A popular and sometimes irreverent automotive website, Jalopnik not only produces timely car-related articles, but it often gets readers involved by asking for input on various autocentric topics. One of the subjects covered recently was that of car stereotypes. After the author presented a few of his own, the article was followed up by responses from Jalopnik readers. The collected list of stereotypes ranged from the odd and obscure to the well-worn. Among those offered: Miatas are favored by gays; Subarus are driven by lesbians; pickups are the choice of rednecks; muscle cars are owned by macho men; Corvettes are the pick of old guys; Buicks are the car of choice of anyone over 80. What is interesting about these common and oft cited stereotypes is how intricately they are intertwined with gender. Gender, sometimes combined with sexual orientation or age, is not only the major identifier of the car owner, but is the primary means by which a vehicle is disparaged or valued.

This should not be surprising. Gender in car culture is often called upon to ascribe value and authenticity or to degrade and diminish a particular automobile. Due to the automobile’s longstanding association with masculinity, vehicles strongly associated with the youngish straight [white] male driver are invariably considered more powerful, better engineered, technologically superior, more responsive, and of greater workmanship and quality than those chosen by women or members of the LBGTQ community. Much of this assumption is based on the common perception that women just don’t know much about cars. As historian Judy Wajcman notes, “the absence of technical confidence or competence does indeed become part of feminine gender identity, as well as being a sexual stereotype” (155). The belief that women lack technical expertise often creates a reverse kind of logic in the minds of many male consumers. They believe that since women cannot appreciate the finer technical characteristics of a car, such as power, handling, and performance, the cars women purchase must be deficient. Women’s approval, in the minds of many men, leads to the devaluation of the car.

This assumption of automotive inferiority carries over to cars popular in the gay community. In Masculinities, RW Connell remarks that the common perception of gay men is that they “lack masculinity”. As Connell writes, “from the point of view of hegemonic masculinity, gayness is easily assimilated to femininity” (78). Because gay men are often considered feminine among the straight-white-male population, the automobiles they drive are marked “girly’” as well. Consequently, vehicles marked as feminine or “gay” are thought of as less, affecting automotive sales and discouraging those buyers who wouldn’t be caught dead driving a “feminine” car.

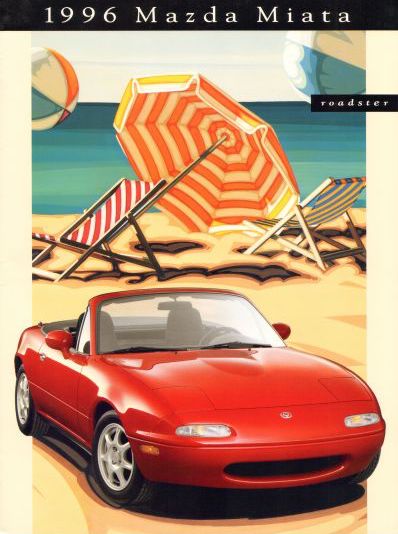

What is interesting is that the cars subject to disparaging gender stereotypes were not, for the most part, originally produced or marketed to non-straight-white-male customers. As an example, vehicles now labeled “chick cars” are fast, sporty, nimble vehicles originally produced for the male automotive enthusiast. However, once women with car savvy and newly acquired spending power appropriated the Miata, VW New Beetle, and Mini Cooper as their own, many members of the male population became hesitant to drive them. Some men consider the “chick car” an affront to their masculinity and fear what driving such a car will say about them. As auto writer Ted Laturnus suggests, “for a lot of male drivers, the thought of driving a ‘chick car’ is the kiss of death when it comes to signing on the dotted line.”

