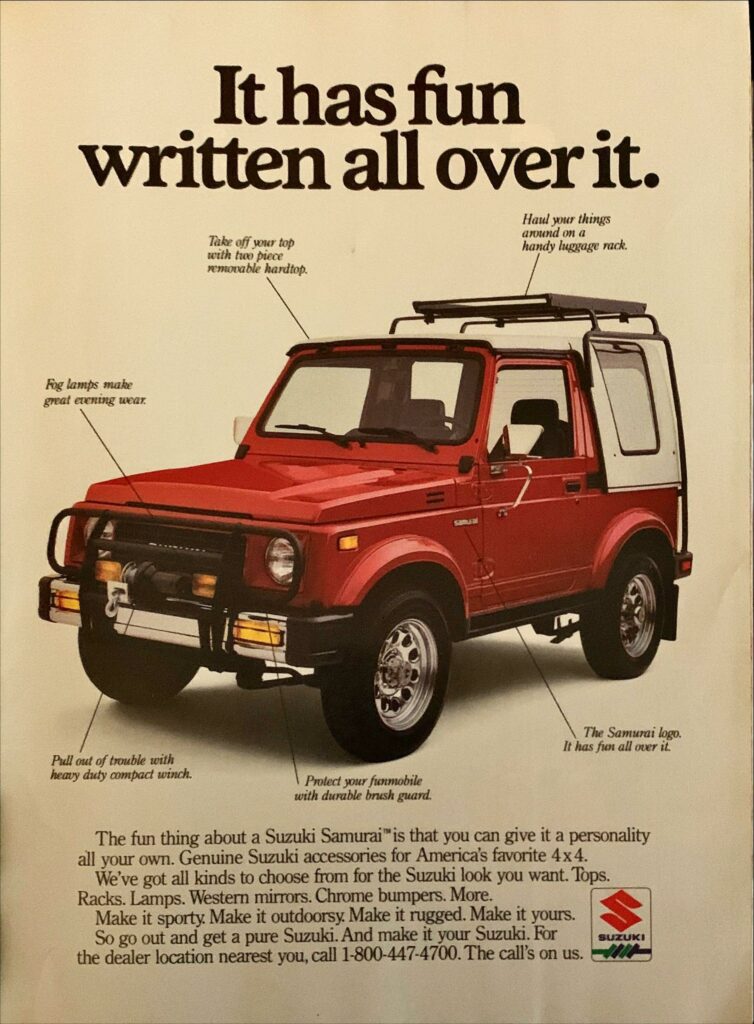

A recent posting on Curbside Classic featured a 1988 Suzuki Samurai advertisement with the quizzical headline: ‘What Young Urban Women Aspired to in 1988?’ The ad features a 30-something woman behind the wheel of the aforementioned vehicle accompanied by a female companion. The women are looking happily out of their respective windows while driving down a charming urban thoroughfare. Without much copy to ponder, the posting was open to comments from interested CC readers. What is interesting in the responses is how often the readers’ experiences support the unspoken premise of the ad. As one responder noted, ‘my mom had one of these. […] there was something about that vehicle that truly appealed to her. Part of it was the size. After 16 years of pretty much exclusively driving the fuselage Chrysler wagon, I think getting back into something small really had its appeal to her.’ Another remarked, ‘I couldn’t understand why she wanted a car that didn’t have a real back seat, which made doing things like picking me up at the airport or carrying anything substantial pretty much out of the question. Now I think maybe that was the whole point for her.’

