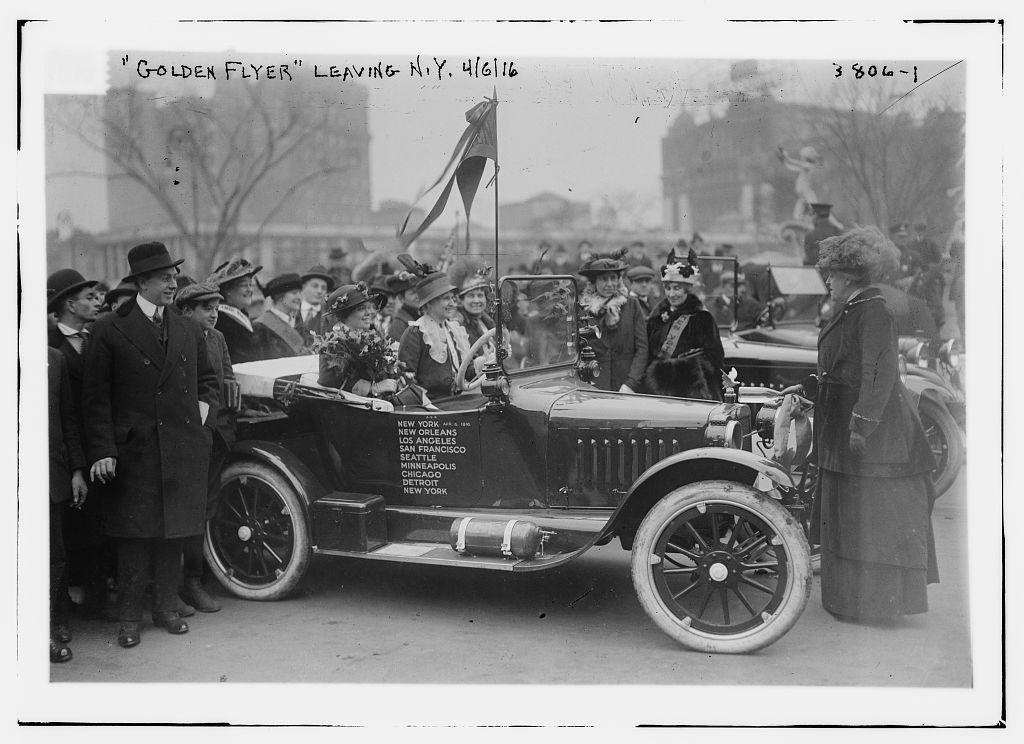

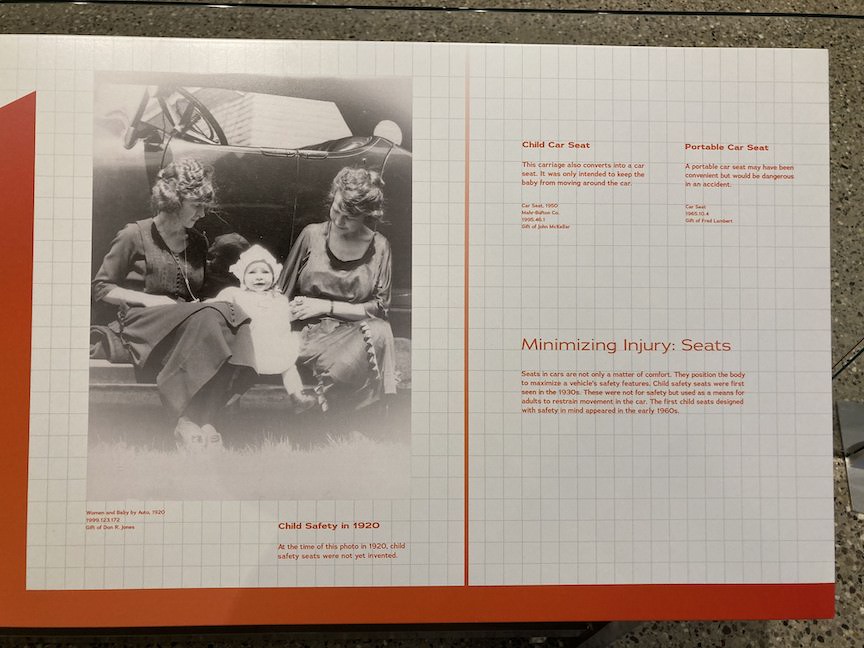

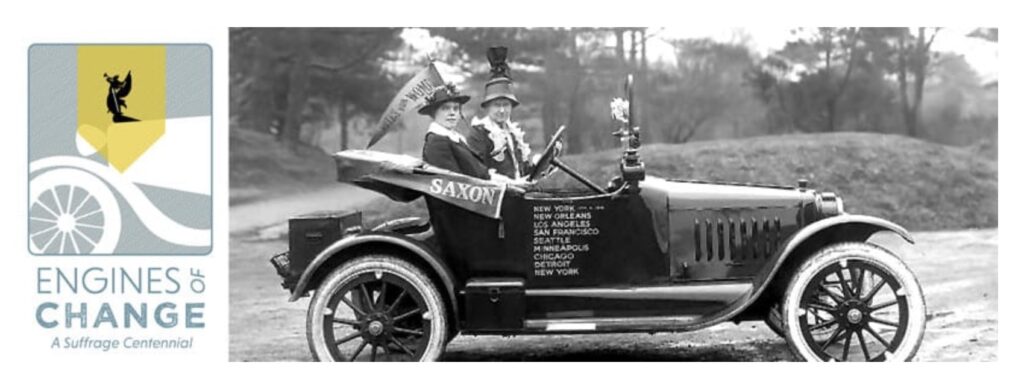

In my quest for evidence of women’s automotive history in museums centered on the automobile, one of the categories I encountered from time to time was the ‘special exhibit.’ These exhibits are often put together to commemorate certain events in women’s history. The 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in 1920, which unfortunately occurred during COVID, was an occasion to assemble various artifacts related to women’s attainment of the vote. The automobile was an important tool in the suffrage campaign. In the spring and summer of 1916, the transcontinental suffrage tour from New York to San Francisco was one of the actions taken to spread the word of the importance of the women’s vote as well as “to persuade male party leaders to include woman suffrage platforms at both the Republican and Democratic national convention” (Lesh 136). The automobile was not only called upon as the primary mode of transport, but also served as a platform on which to speak and the means of a quick getaway should crowds get hostile. It is not surprising, therefore, that the anniversary of women’s enfranchisement was a popular motive for a women’s automotive history exhibit, even though the pandemic caused many of the displays to be postponed a year or two.

