To the majority of folks, Jay Leno is a former stand-up comic who had a very nice 20-plus year run as host of The Tonight Show. However in automotive circles, Leno is recognized for a very different television offering. Since 2015, Leno has used his celebrity status to encourage interest in automotive history through “Jay Leno’s Garage,” the Emmy winning series in which Leno offers car reviews, automotive tips, and shares his automotive passion and expertise through his extensive and expensive collection of automobiles. Viewers to his show are treated to test drives of vehicles of every persuasion, from the common to the obscure, powerful to mundane, excessive to pedestrian. However, as noted in a recent article in The Drive, there is one automotive model that is notably absent from Leno’s car collection. Leno refuses to own a Ferrari not because of any particular automotive feature, but because of the arrogance and rudeness of Ferrari dealers. As Leno explains, “This is not an indictment of the car; it’s just that you’re spending a tremendous amount of money. You should be made to feel like a customer’”(qtd. in Tsui).

In his interview with The Drive, Leno appears incredulous that someone of his celebrity and status is treated in such a disrespectful manner by dealership personnel. As a white and [extremely] privileged male, Leno has most likely never had to deal with offensive and patronizing automotive dealers and service representatives. Although Leno is now recognized as someone extremely knowledgeable about cars, I suspect that due to his race and gender, he has been treated as a car savvy individual for most of his driving life. Therefore I find it interesting, and somewhat amusing, that Leno finds poor treatment at car dealership unconventional and surprising, particularly since rude and insolent behavior at car dealerships has been – and continues to be – an all too common experience among women drivers.

In 2014 – in an examination of women’s online car advice sites – I discussed women’s common experience at automotive dealerships, drawing particular attention to how it contrasted to that of men. As I wrote:

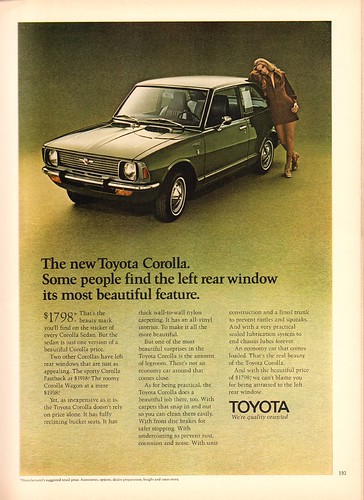

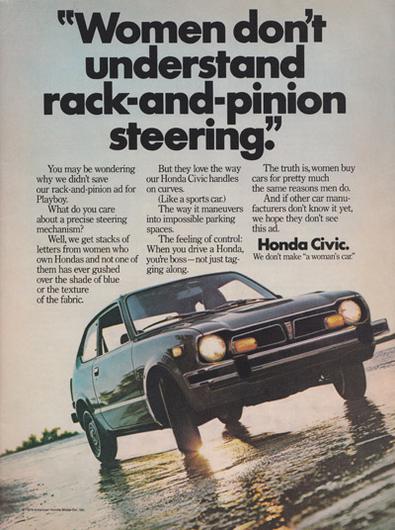

To the majority of car-owning women, visiting an automotive dealership or service establishment is an unpleasant, unnerving, and frustrating experience. When seeking to purchase or service an automobile, women are often subject to sexist, dismissive, and patronizing behavior from automotive personnel. Women must often tolerate unwanted invitations or inappropriate comments regarding their appearance or sexuality, are withheld crucial information due to an assumed lack of basic car buying knowledge, and are ignored or dismissed when accompanied by a male companion. Although women influence nearly 85 percent of new car sales (Muley), the experience of women at automotive dealerships differs significantly from that of male drivers. Not only are women subject to inferior treatment, but they also often wind up paying considerably more for a vehicle than a male customer (Ayres). It would seem that such insolent behavior—as detrimental to future car sales—would be discouraged in those who sell and service cars. However, its continued existence suggests it is part of a broader strategy to maintain masculine control of the auto showroom as well as to limit and contest women’s financial and automotive competence.