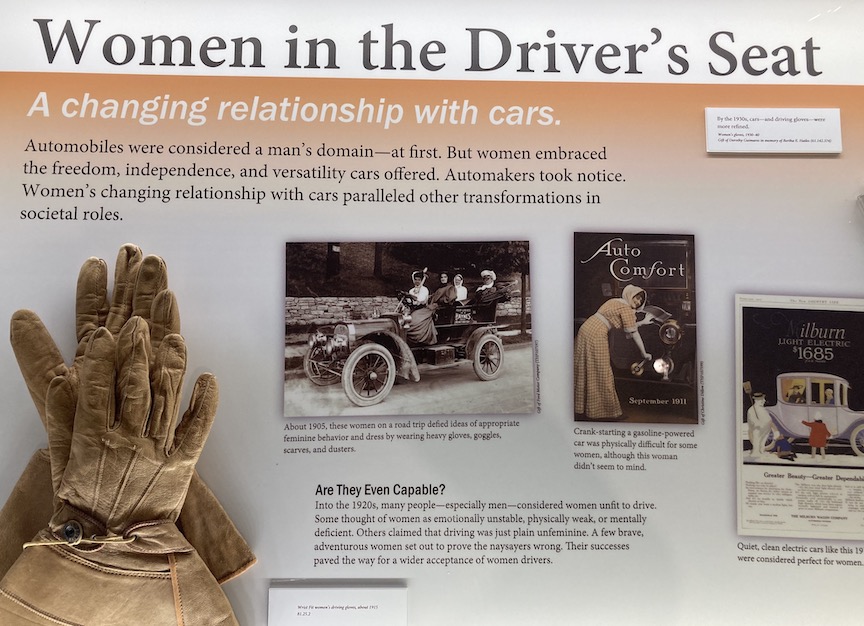

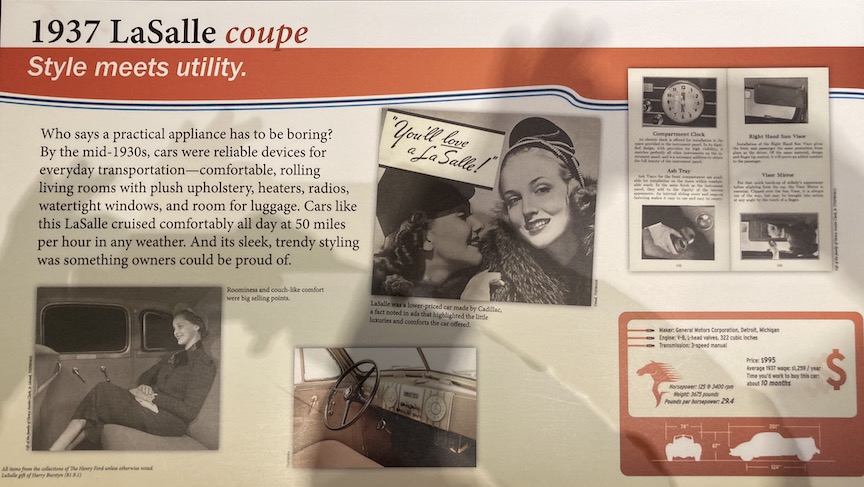

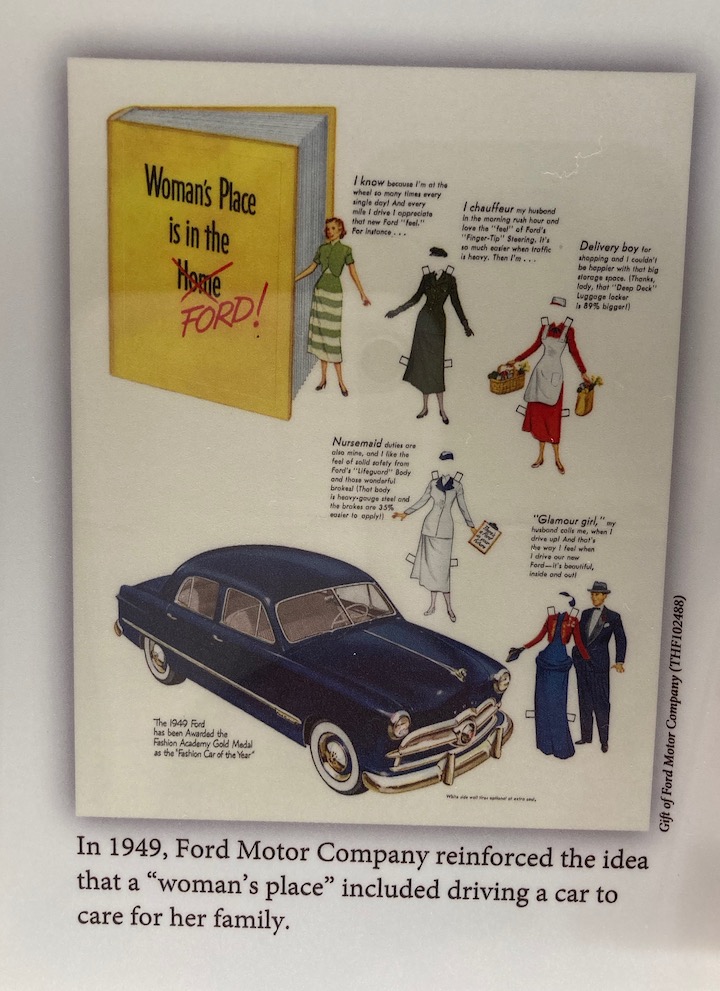

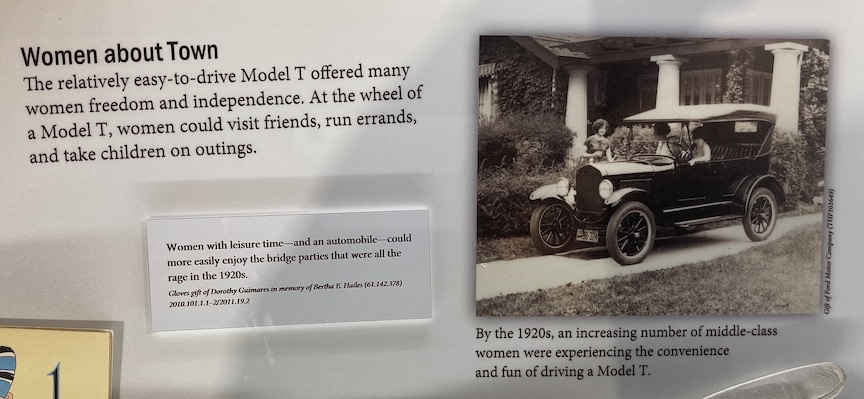

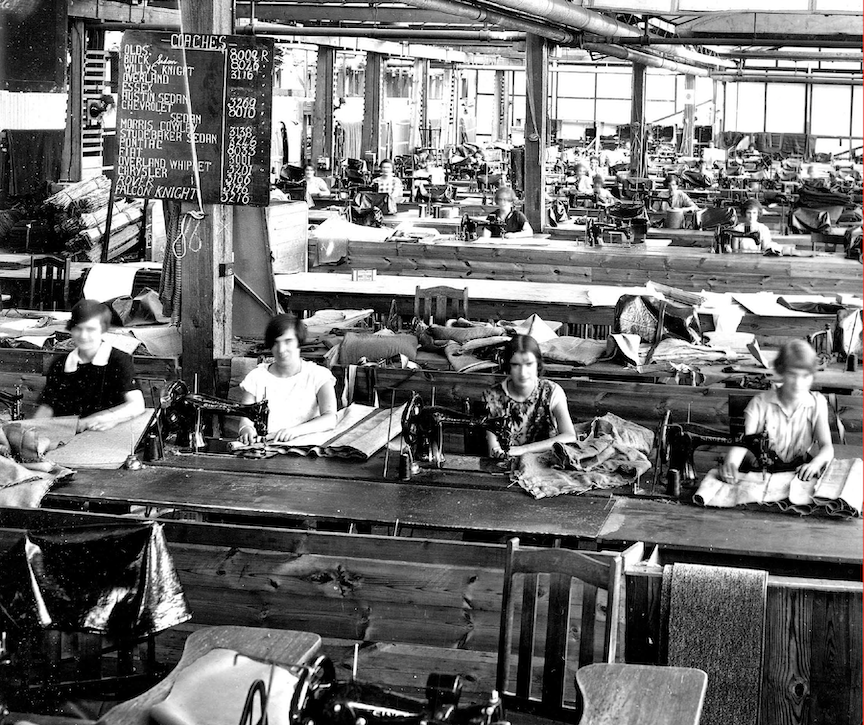

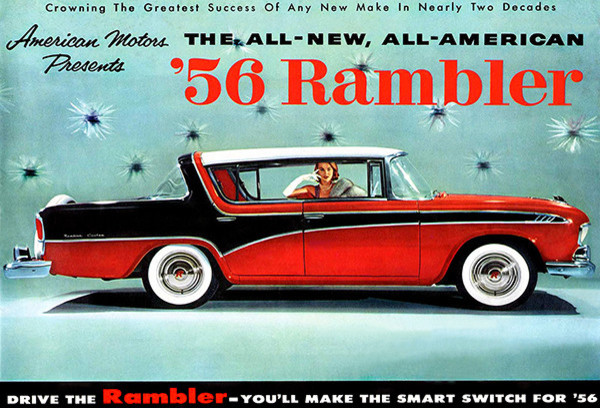

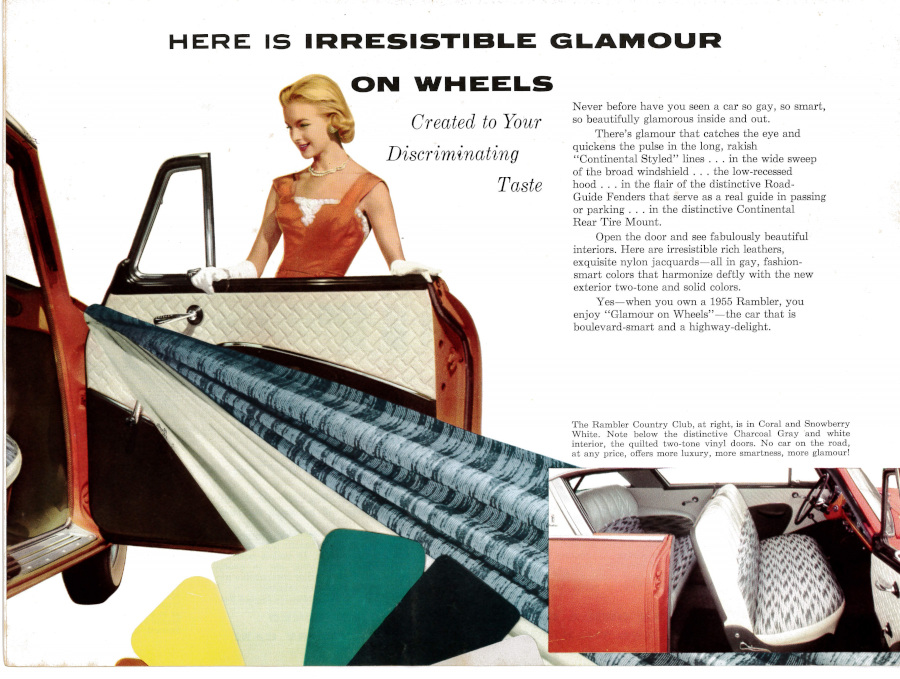

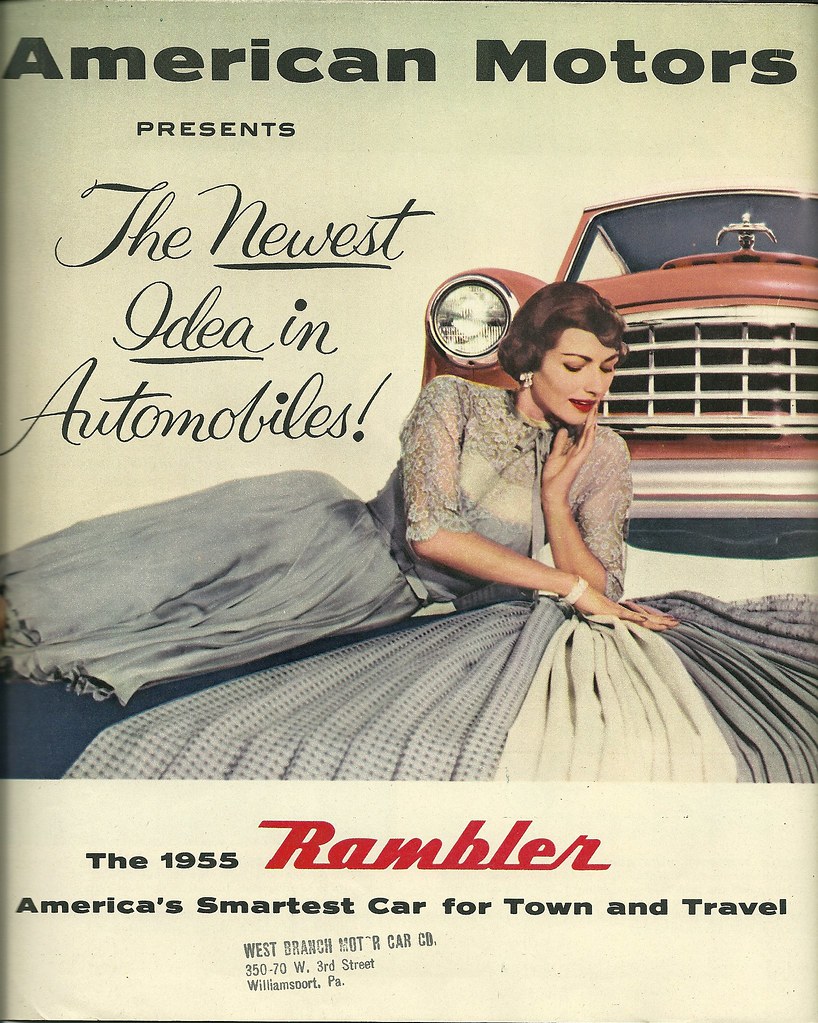

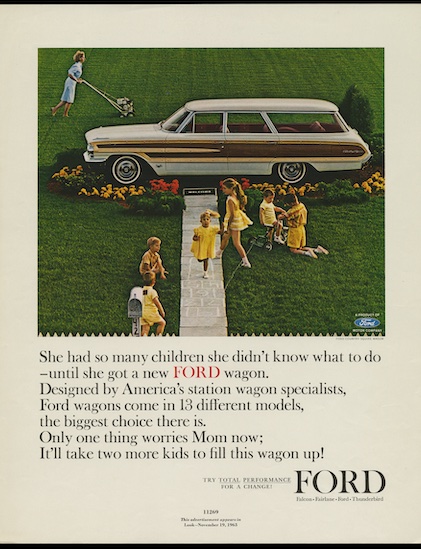

In order to understand the significance of this advertisement, and the comments it generated, it helps to revisit the automotive