The Wills Sainte Claire Auto Museum is a small museum located in the out-of-the-way city of Marysville, Michigan, separated from Canada by the St. Clair River. It is devoted to the history of C. Harold Wills and the automobile he created – the Wills Sainte Claire – and their impact on auto history and the city of Marysville. The small building holds 20 Sainte Claire automobiles – the largest collection in the world – as well as original photos, color advertising, and other artifacts relating to the company’s brief history. The automobiles on display are include ‘survivors’ as well many that are impeccably restored. The museum is only open one Sunday afternoon a month; our visit included a short video as well as peek behind the scenes into the museum’s storage facility.

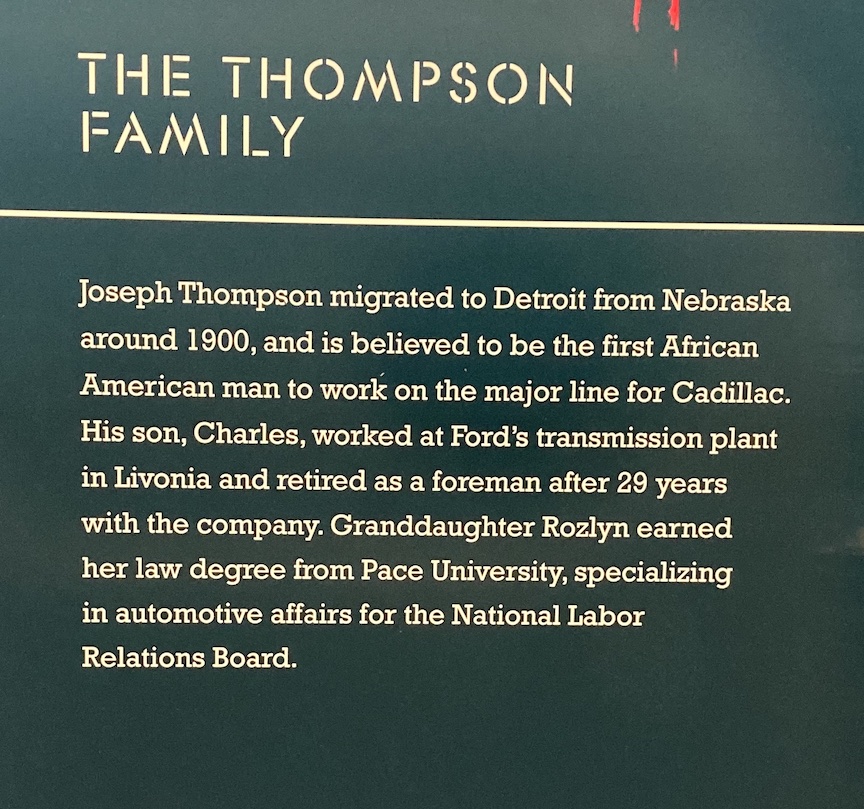

C. Harold Wills was Henry Ford’s first employee. He served as chief designer and metallurgist; he was responsible for the design of the Ford script logo, still in use today. Wills desperately wanted to make changes at Ford; unable to do so he left the company – with his $1.5 million severance pay – to build a car in Marysville along the banks of the St. Clair River. His plans also included a housing development – the “City of Contented Living” – for Sainte Claire employees.

