Curbside Classic promotes itself as collector of automotive stories. Relying on contributions from its subscribers, the online publication assembles donated photographs of classic cars to construct “a living time capsule of collective knowledge, experiences, and history.”

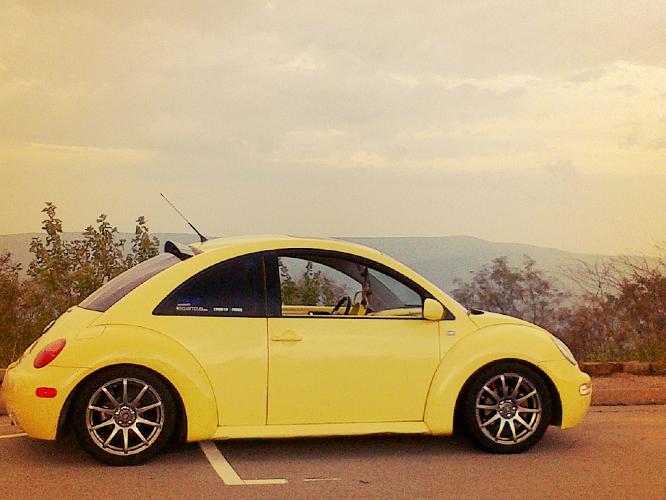

[Curbside Classics photo]

