While working on my master’s degree at Eastern Michigan University in the early 2000s, I devised an independent study focused on my growing interest in the relationship between women and cars. What follows is one of the response papers in which I consider how men and women often have different perspectives regarding tourism, travel, and romantic encounters in automobiles.

There can be little argument that social and historical accounts of American car culture are often romanticized, both figuratively and literally. Such sentiments are certainly evident in discussions of the automobile’s role in leisure and recreation, which include the topics of travel, tourism, courtship, and sex. Contemporary cultural commentators often examine the car as a location for both families and lovers in a quixotic and lighthearted manner. Warren Belasco, for example, suggests the “erotic excitement” of “auto camping” not only served as an “aphrodisiac,” but also as “a new companionate family ideal” that brought families together (107). James Flink praises the “family automobile vacation” as a middle-class American institution. As it spawned popular motel chains and iconic drive-in restaurants along America’s roadways, the automobile, Flink argues, became an essential contributor to the travel industry and the American economy. Lewis remarks that, even more than a mode of transportation, cars evolved into “a destination as well, for they provided a setting for sexual relations […]” (123). The car as a symbol of sexual prowess, as well as a location for sexual practice, is often celebrated by car culture pundits. As Julian Pettifer and Nigel Turner attest, “for the young male in the US, the car is an absolute essential for successful courtship” (194). And in his 1973 film American Graffiti, George Lucas examines the role of the automobile as both a social and sexual space with nostalgia and humor. However, such romanticized notions of the car in American culture do not tell the whole story. While they provide a familiar narrative, they do so in a way that is decidedly and overwhelmingly male.

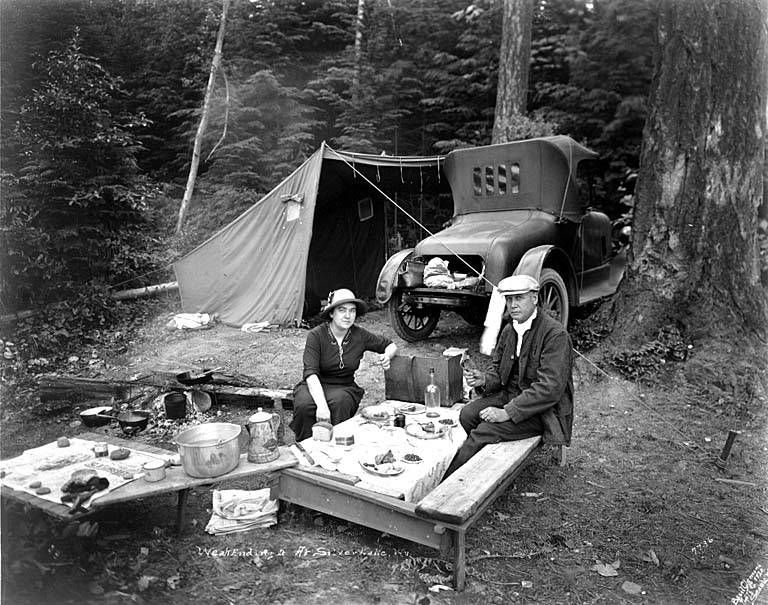

Most commentaries present the American car culture experience as uniform and universal. However, women’s place in car culture differs remarkably from that of men. During the first half of the twentieth century, the majority of men perceived auto camping as unconventional, adventurous and exciting. There can be little doubt that many of them also considered it a welcome and necessary respite from everyday responsibilities. While a woman may have enjoyed such occasions of enforced family “togetherness,” her domestic responsibilities, whether in the home or in the car, remained the same. As travel writer Zephine Humphrey penned in 1936, “the burden of home life was discarded, but the essence of it we had with us in the four walls of the car” (Sanger 728). While on the road, women were still responsible for household domestic tasks, albeit in a much more primitive setting. Belasco writes, “roadside camping was too difficult for many, especially for women, whose participation was essential in a family-oriented activity” (113). Women’s performance of domestic tasks on the road, as it was in the home, was assumed and expected. The implication, therefore, is that women’s “difficulty” is based on a lack of creature comforts rather than added domestic responsibilities. In fact, Flink attributes the “spectacular” growth of the camping equipment industry to the need of such “comfort-conscious” women for “large tents, folding cots with springs, air mattresses, portable gas stoves and lamps, and elaborate yet compact kits of kitchen utensils” (183). While auto camping may have been perceived, as Belasco writes, as a “chance to leave the crowd,” women were unable to leave their domestic responsibilities behind. Thus their experience of auto camping differed considerably from that of men.

