impressive is her role in the testing of what became known as the Kitchen Sink Engine Model. As Ford lore would have it, on Christmas Eve, 1893, the apparatus was placed over the sink in the Ford family kitchen while Henry worked the ignition and Clara fed gasoline into the intake valve. As noted by auto aficionado Bill McGuire, ‘when the simple, hand-built engine sputtered to life over the sink, Ford’s earliest dream was realized and his remarkable automotive career began.’ Clara is also mentioned in connection to the museum’s non Ford electric vehicle. This story, that Henry purchased the electric vehicle from an automotive competitor for his wife, is one that can be found in nearly every Ford exhibit in any museum. Of course, the question of whether Mrs. Ford actually desired the vehicle, or rather it was purchased to keep her close to home, is never answered.

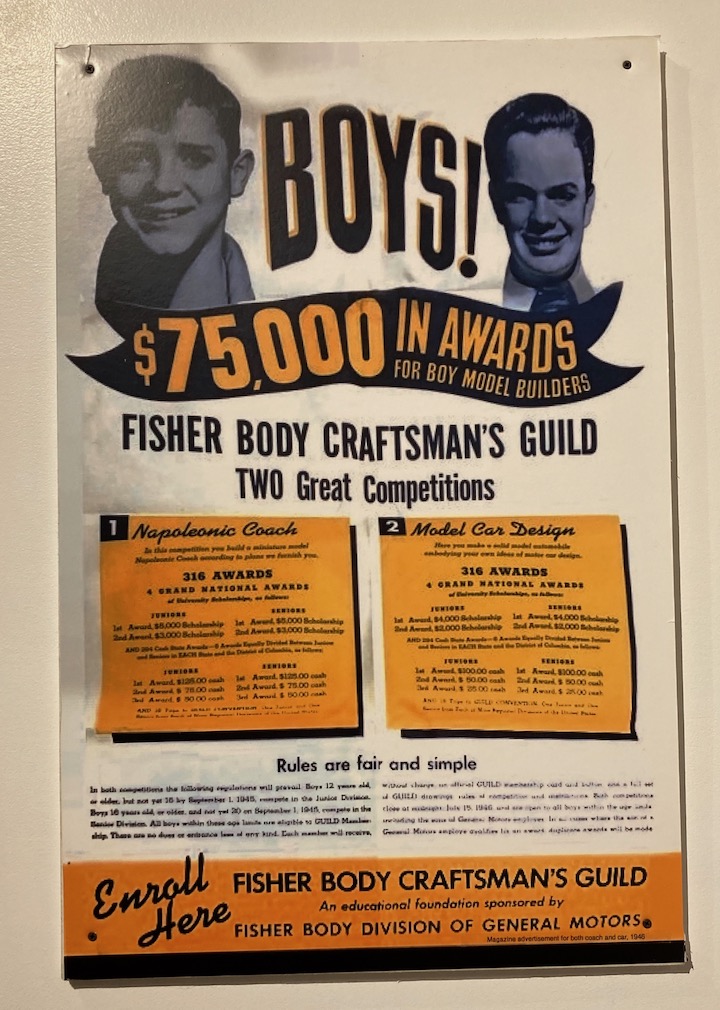

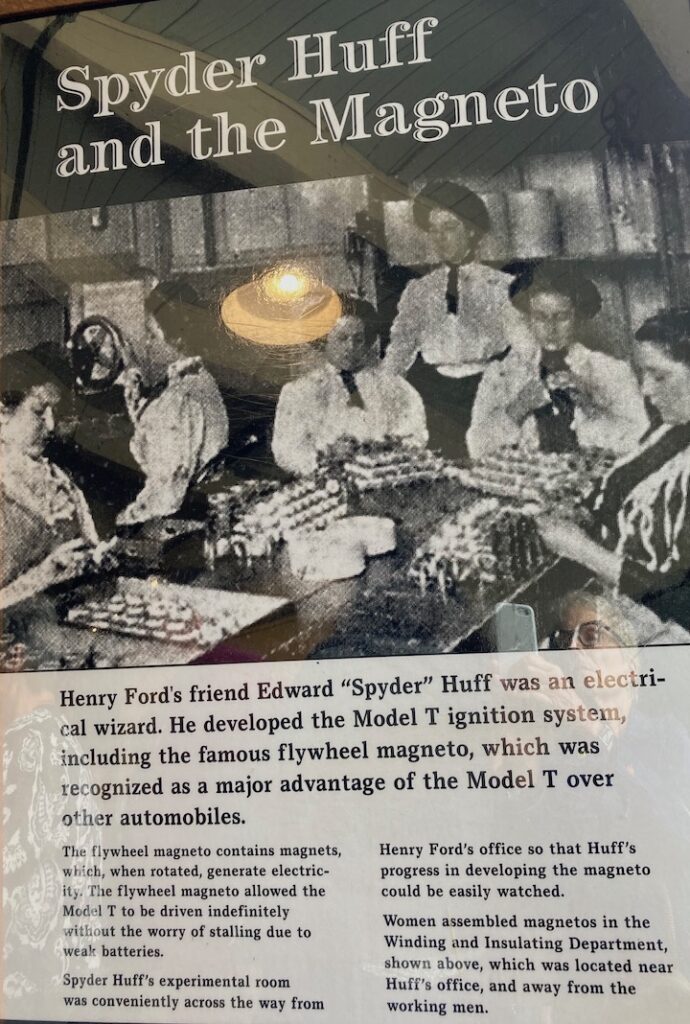

Another interesting exhibit in which women are prominent is that dedicated to automotive inventor Edward ‘Spider’ Huff. Huff helped to perfect the enclosed flywheel magneto – recognized as a major advantage of the Model T over other automobiles of the time. The magnetos were assembled by a team of women in the Winding and Insulating Department, located near Huff’s office and away from the working men. This group of workers were the first women to be employed by Ford. This hidden bit of information also provides a little insight into Ford as a segregated work environment.

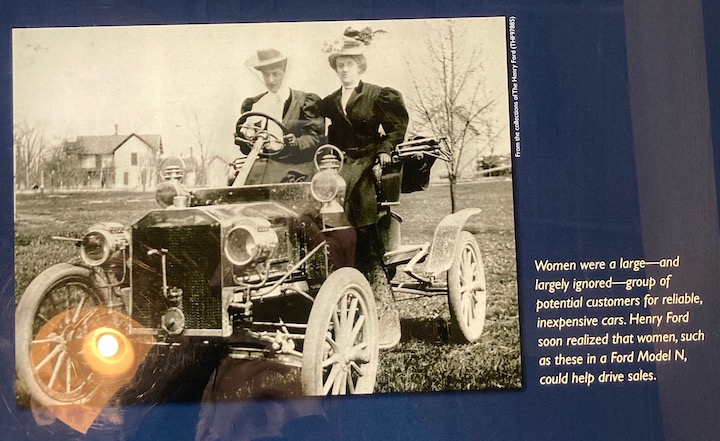