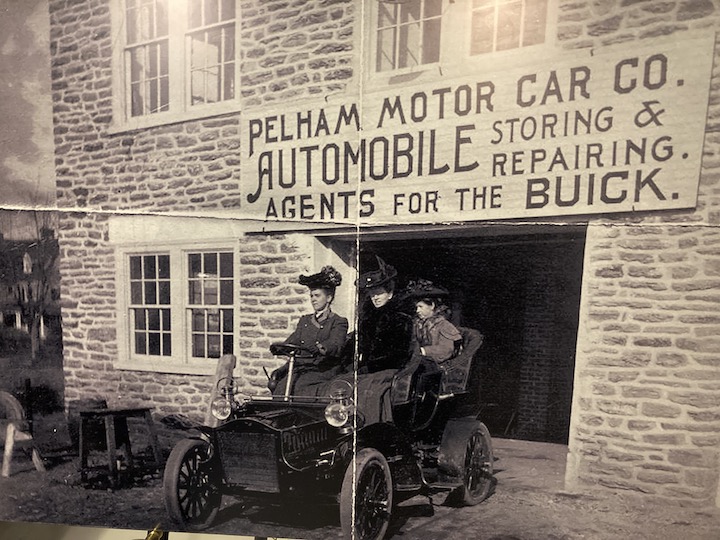

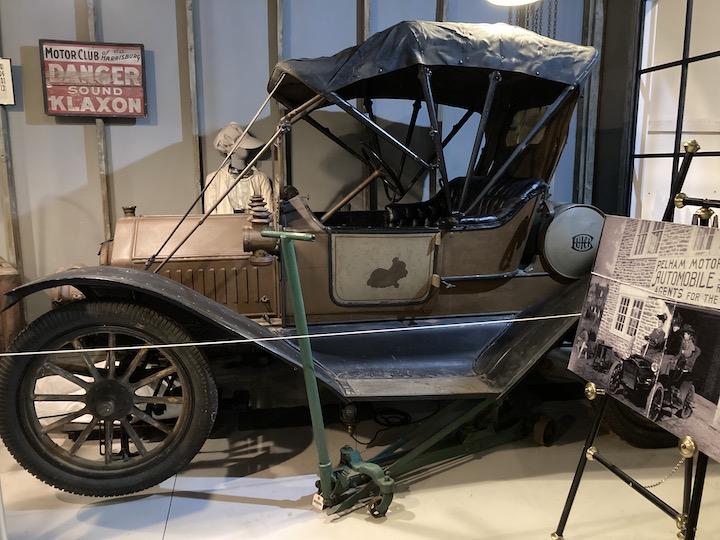

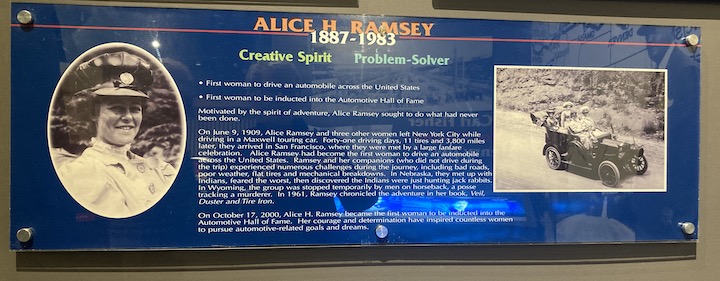

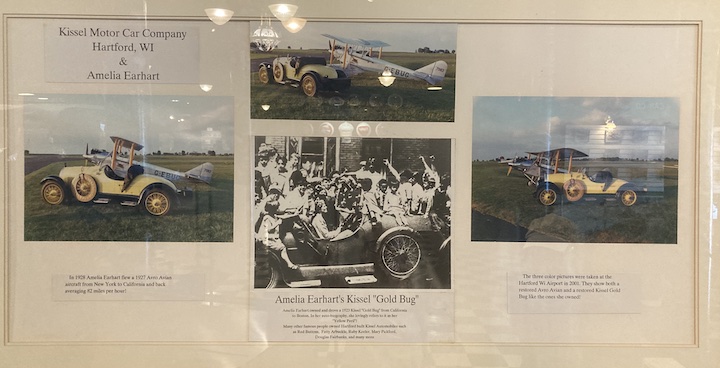

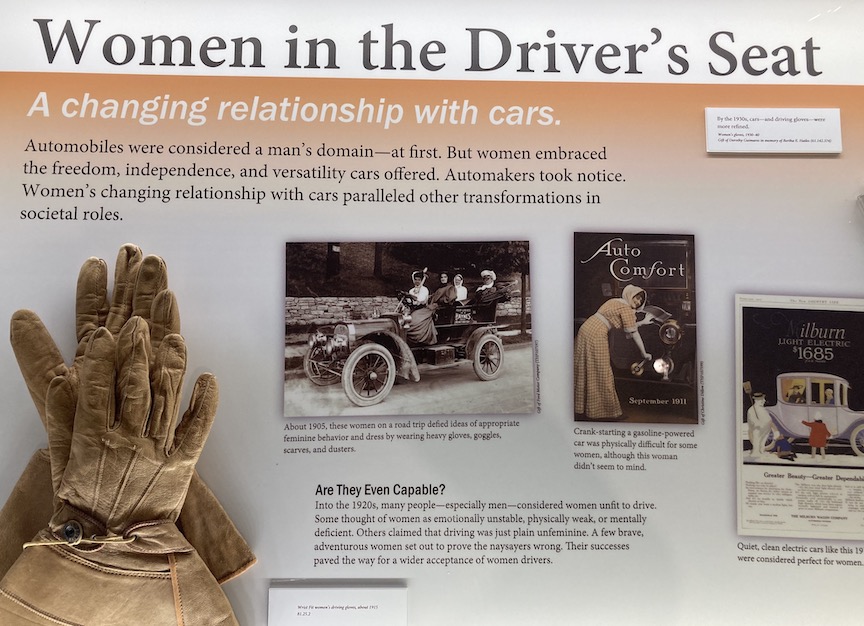

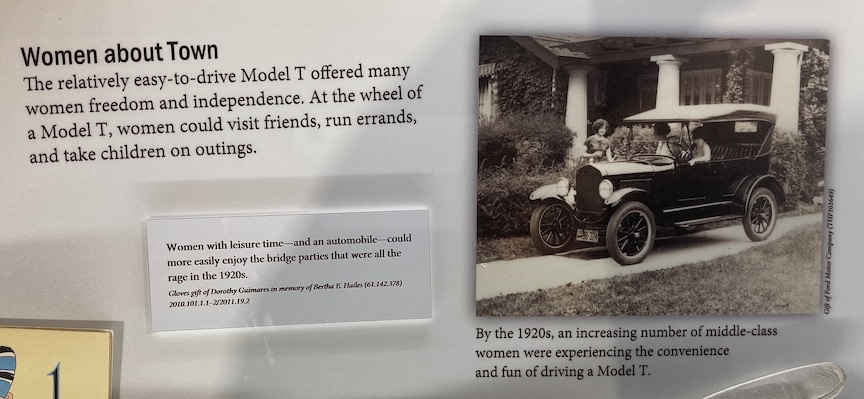

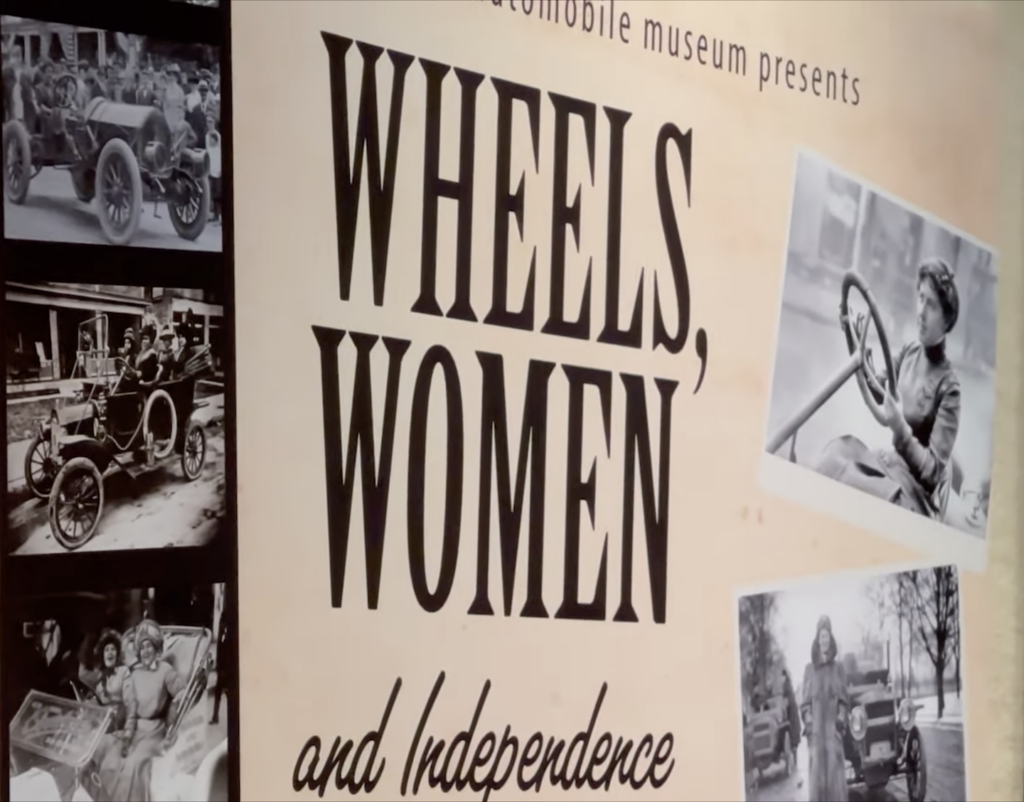

‘Women Who Motor’ was such an exhibit. It made its debut at the historic Edsel and Eleanor Ford house in the Detroit suburbs, then moved to the Gilmore Car Museum in Hickory Corners, Michigan. The display featured a reproduction of the Motorwagen driven by Bertha Benz to advertise her husband’s invention, an 1899 Locomobile steam runabout like the one Joan Newton Cuneo purchased to enter the AAA’s inaugural Glidden Tour, as well as stories and photographs featuring female automotive legends including Alice Ramsey, Helene Rother, Margaret Elizabeth Sauer, Audrey Moore, Betty Skelton, and Danica Patrick. As the Gilmore teams notes, “this exhibition offers a glimpse into the world of women and the automobile. It is designed as a jumping off point for your own exploration into how the automobile has influenced women, and how women have influenced the automobile.”

Women’s History Month is also an occasion to draw attention to women’s automotive achievements. While many museums create special displays to honor women in automotive, they are often are a collection of artifacts the museum already possesses, grouped together for the month of March. As Helen Knibb writes, “The first and often only opportunity curators may have to introduce women’s history to the public comes through temporary exhibitions on special themes. But temporary exhibitions exist for a fixed period and are then dissolved” (356).