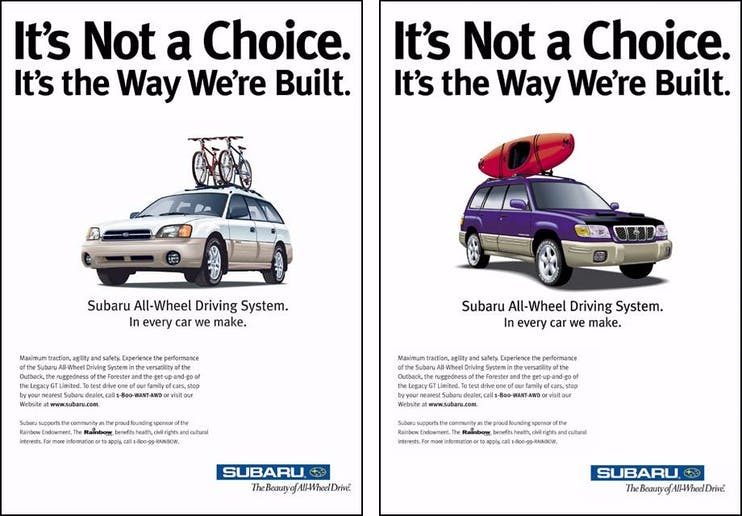

The same could be said for the Subaru. As noted on its website, “Subaru has a long history of offering vehicles that are both highly capable and intelligently designed.” Originally known for its 4WD station wagon, the introduction of the Outback SUV – the first of its kind in the automotive industry – led to Subaru’s reputation as a manufacturer of safe and practical vehicles with exceptional performance features. While originally marketed as a vehicle for outdoorsy adventurous guys as well as active families, the Subaru is now considered a top choice for those who identify as lesbian. Yet unlike the chick car scenario, in which automakers beefed up the Beetles and Mini Coopers to make them more appealing to men, Subaru actively and aggressively pursued the lesbian market. As Alex Mayyasi reflects, ‘the marketers found that lesbian Subaru owners liked that the cars were good for outdoor trips, and that they were good for hauling stuff without being as large as a truck or SUV. (In a line some women may not like as much, marketers also said Subaru’s dependability was a good fit for lesbians since they didn’t have a man who could fix car problems.)” Yet unlike chick car manufacturers who feared an association with the woman driver would affect automotive sales, Subaru was confident enough in its product to aggressively pursue the lesbian market. Although the Subaru remains a popular choice among teachers and educators, health care professionals, IT professionals, and outdoorsy types of all genders and sexual orientations, its appeal to the non-straight-white-male population has led to its label as the “lesbian” car.

The age group of a certain automotive purchaser also contributes to a negative stereotype. Older drivers are considered overly cautious, accident prone, and focused on amenities that contribute to a vehicle’s safety, comfort, and economy rather than handling, power and performance. Consequently, car models favored by senior citizens are considered less desirable than those marketed to young white men. Despite its current advertising campaign, Buick’s long association with mature drivers has stubbornly labeled it as the old person’s car.

In much of my research, I focus on women who drive vehicles that challenge gender stereotypes by choosing vehicles – muscle cars, chick cars, and pickup trucks – associated with men. These women often face disparaging remarks and unsubstantiated assumptions regarding their vehicle choices. Although the most prevalent car stereotypes are those associated with femininity, women who choose ‘masculine’ vehicles are not immune.

While car stereotypes are not universally focused on gender, the fact that so many rely on the notion that vehicles associated with individuals who are not young, white, straight, and male are worthy of ridicule is telling. While the intention of the Jalopnik article no doubt was to engage and entertain its readers, it also reminds us that at least in the car world, as Virginia Scharff writes, “what is seen as feminine, or belonging to women, seems trivial at best, dangerous at worst” (167).

Bellwood, Owen. “What Car Comes with the Weirdest Stereotypes?” Jalopnik.com 16 Nov 2021.

Connell, R.W. Masculinities. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

“The History of Subaru.” grandsubaru.com

Laturnus, Ted. “So What’s Not to Like About a So-Called Chick Car?” Globe and Mail. 19 Jan. 2006.

Mayyasi, Alex. “How an Ad Campaign Made Lesbians Fall in Love with Subaru.” lesbianbusinesscommunity.com n.d.

Scharff, Virginia. Taking the Wheel: Women and the Coming of the Motor Age. Albuquerque: U of New Mexico P, 1991.

Wajcman, Judy. Feminism Confronts Technology. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1996.