Other references to women include photos of women behind the wheel of Model Ts as well as operating bicycles. Tucked into a corner on the second floor is a photo of women drivers with a caption that notes that, although women were routinely ignored by the auto industry, Ford recognized them as an important market for reliable, inexpensive cars.

One of the more interesting options of some of the early Fords was the ‘mother-in-law’ seat, a fold down, single person rumble seat in the rear. The commonly used term for this feature no doubt reflects some of the ‘back seat driver’ stereotypes of the time.

We arrived at the museum in time to join the last tour of the day. The tour was a bit rushed, as the facility was being set up for a wedding later that evening. While the tour guide was quite knowledgeable, he was also a bit sexist, embellishing or perhaps even fabricating stories about women’s preferences for particular automobiles. According to this gentleman, women were attracted to the 1907 Model R Runabout for its extensive ‘bling’; to the 1911 Brush Runabout for its easy ride and affordability; and the electric car for its high roof [to accommodate women’s hats], its extensive use of glass [so that women could be ‘seen’], and the seats arranged in living room fashion to ease conversation. None of this was documented in the museum; I suspect it was the guide’s attempt at being ‘funny’ to a captive audience.

The Ford Piquette Avenue Plant is an interesting and historically significant building that provides a unique chapter in the history of the Ford Motor Company. It is certainly worth a visit if you find yourself in downtown Detroit.