This is an editorial written while a graduate student for a journalism class in 2009, a low point in the American auto industry. It has been somewhat updated with subsequent research, but most of the original points remain and have continued relevance today.

American auto manufacturers have never quite figured out the female car buyer. Certainly domestic car companies recognize women’s value as consumers. After all, women purchase over half the automobiles sold in the USA each year. Yet while Ford, GM and Chrysler rely on women to buy cars, they have never developed an appreciation for women as drivers. Year after year, American auto companies attempt to appeal to women’s practicality, frugality and rationality by offering them vehicles that are safe, efficient, functional and just plain boring. The female driver, in the minds of the US car manufacturer, only desires a car that will aid in the performance of her domestic role as caretaker and consumer. The notion that a woman might desire a vehicle that is small, nimble, sporty and reliable, as well as fun to drive, is rarely a consideration. Thus the woman who desires more from a car than functionality, who enjoys the driving experience as much as the car that provides it, must often turn to imports to meet her automotive needs. While it may be an overstatement to suggest that the bleak state of the US auto industry is due to its historical dismissal of women’s driving interests, there remains enough evidence to suggest that the failure of domestic auto manufacturers to build a car that appeals to women is a contributor to the industry downslide.

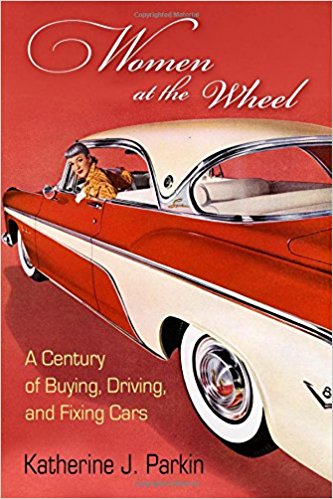

The relationship between US automakers and women has been problematic from the start. There can be little argument that the American automotive industry is a very masculine culture. In the minds of many auto execs, therefore, attention to women’s automobile preferences not only leads to the devaluation of a particular car, but also of the industry that produces it. In order to keep women as customers without alienating male drivers, US auto companies have traditionally called upon a strategy that affirms women’s culturally approved gender role without disrupting the masculinity associated with the automobile. Cars deemed appropriate for women are reconfigured as a form of domestic technology, tools that enable women to fulfill the prescribed role of wife, mother, consumer and caretaker. This approach provides automakers with the opportunity to market functional and practical vehicles – the wagon, hatchback and ubiquitous minivan – as “women’s” cars, while positioning big trucks, sports cars and performance automobiles as suitable for men. And perhaps more important, it allows the community of conservative male auto executives to take an active part in reinforcing traditional gender roles in which all women are moms, and where men have all the fun.

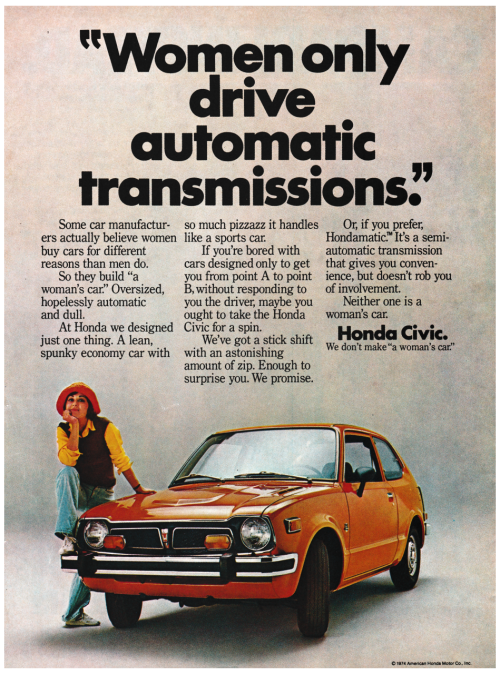

It didn’t take long for women to stop buying into the monolithic US auto industry philosophy. In the post World War II years, home alone in the suburbs, women drove the big cars men purchased for them, often bolstered by cushions in order to reach the accelerator. When women entered the workforce en force during the 1960s, however, they began to look for cars that would not only accommodate their smaller stature, but reflect their newly liberated status as well. Dissatisfied with domestic automobile choices – big and expensive, or cheap and spartan – female drivers began to notice that the economical, well-appointed and well-designed Asian and European cars “fit” them better. As they switched to imports, women found the vehicles to be more reliable, durable, and have greater resale value than the domestic cars they left behind. They were also a lot more fun to drive.

When interviewing elderly women about their early automotive experiences a few years ago, I found the switch to Japanese automobiles to be a common theme. While women drove domestic cars in their early driving years, many transferred their allegiance to imports once they no longer felt pressure to buy American. Economy, reliability, comfort for their smaller-than-masculine bodies, and resale values were some of the reasons cited for downsizing to Japanese models.

US car companies were certainly capable of producing similar automobiles. Ford-Europe and GM-Europe had been building small, stylish, fuel-efficient vehicles for the European and Asian markets for years. Yet US automakers refrained from producing such cars for domestic use. Rather, they continued to build the big, powerful and gas guzzling automobiles, convincing themselves that they could make more money building big cars than small ones. As the self-proclaimed “big boys” of the car world, US automakers remained convinced of their invulnerability to foreign competitors. And as they repeated the mantra “bigger is better,” domestic carmakers failed to consider that the diminutive half of the US population not only might prefer a smaller car, but now had the resources to purchase one as well.

Arrogance, and the fear of becoming “feminized” prevented automakers from considering the needs of the increasingly diverse car-buying public. Cloistered with individuals very much like themselves, Detroit auto men became incapable of viewing the car industry through eyes other than their own. While American automakers continued to build one standardized product in the largest possible volume, import manufacturers considered the divergent needs, driving styles and economic means of its potential buyers, and produced cars accordingly. European and Asian car manufacturers worked hard to appeal to a wide variety of drivers, which of course, included women. US auto manufacturers, on the other hand, told consumers what to buy based on their own monolithic vision. Detroit automakers continued to profess they knew what women wanted without bothering to ask them.

In the past fifty years, the American car buying public has slowly but emphatically switched its allegiance to imports. New studies reveal that members of Generation Y, those between 24-39 years of age, prefer Japanese and European brands to their American counterparts. Young women fresh out of school often start with an inexpensive import, get a minivan during their child-rearing years, then switch to a small, sporty and “fun to drive” vehicle when the kids leave home. While the US automakers may have these women for a few years, they invariably lose them coming and going. In fact, in a recent article published by CBS news, 9 of the 10 top automotive brands for women are imports.

Could women have saved the US auto industry? On their own, certainly not. Robust sales of full size pickups – overwhelmingly purchased by men – have historically kept US auto manufacturers afloat. But female drivers represent an enormous segment of the automobile market uniformly patronized if not ignored by domestic car manufacturers for a very long time. The monolithic vision of the US auto industry, coupled with a cultural outlook based on arrogance and sexism, allowed foreign competition to lure female drivers away when US automakers simply weren’t looking.