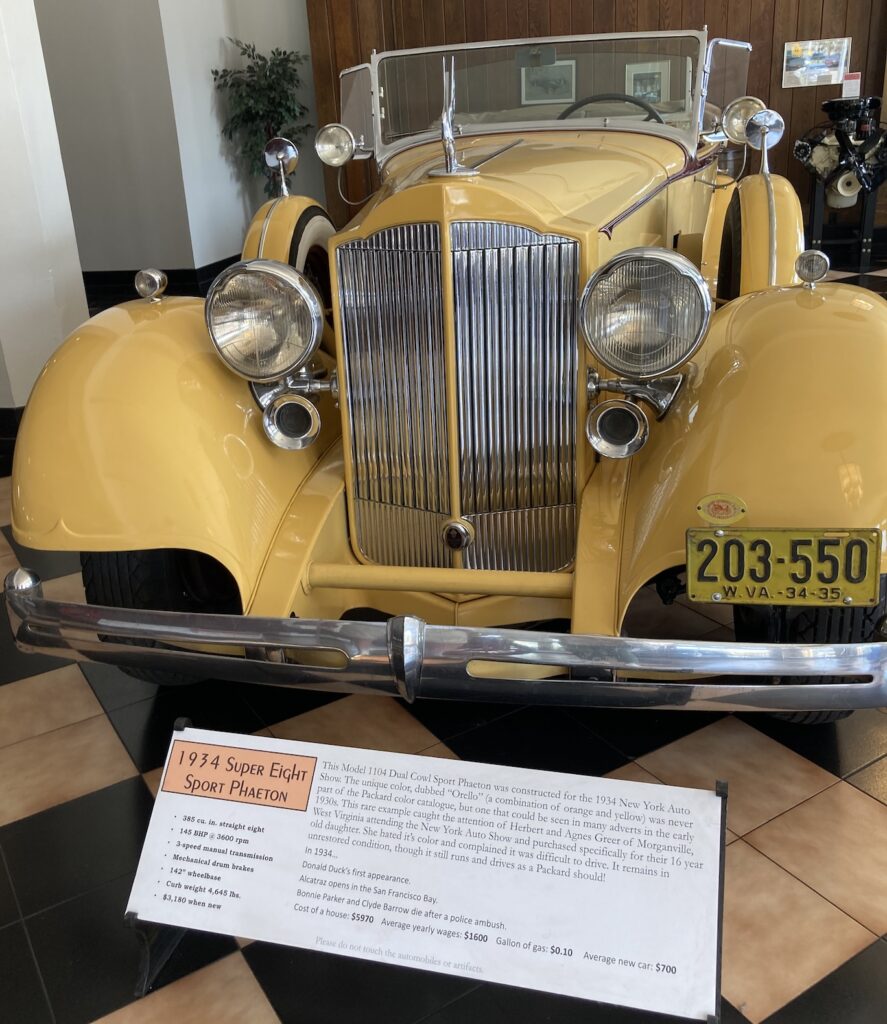

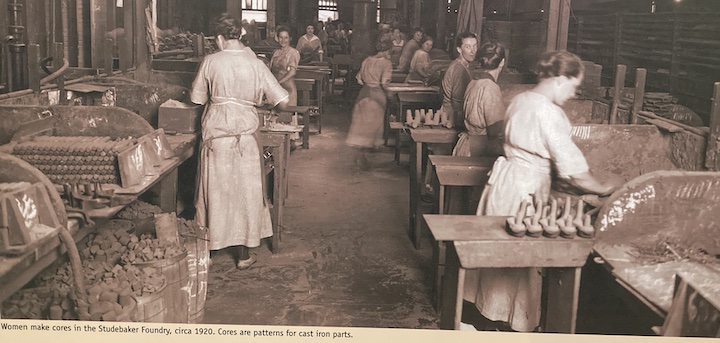

The automobile Wills envisioned was the polar opposite of Ford’s affordable, mass-produced, Model T; rather, it was a somewhat futuristic vehicle that used state of the art engineering concepts and materials. He hoped to compete with luxury automakers such as Packard, Lincoln, and Pierce Arrow. The first car rolled off the assembly line in the spring of 1921, by November 1922, the Wills Co. was $8 million in debt and forced into receivership. Although beautifully crafted and ahead of its time, the car did not do well. It was too expensive, and Wills continually interrupted production to implement every conceivable improvement. The company did not survive the 1926 recession and after producing 12,000 cars, was liquidated. Wills subsequently joined Chrysler as a metallurgical consultant; Chrysler purchased the former Wills Sainte Claire factory which is still in use today.