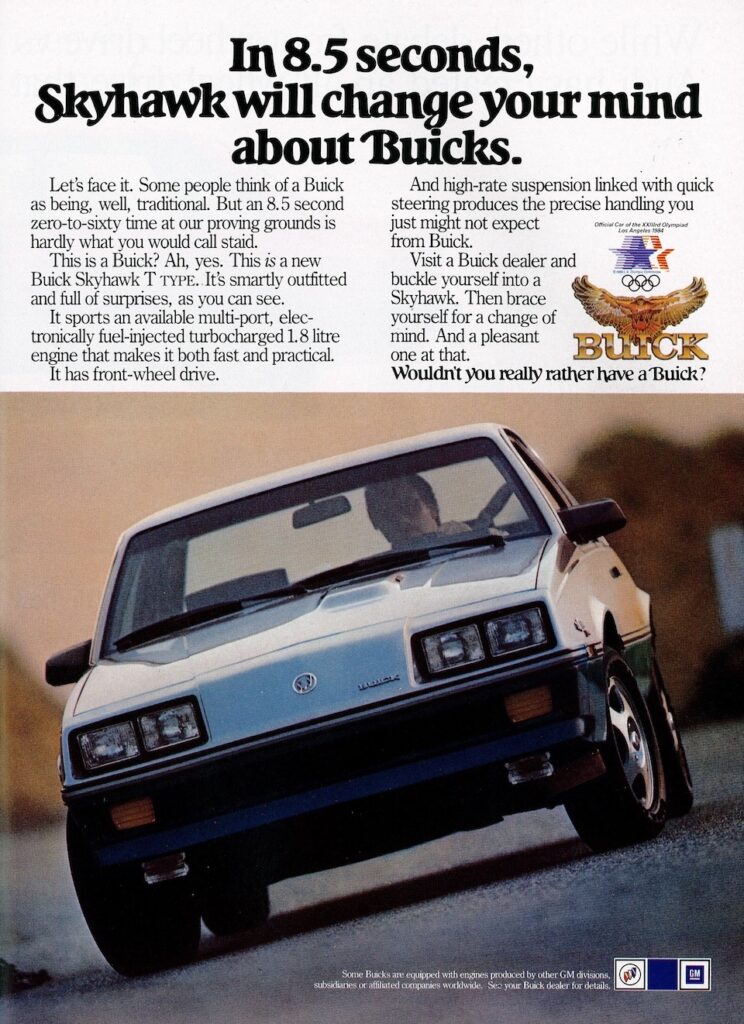

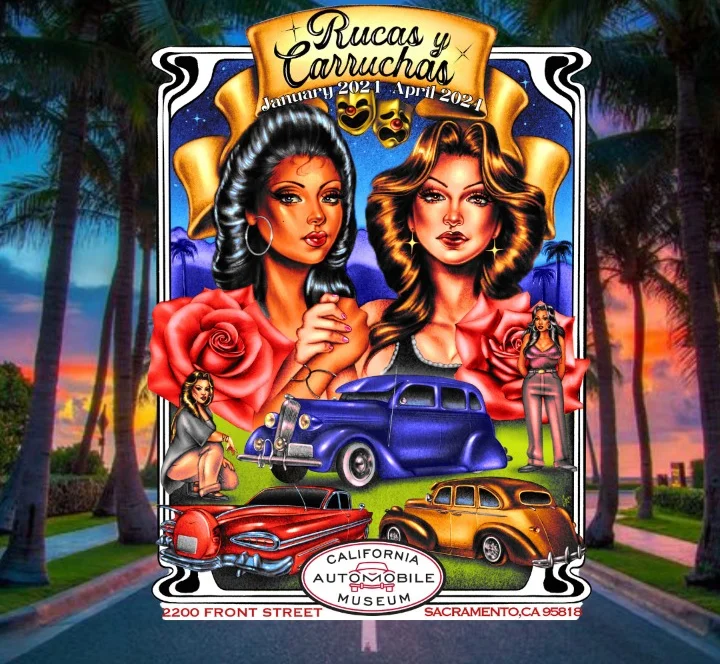

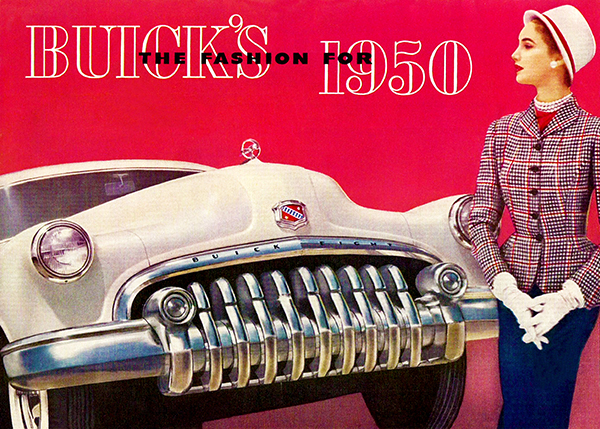

A Curbside Classics story that recently caught my eye was titled ‘Ladies and Buicks: 1950s Style.’ It included a number of photos of well-dressed suburban women posed next to their Roadmasters, Rivieras, Centurys, and Special Deluxe Tourback sedans. As one who worked on the Buick account during the mid-eighties, with the assignment to reconfigure the Regal into the ‘women’s car,’ I was intrigued by how – 30 years earlier – women had claimed the ‘doctor’s car’ as their own.

During the 1950s, Buick’s primary market was the aspiring middle and upper-middle class American consumer. Positioned in the General Motors lineup just one rung below the luxurious Cadillac, Buick was an attractive choice for professionals, managers, and business owners. Symbolizing success without ostentation, Buick appealed to doctors, lawyers, executives, and mid-level corporate managers.

[Curbside Classics photo]

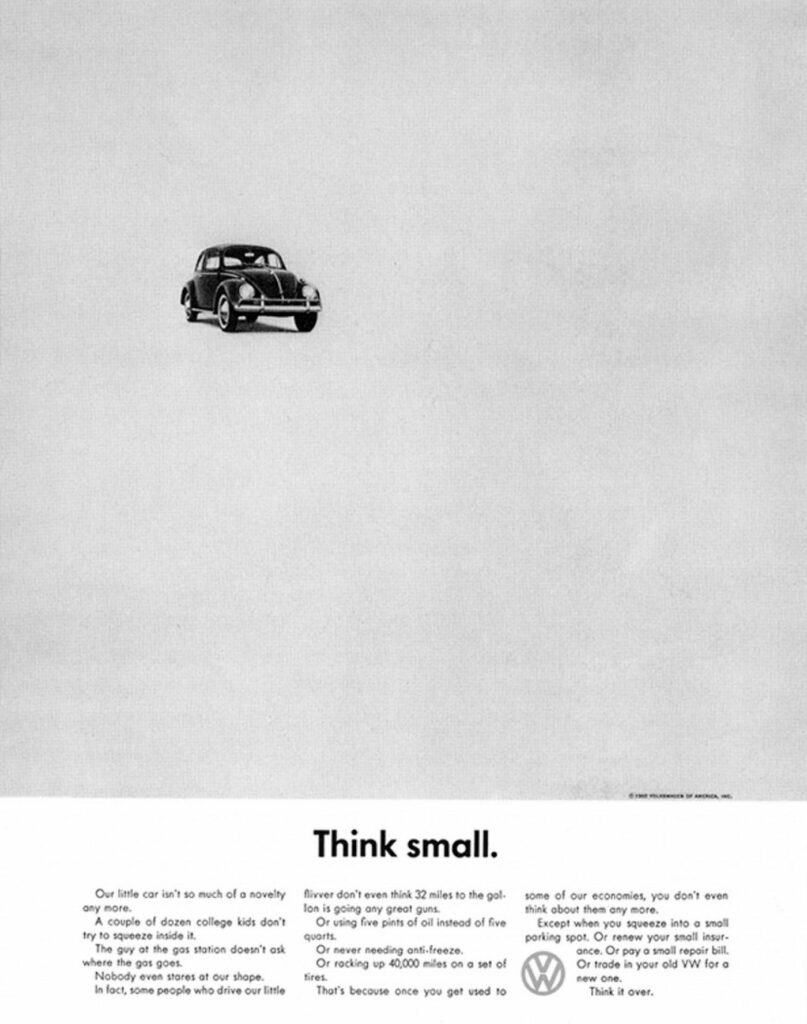

While Buick advertising most often centered on the male breadwinner, it increasingly acknowledged women as influential decision makers in the home, particularly where budgets were concerned. The move to the suburbs in the post war era resulted in the increased presence of women behind the wheel. Consequently, automakers promoted automotive features they believed were important to women drivers, such as automatic transmissions, power steering, and power brakes. These features were often framed as making the car easier and more comfortable for the woman driver. Advertising marketed toward men, on the other hand, was more likely to emphasize power and performance.