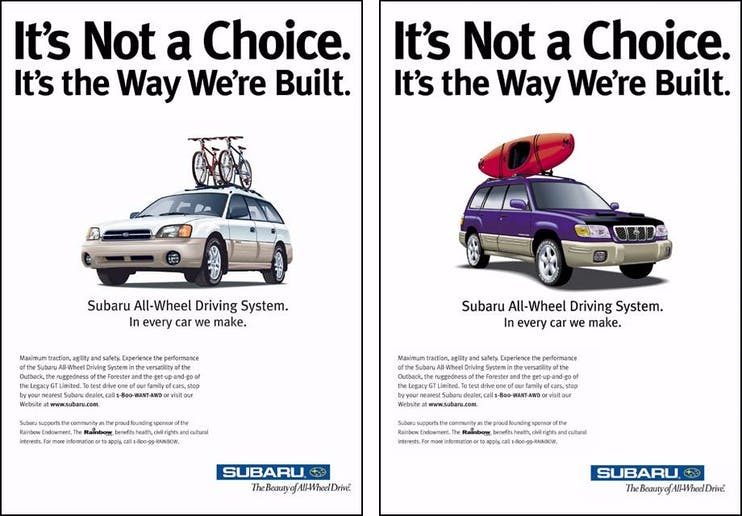

This inferior treatment, as I noted, is based on a number of underlying factors. The first is the longstanding association between automobiles and masculinity. The second is an outdated but ingrained automotive sales technique which has its origins in horse-trading and its tradition of male contestation.