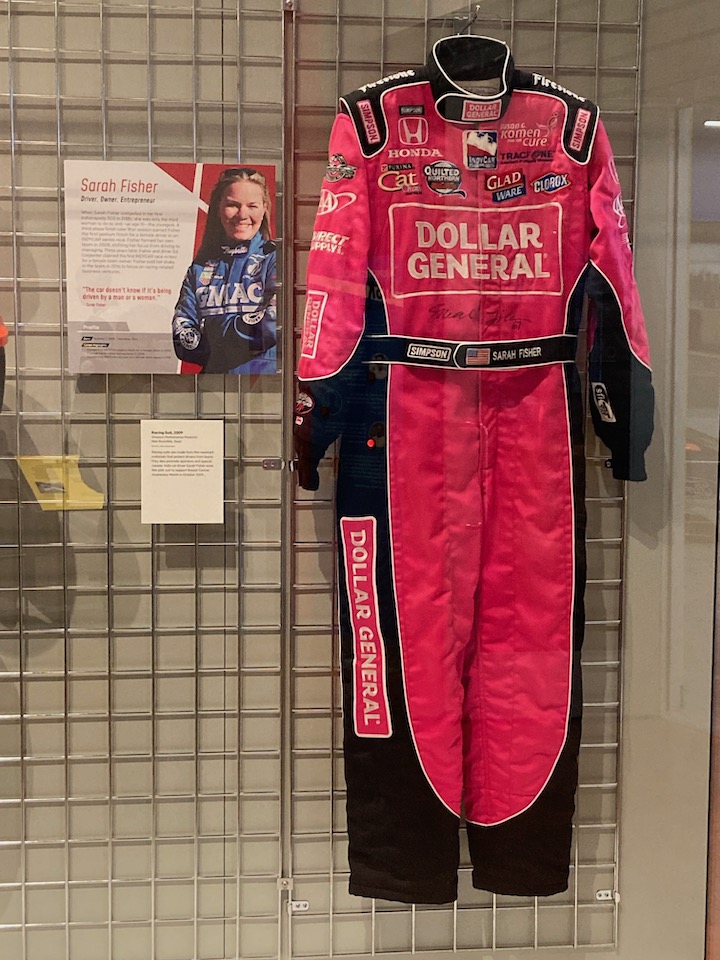

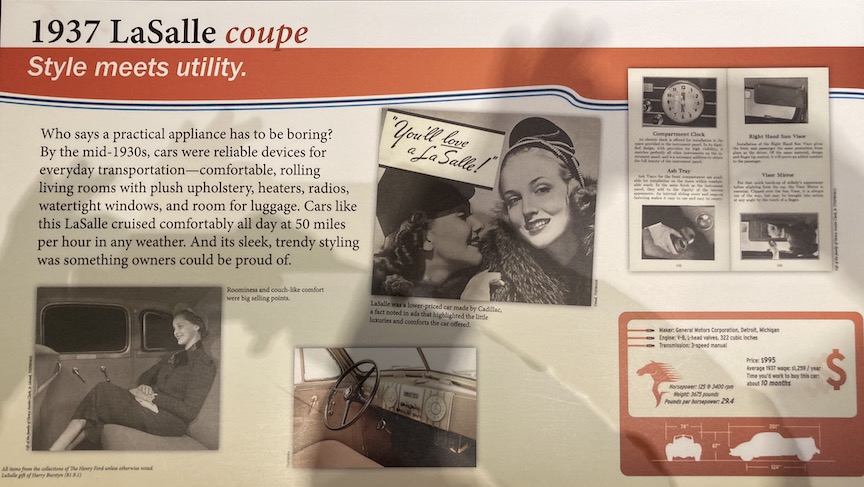

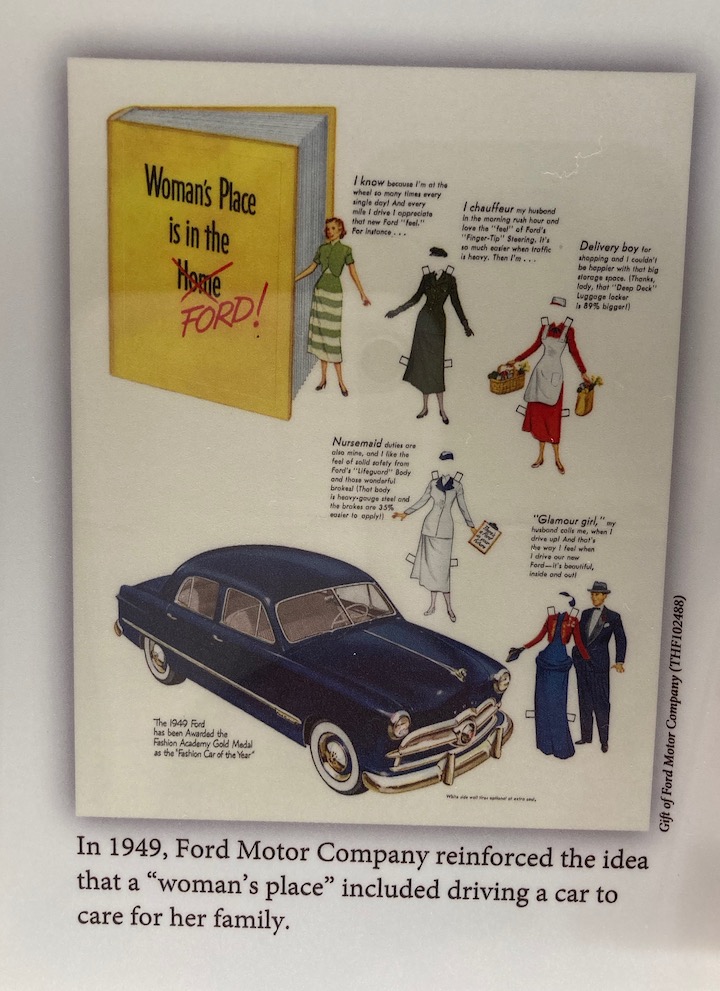

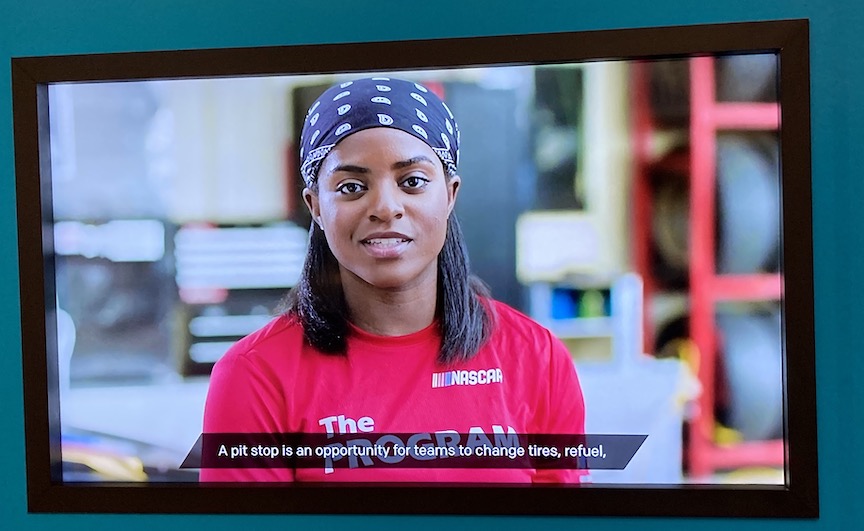

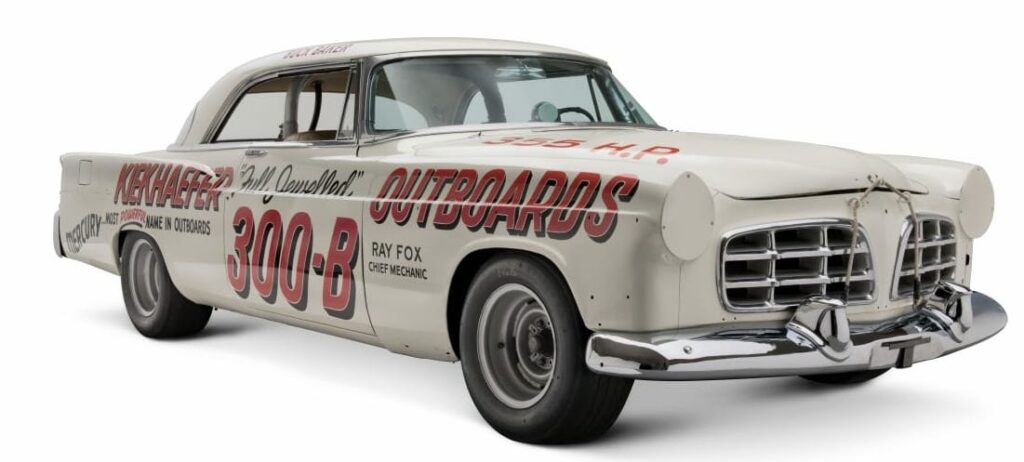

The Henry Ford created a number of these exhibits in March 2024. While the displays included female achievements in a wide variety of endeavors, special attention was given to women’s relationship to the automobile. Within the Henry Ford museum a display was created to celebrate women in racing. Featured artifacts included the Chrysler 300 driven by Vicki Wood at Daytona Beach in 1960, the racing glove worn by Janet Guthrie in the 1977 Indianapolis 500, as well as Sarah Fisher’s racing suit, worn during her third place finish at the Kentucky Speedway in 2000. The Ford Rouge Factory Tour, park of the Henry Ford experience, focused on significant innovations and contributions to the automotive industry made by female inventors and entrepreneurs. Accompanying the main exhibit were interactive displays that offered adults and children the opportunity to engage in Women’s History Month activities