The ladies pictured alongside their Buicks in the Curbside Classic story are fashionably dressed, often in outfits that complement the car. The relationship between automobiles and fashion in these photographs is not just a coincidence; during the 1950s, women’s fashion was an important influence on automotive design. As Richard Martin argues, “Not only were the ideas expressed in these two arts [fashion and auto design] alike, so, too was the very timing of the style changes.”

[Curbside Classics photo]

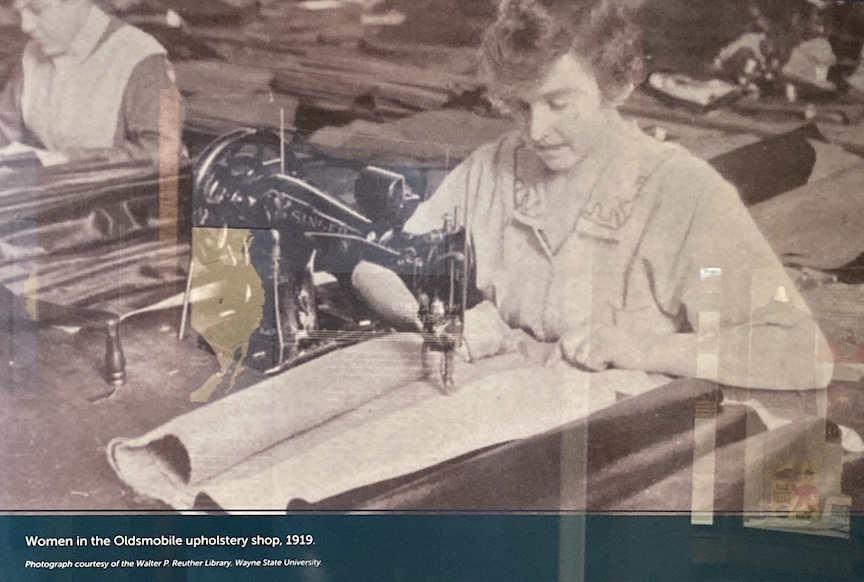

Harley Earl, widely considered the father of modern automotive design, fundamentally transformed automotive styling in the United States. Employed by General Motors from the late 1920s to the 1950s, Earl elevated styling from a secondary consideration to a central driver of automobile sales and brand identity. The GM Art and Colour Section, established by Earl in 1927, was the first formal automotive design studio in the industry. Color was placed alongside form as a core element of vehicle design. Paint was planned simultaneously with body styling, rather than applied after engineering decisions. Designers – much like those in the fashion and interior design industries – studied color harmony, fashion trends, and consumer tastes. And while Earl was perhaps best known for his influence on exterior styling, as Hemmings writer David Conwell notes, “the designer replaced the engineer on the inside as well.” Interiors, upholstery, dashboard finishes, and exterior paint were coordinated into complete color schemes. In essence, Earl helped establish the idea that color could shape how a car looked, how it expressed status, and how consumers connected with it emotionally. Paint schemes became tools for emphasizing form, communicating brand identity, and encouraging consumers to view the automobile as a fashionable object. Earl was the first to employ female designers – referred to as the “Damsels of Design” – to shift the automotive focus from purely mechanical performance to [female] user experience and aesthetics.

As historian Robert Tate asserts, during the 1950s, “automakers observed that fashionable colors and accessories were bringing more women into dealerships.” Thus automotive color design – shaped in part by the styling practices of designers such as Earl – became closely tied to gendered marketing strategies. Postwar cars were often produced in pastels and fashion-inspired colors; advertising often implied these colors would appeal to women because they resembled fashion palettes, harmonized with suburban homes and lifestyles, and softened the car’s mechanical image. As automakers acknowledged women’s influence in consumer decisions, 1950s advertising encouraged women to view the car not just as transportation, but as another designed element of the modern household.

[Curbside Classics photo]

The photographs in the Curbside Classic collection demonstrate the influence of women’s fashion on automotive style. They also reflect how women, pleased with their automotive choices, often clothed themselves in coordinating ensembles to express their newfound relationship with the car.

Baron, Rich. “Ladies and Buicks: 1950s Style in Vintage Photos.” curbsideclassics.com Feb 26, 2026.

Conwill, David. “GM’s Art & Colour Section Put Interiors Front and Center” hemmings.com July 3, 2024.

Martin, Richard. “Fashion and the Car in the 1950s.” Journal of American Culture 20 (3) Fall 1997.

Tate, Robert. “The Influence of Women Consumers on Automotive Design” Motorcities.org March 22, 2023.