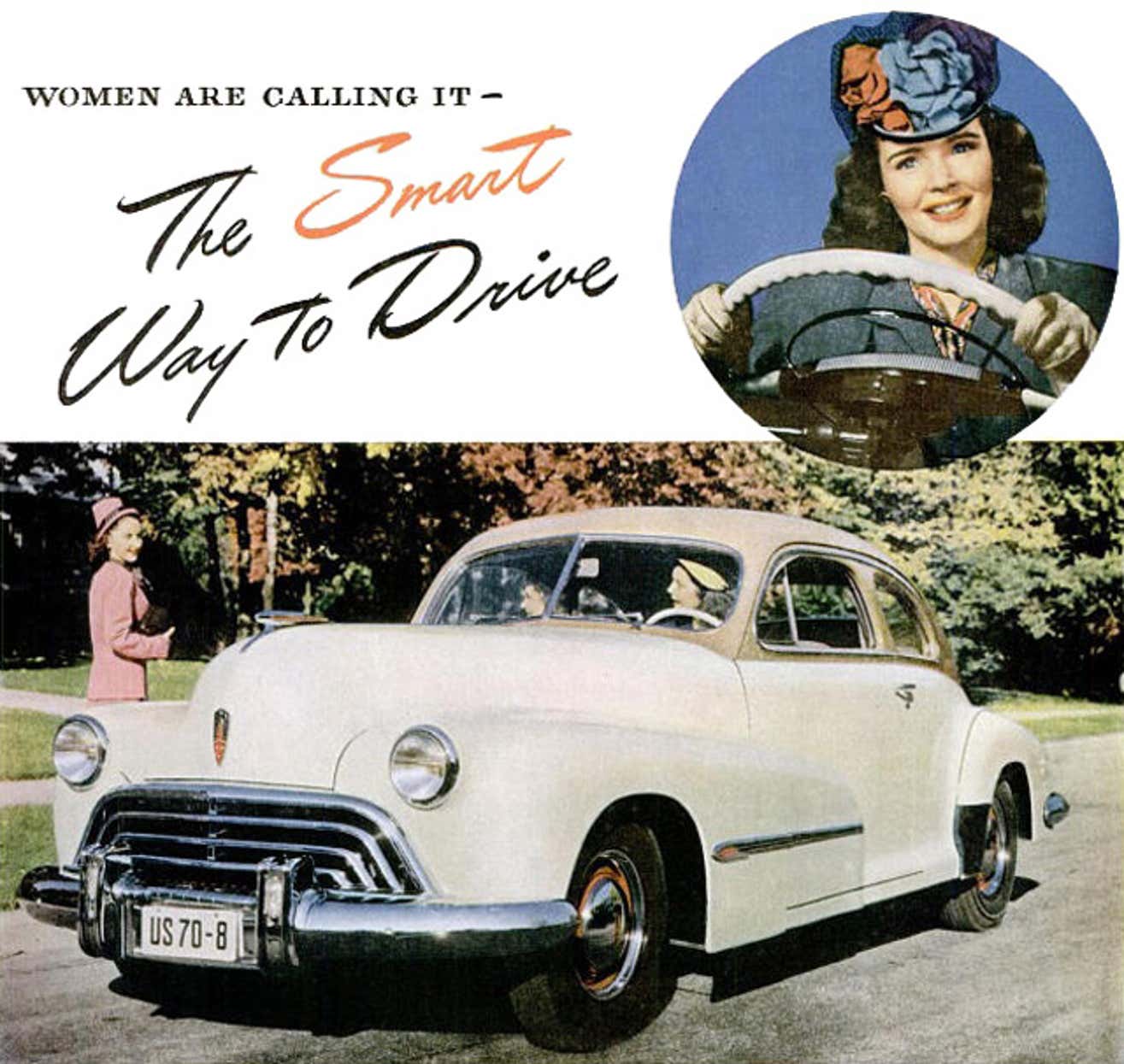

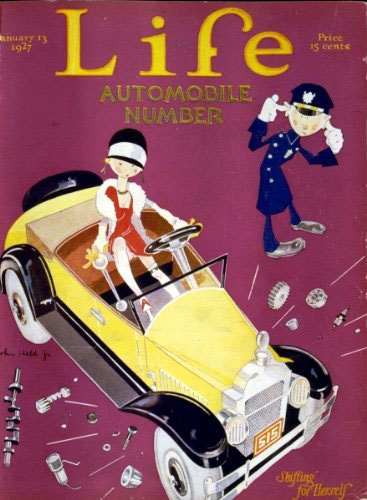

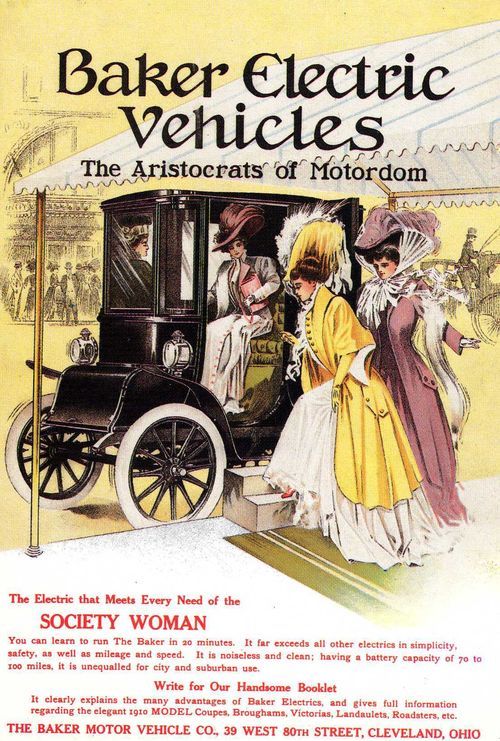

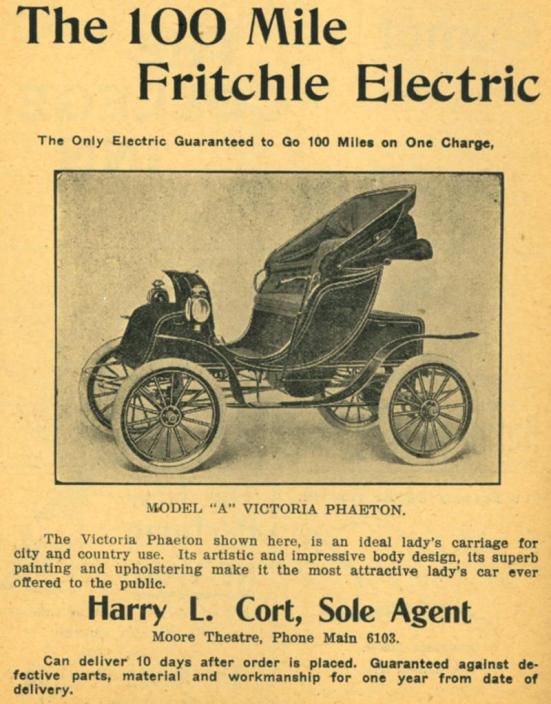

Antiquated notions of masculinity and femininity have traditionally linked technological expertise with the male gender. During the early years of automobility, this association was effectively applied to cars. While early automotive accounts reveal a growing female curiosity in the gasoline-powered automobile, fears over what women might do with a powerful machine created anxiety among male keepers of the status quo. Consequently, attempts were made to stifle women’s interest in automobiles, often through the association of driving ability with physical strength and mechanical expertise, qualities considered lacking in the woman driver. As historian Julie Wosk remarks, “men had long been portrayed as strong and technically able, women as frail and technically incompetent, or at least unsuited to engaging in complex technical operations” (9).