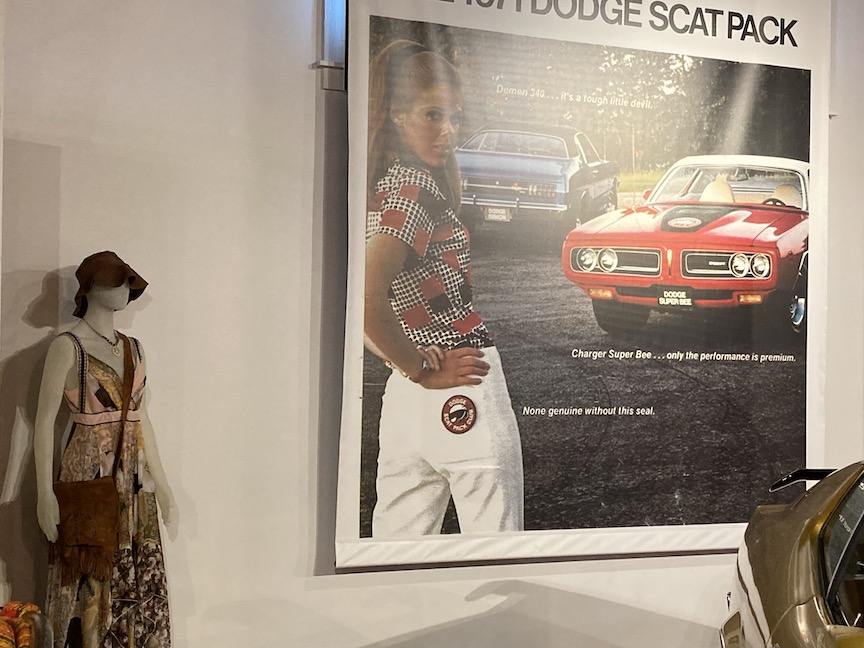

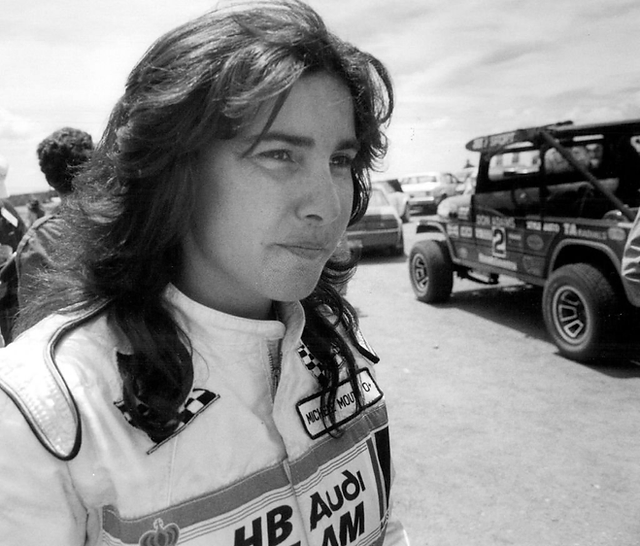

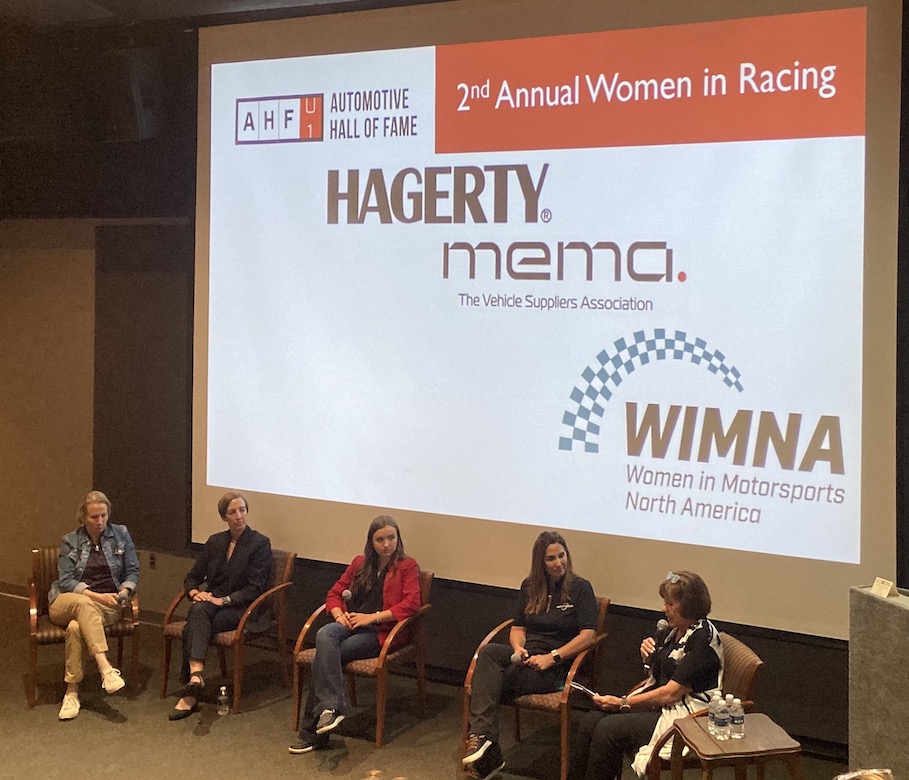

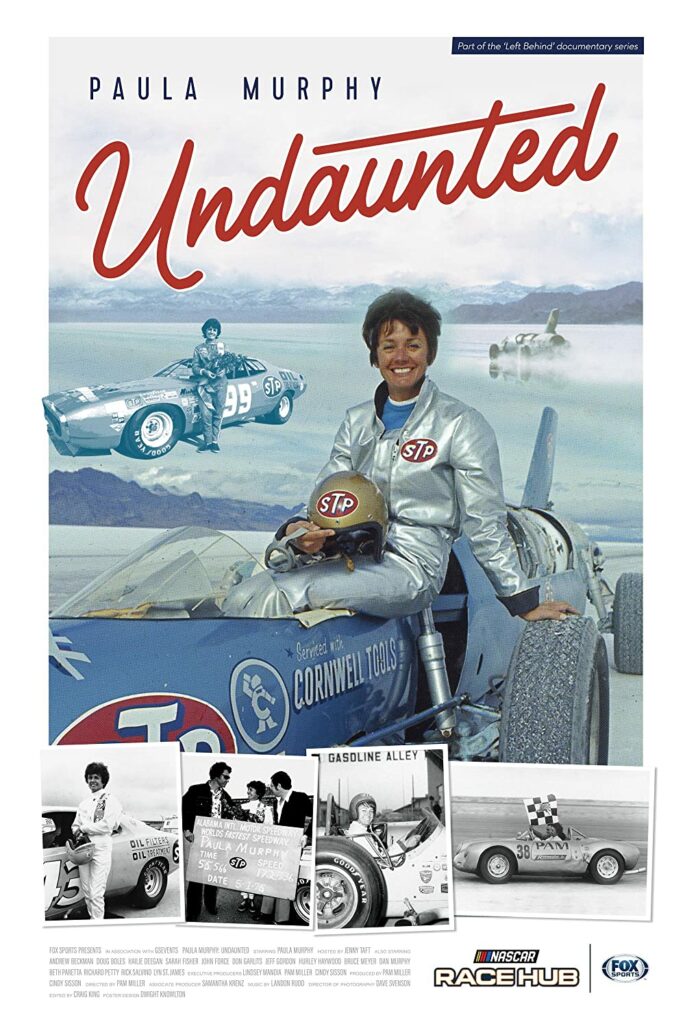

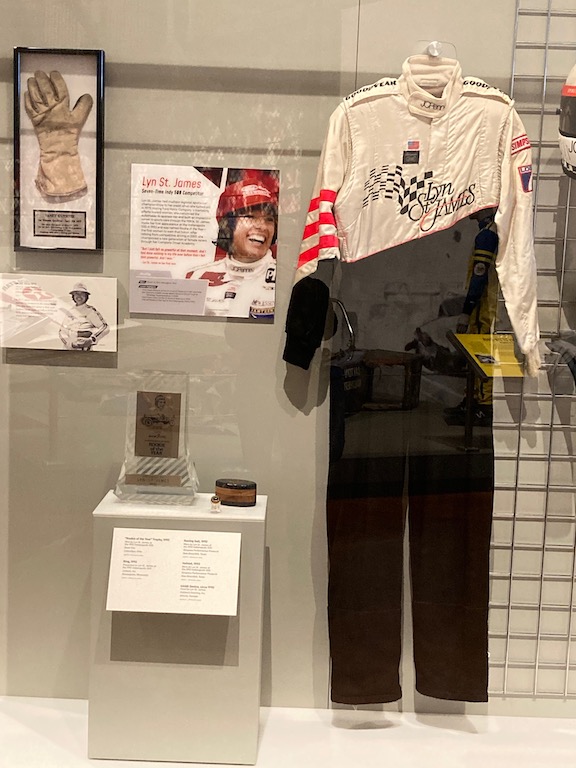

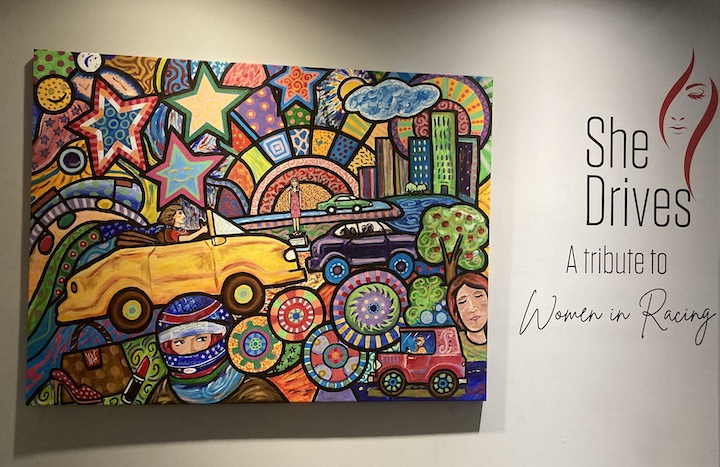

I recently had the opportunity to visit a special exhibit at the Automotive Hall of Fame. ‘She Drives’ celebrates racing’s pioneering women. The exhibit includes stories of 11 inspiring women “shaped through their stories artifacts, and cars that shaped their paths.” Featured race car legends include Bertha Benz, Janet Guthrie, Lyn St James, and Shirley Muldowney. There is also an opportunity to participate in the She Drives Road Tour, which includes a visit to the exhibit at AHF as well as stops at other museums and places of interest in the metropolitan Detroit area.