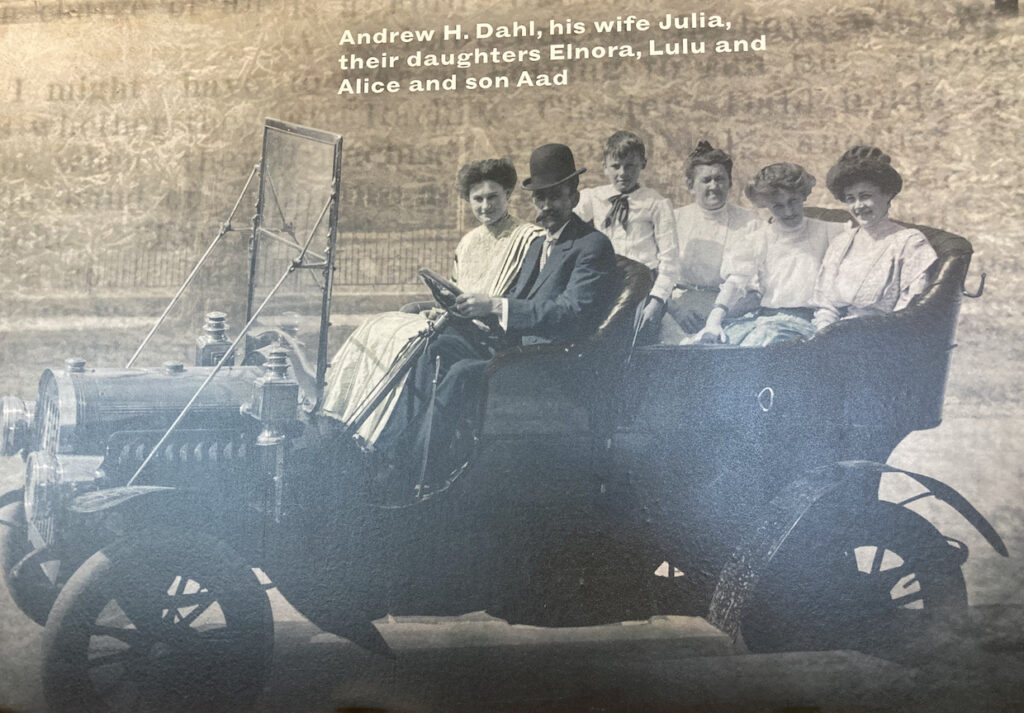

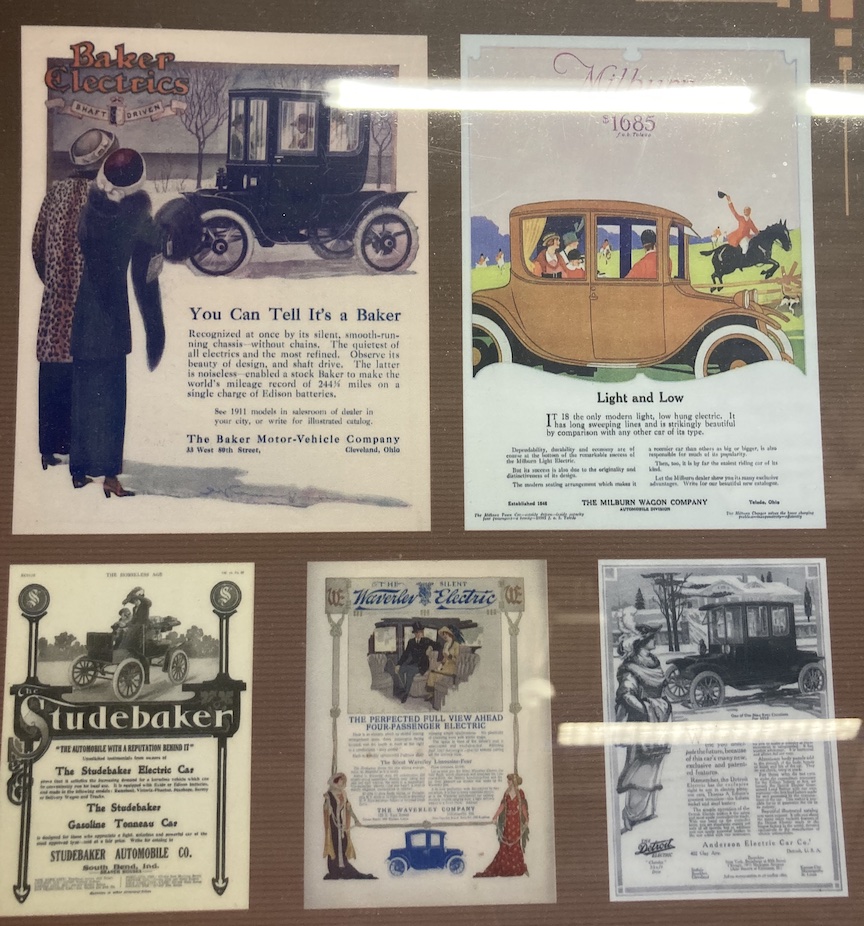

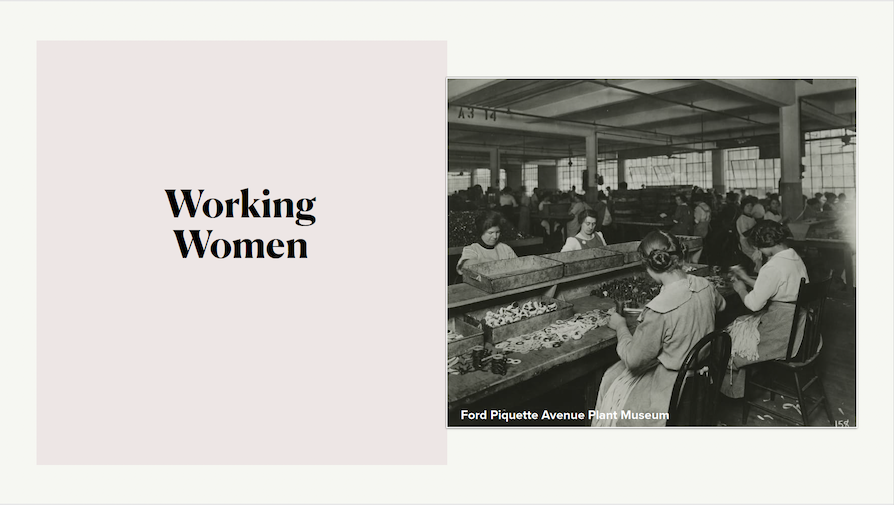

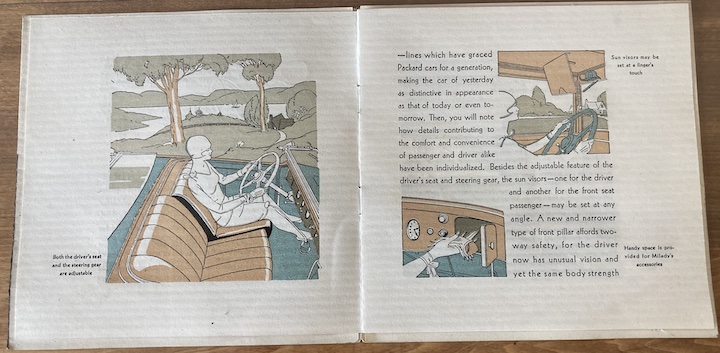

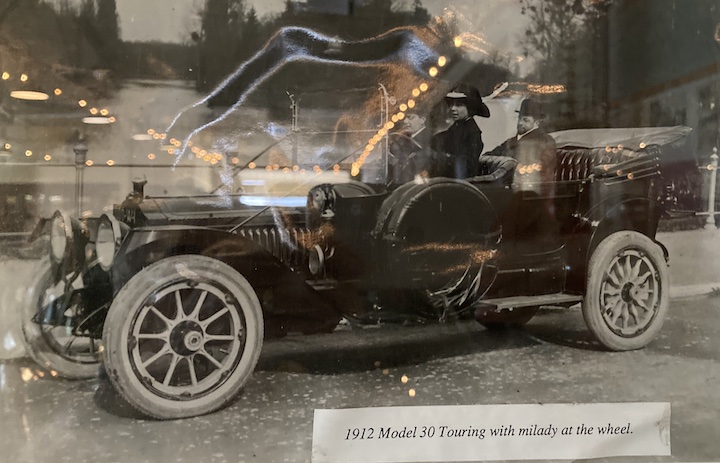

