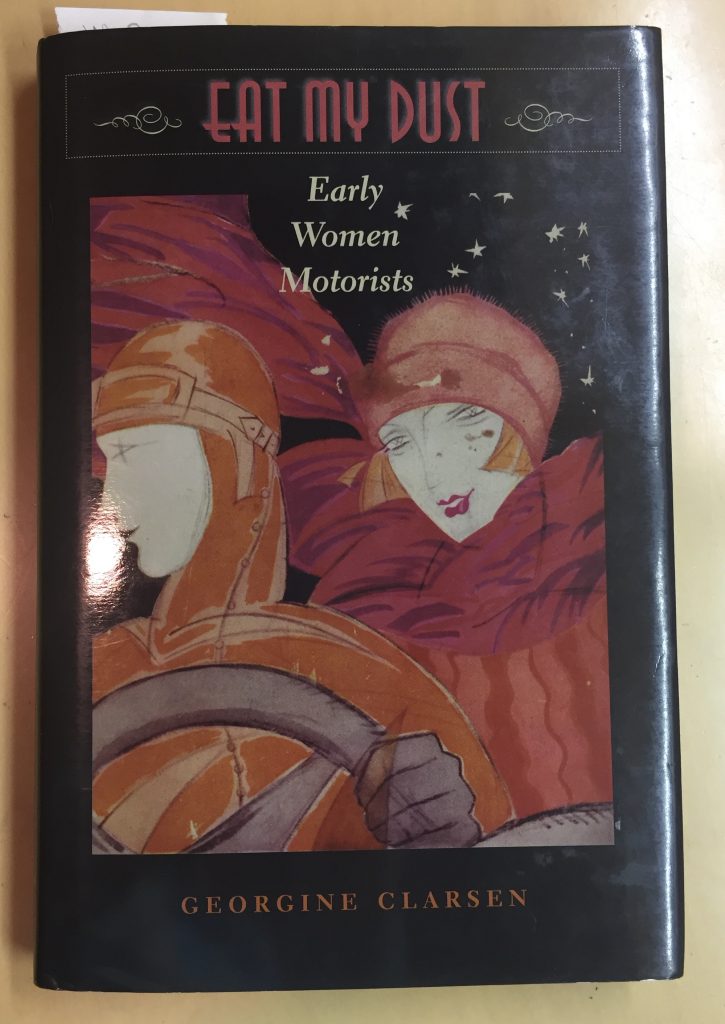

Growing up in Detroit, I often thought of interest in automotive history as a particularly American, if not Southeastern Michigan, phenomenon. As a young adult, working in an automotive advertising agency, surrounded by a plethora of male auto aficionados, I assumed this enthusiasm for all things automotive was most often framed by gender and geography. Imagine my surprise, therefore, when beginning my research on women and cars, I discovered that two of the more prominent and prolific historians of the female motorist were neither male nor American. Margaret Walsh, a historian at the University of Nottingham in the UK, who I have written about in an earlier blog, and Georgine Clarsen, a scholar of history at the University of Wollongong in Australia, have individually and independently made considerable contributions to the women’s automotive history archives. While Walsh’s work focuses primarily on the history of the woman driver in the United States, Clarsen’s major work – Eat My Dust: Early Women Motorists – explores women’s active roles in shaping automobile culture in her native Australia, Britain, British colonial Africa, as well as the USA. Her most recent research – as noted in The Conversation – specifically examines early around-Australia automobile journeys and the role of automobility in shaping ideas of colonial settler landscapes and identities. While much of her scholarship is centered on the automobile, Clarsen has also written extensively on women’s mobilities in other modes of transportation, such as bicycles and buses.

As both a historian and a feminist, Clarsen is interested not only on the specifics of women’s early automobility, but also how automotive narratives were often called upon to frame sexual difference, bodily experience, and identity. Considering the countless histories generated since the automobile’s inception, Clarsen writes, “Histories of automobiles […] are more than they seem. Like all histories, they exceed their avowed subject matter to tell a great more besides. Beyond their manifest concerns, they provide a dense array of metaphors, images and progressions through which other stories have been told” (Dainty 153). Clarsen’s extensive scholarship is valuable not only as a source of knowledge regarding the early woman driver, but also calls upon women’s relationship to the automobile to frame debates about class, gender, sexuality, race, and nation in a variety of locations.

In my own work, I found Clarsen’s writing invaluable in discussions regarding the woman driver stereotype and how women – throughout automotive history – have been routinely dismissed as unknowledgeable about cars, uninterested in automobile technology, and inept as drivers. While I am not a historian, automobile/mobility scholars such as Clarsen have both informed my work and served as inspiration into my research devoted to the subject of women and cars.

Clarsen, Georgine. “The ‘Dainty Female Toe’ and the ‘Brawny Male Arm’: Conceptions of Bodies and Power in Automobile Technology.” Australian Feminist Studies 15.32 (2000): 153-163.