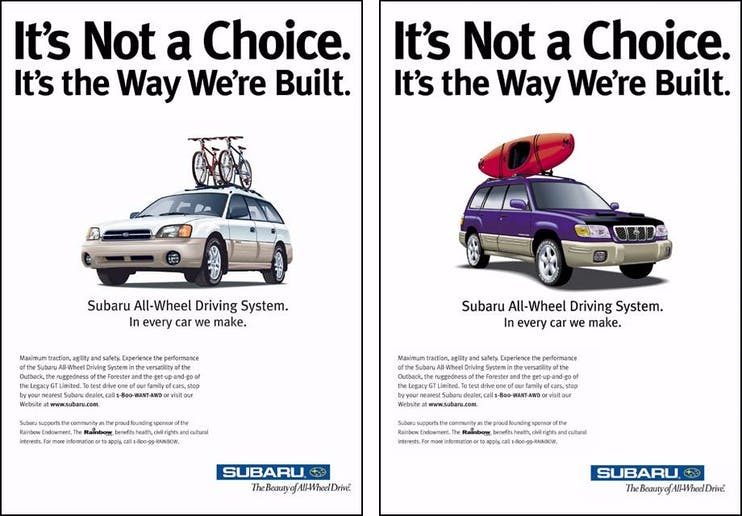

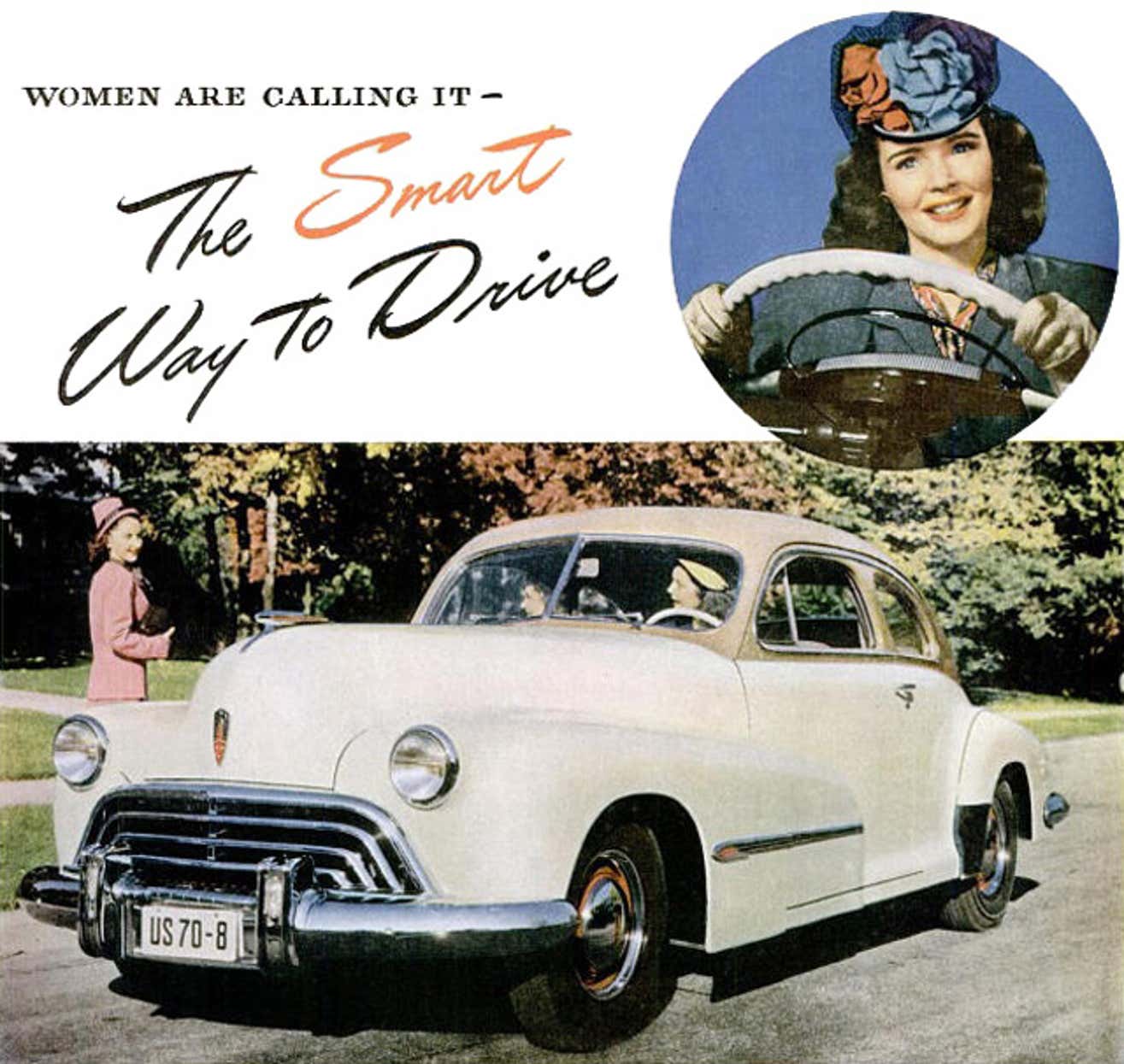

In “Girls and the Getaway,” Carol Sanger writes, “the car has reinforced women’s subordinated status in ways that make the subordination seem ordinary, even logical through two predictable, but subtle, mechanisms: by increasing women’s domestic obligations and by sexualizing the relation between women and cars” (707). While motels and gas prices have contributed to a decline in auto camping and the domestic responsibilities that accompany it, women are still expected to use cars for the performance of gendered tasks. The woman’s automobile is considered a form of domestic technology; man’s car, on the other hand, is often a symbol of power, control and sexual prowess. As Pettifer and Turner state, “a man is very affectionate towards his car, he gets into his car he switches on the power; he then has almost a passionate relationship and a passionate satisfaction out of controlling the power to the car” (188). Not only do men call on cars as a source of identity, but use them as a means to assert control over women. Thus while Lewis and Lucas may fondly reminisce about the joy of having sex in cars, “because they found it exciting, sometimes dangerously so, and a change from familiar surroundings” (124), for many women, “riding in cars with boys” has a very different meaning.

Lewis is correct when he suggests that the car offered young men and women the opportunity for consensual sex. And certainly there have been many women who have engaged in such practices openly and willingly. As Sanger writes, “this intimate realm of vehicular privacy is sometimes good. Couples may want to share unscrutinized moments; the car has been reported as the most common site for marriage proposals” (731). However, getting into a car or offering a ride to a man often implies consent when none is