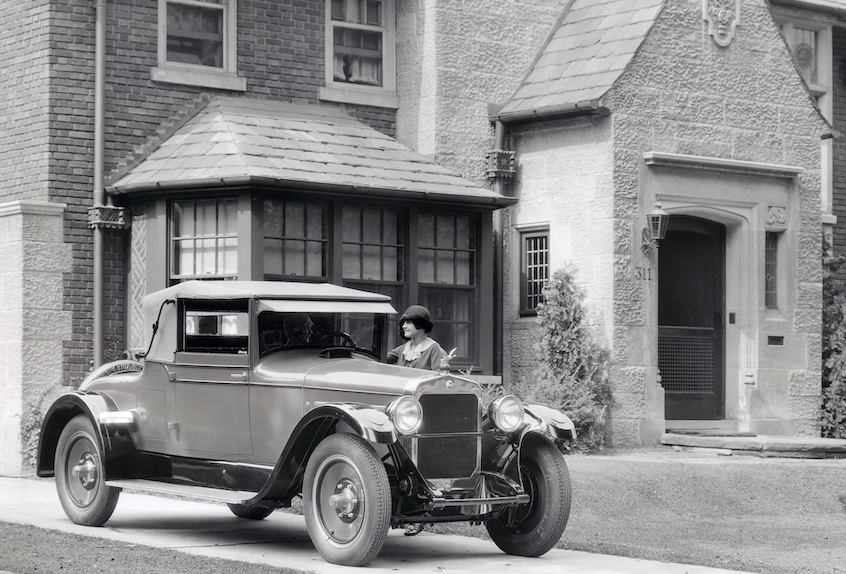

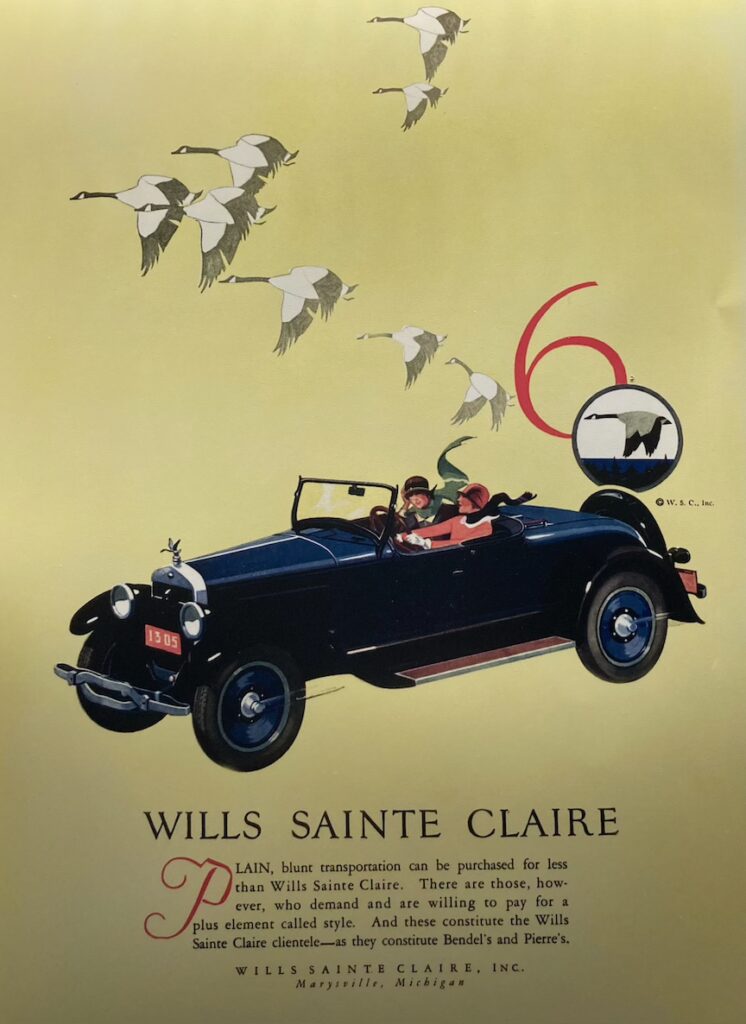

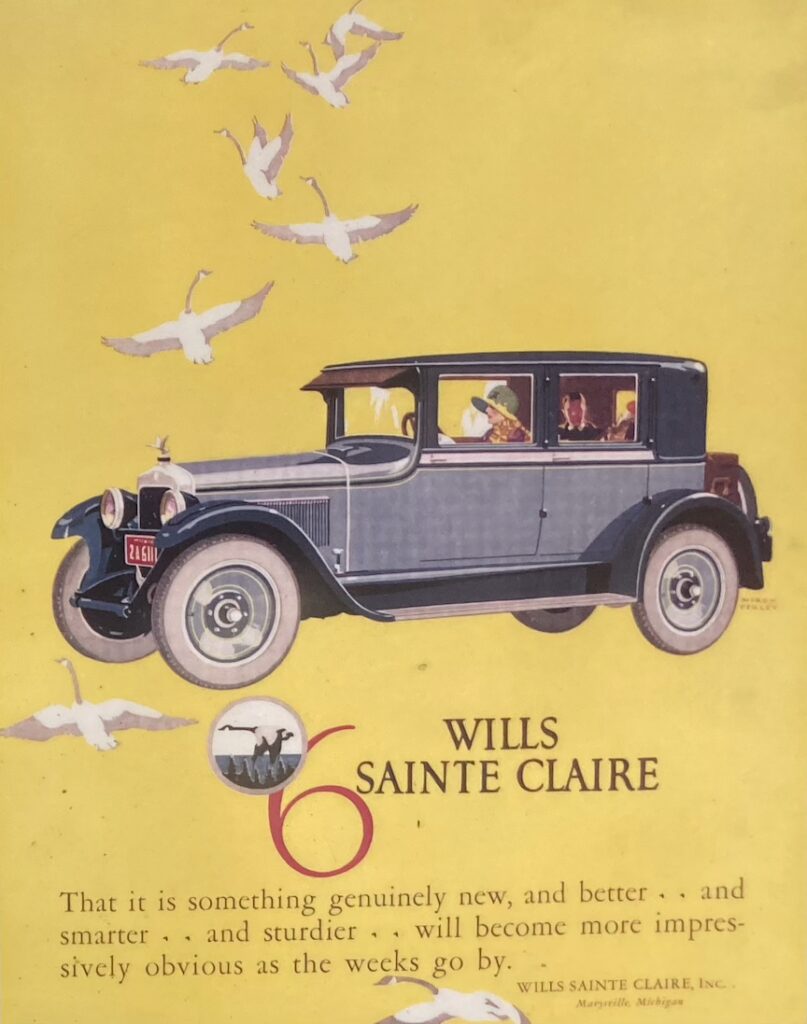

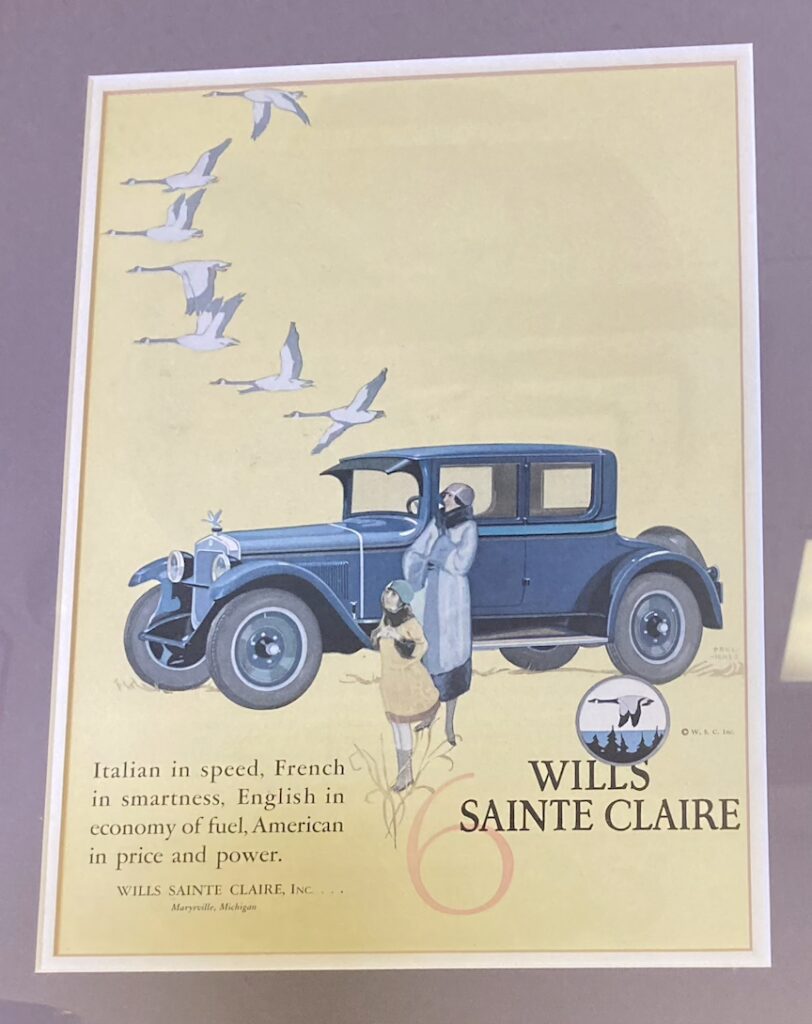

Throughout its short history, Wills Sainte Claire advertised extensively, always promoting the automobile’s luxury. As one advertisement read, “How can classic be defined? Sleek, stylish, perfection, unique, timeless, and valuable are words of articulate, lasting design. If you assemble these words in the form of a tangible object you have defined the unique and beautiful Wills Ste. Claire automobile.” What is unusual for this time period is that many of the advertisements – on display at the museum – feature women behind the wheel.