While racing and suffrage are common women-in-automotive-history exhibit themes, the most unusual and fascinating exhibit I encountered was that of female low riders featured at the California Automobile Museum this past April. This exhibit was not just a collection of artifacts packed away in the museum’s archives, but a carefully constructed original display that imaginatively reflected the region’s lowrider history and culture. I suspect that this is a traveling exhibit that will eventually make its way to other museums in the state.

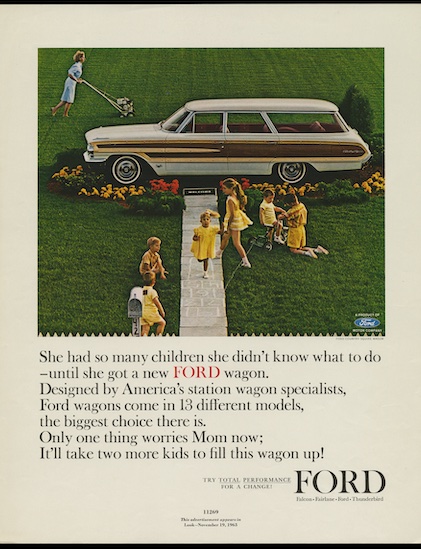

While special exhibits provide an opportunity for automotive museums to draw attention to women’s relationship to the automobile, it is unfortunate that such attention is most often limited to special occasions. Such exhibitions, Knibb argues, require museums “to reassess the balance of exhibition theme and included the ‘underside’ of history, topics which have traditionally been poorly documented or under-represented in exhibition” (357). As Knibb notes, museum collections are often shaped by what the museum has – the ‘survival of objects and the personal tastes of donors’- rather than by any planned efforts to collect and develop artifacts representative of women’s automotive participation (361). Perhaps increased attention to women’s automotive history within the museum would plant the seed for additional informative, educational, and inspirational donations so that women’s contributions would not only be pulled out for ‘special’ occasions, but would be permanently on display as integral to the museum’s automotive collection.

Knibb, Helen. “Present But Not Visible: Searching for Women’s History in Museum Collections.” Gender & History 6, 3 (November 1994): 352-369.

Lesh, Carla R. Wheels of Her Own: American Women and the Automobile, 1893-1929. Jefferson NC: McFarland & Company, 2024.