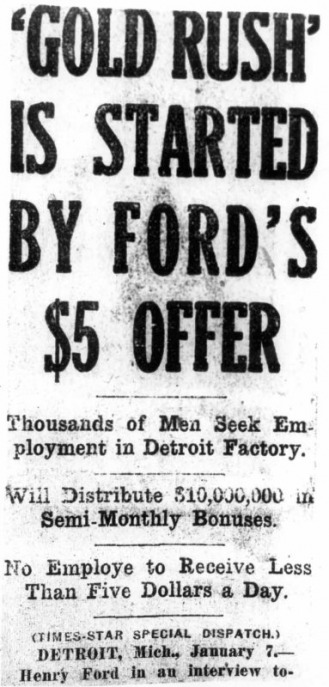

In the years following World War I, industrialization threatened traditional sources of male identity. The physical strength and mechanical ability necessary for the operation and maintenance of automobiles provided a means by which men could reassert themselves as masculine. Linking automobile use to technical expertise established men as more authentic drivers and initiated the longstanding association of the automobile with masculinity. As Clay McShane notes, “when men claimed mechanical ability as a gender trait, implicitly they excluded women from automobility” (156).

The association between masculinity and automotive technology was exacerbated in the years following World War II. Male teens often engaged in hot rod or muscle car culture as a means to further their automotive education and construct themselves as masculine. Aligning masculinity with cars, mechanical proficiency, and risky driving placed young women on the margins of teenage car culture, as either passengers or “avid spectators” (Genat 47). The exclusion of women from these sites of automotive education and practice assured that automotive knowledge would remain in men’s hands. It could be argued that the computerization of the automobile in the twenty-first century has leveled the playing field, as mechanical ability is no longer a prerequisite for servicing automobiles. Yet despite the fact that auto repair personnel are more likely to be diagnosticians than mechanics, the association of technological expertise and masculinity stubbornly remains. Women often feel compelled to bring men along with them to the dealership when purchasing or servicing an automobile, not because a man is inherently more car savvy, but because his maleness is considered unquestioned evidence of automotive knowledge.

Horse-trading and its tradition of male contestation were incorporated into the bicycle and automotive trades that followed. As women were seldom actors in the horse-trading arena, they were unfamiliar with commonplace bartering methods and uncomfortable in the hyper-masculine environment in which such tactics were practiced. While women, in the twentieth century, were increasingly cast in the role of consumer, their experience as buyers was limited to that of one-price retailing. Consequently, most women were totally unequipped to participate in a car buying process that relied on aggressive bartering. Women’s discomfort was intensified by the misogynist atmosphere of the showroom, in which the negotiation process was often framed in the violent language of physical and sexual conquest. Salesmen often called upon such rhetoric to take advantage of the female car buyer, believing that keeping women drivers less informed and more easily intimidated was an effective means to guarantee higher profit margins. While the women’s movement of the 1970s, and the subsequent growth of women in the workforce, may have increased the auto industry’s awareness of women as a distinct and profitable market segment, as Gelber notes, “the message often failed to percolate down to the showroom floor” (158). Although in the twenty-first century, women make up nearly half of automobile consumers (Bird), a lack of automotive knowledge and uneasiness with negotiating techniques ensures they will be treated in much the same manner as their horse-buying counterparts of a hundred years past.

Women have become increasingly car savvy since this article was written, due in part to vigorous automotive research as well as participation on online automotive sites and forums. The rise of women in the auto industry, including an increase in the number of female auto dealers, has also somewhat weakened the association of cars and masculinity, resulting in a more comfortable and less confrontational car buying experience. But there is little doubt that bad behavior against female automotive consumers remains. Therefore, while Leno may be admired for his stance against Ferrari dealerships, he should understand that he is by no means alone. For women have been treated with disrespect not only by fancy luxury car dealers, but by salespeople of all makes and models of cars since the first Model T drove off the car lot over 100 years ago.

Note: portions of this blog are excerpted from “Women Auto Know: Automotive Knowledge, Auto Activism, and Women’s Online Car Advice”.

Ayres, Ian. “Fair Driving: Gender and Race Discrimination in Retail Car Negotiations.” Harvard Law Review 104, 4 (1991): 817–872.

Bird, Colin. “Women Buying More Cars, Favor Imports.” Cars.com 31 Mar 2011.

Gelber, Steven M. Horse Trading in the Age of Cars: Men in the Marketplace. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Genat, Robert. Woodward Avenue: Cruising the Legendary Strip. North Branch, MN: CarTech., 2010.

Lezotte, Chris. “Women Auto Know: Automotive Knowledge, Auto Activism, and Women’s Online Car Advice.” Feminist Media Studies (2014 ): 1-17.

McShane, Clay. Down the Asphalt Path: The Automobile and the American City. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Muley, Miriam. “Growing the 85% Niche: Women and Women of Color.” AskPatty.com. 2008.

Tsui, Chris. “Jay Leno Won’t Buy a Ferrari Because He Hates the Dealerships.” TheDrive.com 4 Feb 2022.

Wosk, Julie. Women and the Machine: Representations from the Spinning Wheel to the Electronic Age. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003..