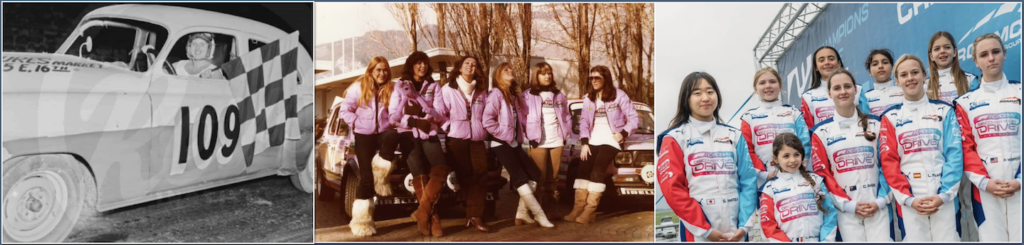

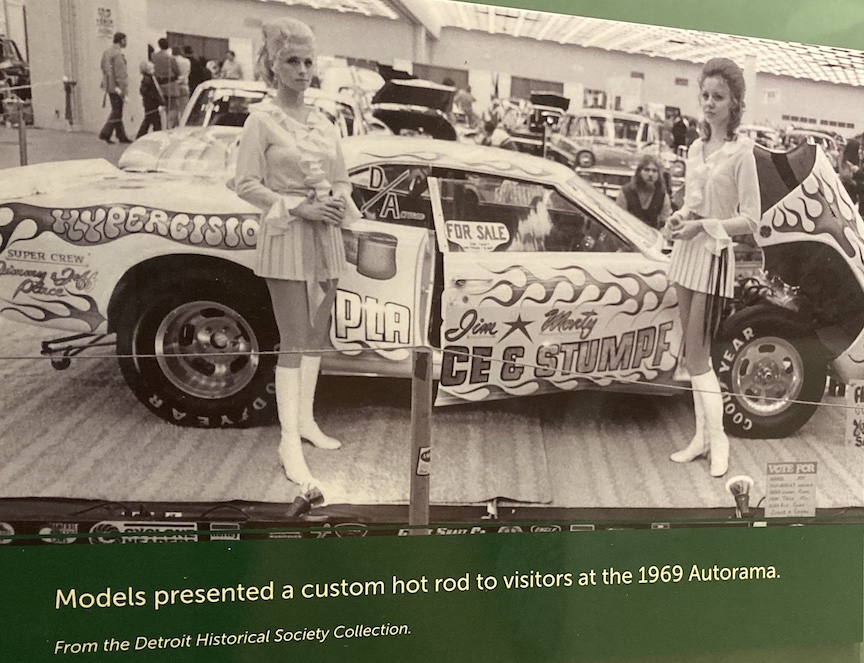

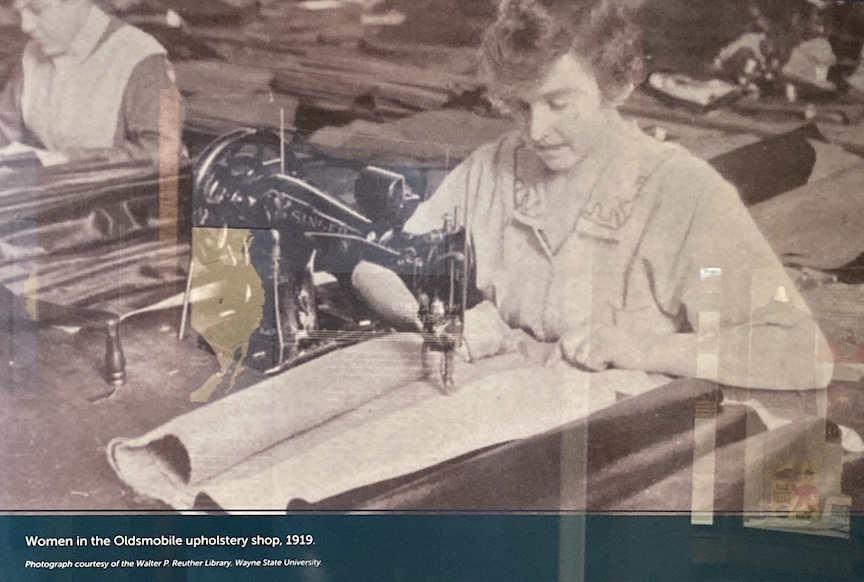

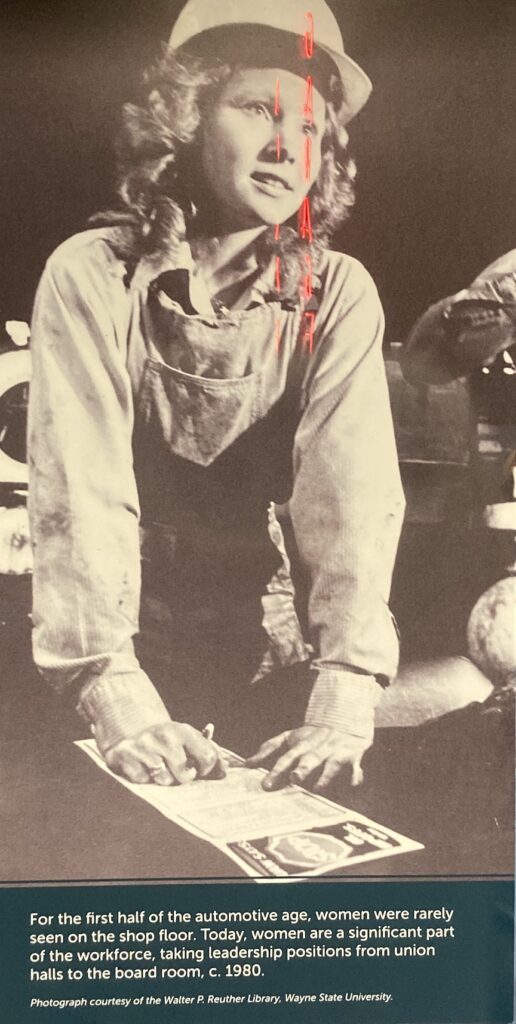

As women rejected the electric automobile in favor of the faster and more affordable gasoline-powered car, automakers – recognizing a growing consumer base – developed strategies to lure the female driver. Marketing plans shifted from “discussing merits of products to constructing promises for, and listing the expectations of, those who consumed the products.”[1] Relying on the rise in readership of popular women’s magazines, one of the more prominent sales tactics to emerge was advertising that “invited women to seek social status via the purchase of an automobile.”[2]

Wills Sainte Claire wholly embraced this strategy in its advertising. As a 1926 advertisement in the Saturday Evening Post read, “plain, blunt transportation can be purchased for less than Wills Sainte Claire. There are those, however, who demand and are willing to pay for a plus element called style. And these constitute the Sainte Claire clientele – as they constitute Bendel’s and Pierre’s.” The ad includes an illustration of two fashionably attired women travelling – with scarves flying – in a bright red Wills Sainte Claire roadster. An ad published in National Geographic, accompanied by an illustration featuring a woman seated in the driver’s seat with two children behind her, informs its female audience that the 1926 Model T-6 5-Passenger Sedan, “is something genuinely new, and better…and smarter…and sturdier… will become more impressively obvious as the weeks go by.”

The strategies employed by auto advertisers were constructed, in part, as a response to Ford’s early domination of the automotive market. By 1921, Ford produced over half of all cars in the world. Fords were not only plentiful, but affordable; “growing cheaper by year, the Model T opened new vistas for ordinary people,” which included the growing population of women drivers.[3] Unable to compete head-to-head with “Everyman’s [and Everywoman’s] Car,” manufacturers set out to distinguish their automotive offerings by including an intangible benefit – status – with vehicle purchase. As Ford’s dominance began to erode – due primarily to the company’s unwillingness to move on from the Model T – the automobile as representative of women’s social standing became a popular, effective, and longstanding strategy among luxury cars manufacturers.

Unfortunately for the Wills Sainte Claire, the association of the automobile and social status was not enough to save it. However, the advertising of this little known manufacturer – on display at this small museum on the Michigan-Canadian border, provides insight into the efforts of luxury auto manufacturers to attract the female consumer.

[1] Michelle Ramsey. “Selling Social Status: Woman and Automobile Advertisements from 1910-1920.” Women and Language 28(1) Spring 2005: 26.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Virginia Scharff, Taking the Wheel: Women and the Coming of the Motor Age (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1991), 55.