present. And because cars provide a “male-controlled” privacy, they are common sites for sexual assaults. Lucas addresses this in a humorous, yet all too familiar way in American Graffiti. As Steve Belanger is about to leave for college, he asks his girlfriend Laurie to “give me something to remember you by.” Laurie responds by kicking him out of the car. However, it is Laurie’s car; if the incident took place in Steve’s “male-controlled” space, most likely there would have been a very different (and considerably less funny) outcome.

While often informative, educational and entertaining, most accounts of American car culture are constructed from a male perspective. When women are present, they are most often presented in a secondary, if not subservient role. While the work of contemporary cultural commentaries are valuable, women’s contribution to car culture in such contexts is often distorted to fit male paradigms. What such accounts suggest, and encourage, however, is that more work is needed in order to accurately and objectively uncover women’s place in American car culture.

Belasco, Warren. “Commercialized Nostalgia: The Origins of the Roadside Strip” in The Automobile and American Culture, David L. Lewis and Laurence Goldstein eds. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1983.

Flink, James. The Automobile Age. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 1990.

Lewis, David. “Sex and the Automobile” in The Automobile and American Culture, David L. Lewis and Laurence Goldstein eds. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1983.

Pettifer, Julian and Nigel Turner. Automania: Man and the Motor Car. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1984.

Sanger, Carol. “Girls and the Getaway: Cars, Culture, and the Predicament of Gendered Space.” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 144.2 (1997): 705-756.