advertising to women that preceded it. After World War II, when women were expected to leave their wartime factory jobs to create comfortable lives for husbands in the suburbs, marketing to the female consumer was focused primarily on suitable ‘family’ vehicles. In the 1950s and early 1960s, this mode of transportation was the station wagon. Advertising for these automobiles often featured idyllic scenes of mother and [many] children engaging in dad-less family activities around the car, as well as busy mothers with growing families for whom roominess in a vehicle was an obvious necessity.

In the 1960s and early 70s, the station wagon was replaced by the hatchback, which was, as one advertiser claimed, ‘the car designed around a shopping bag.’ In the mid 1980s the world was introduced to the minivan, which as the perfect vehicle for carrying kids and cargo, was unofficially dubbed the ‘soccer mom’ car. Minivan advertising featured moms with kids and groceries and bikes and sporting equipment, all which reinforced the association of family vehicles with the woman behind the wheel.

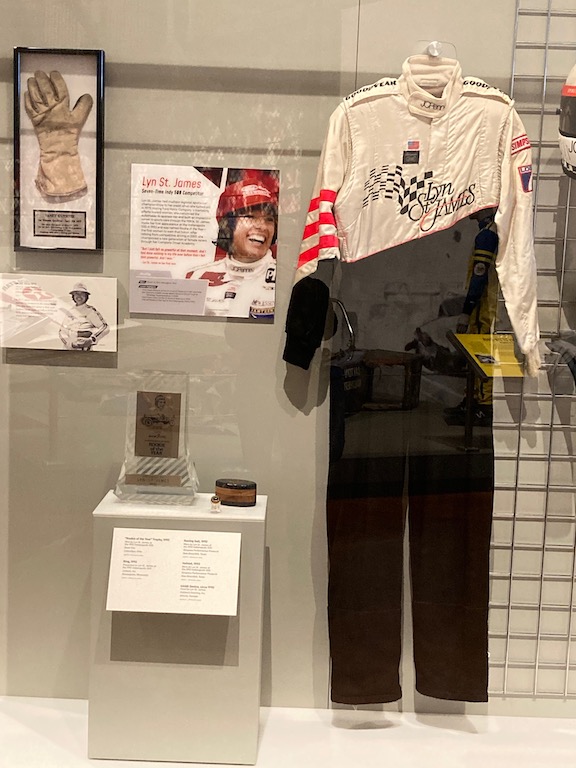

Yet before the minivan morphed into the ubiquitous SUV, a few automotive advertisers – primarily of import vehicles – suggested [gasp!] that the female consumer could be someone other than a mom. The late 1980s/early 90s Subaru campaign reflected this sentiment. As the commenters noted, the Samurai lacked a back seat, which meant there was no room for kids. And its sporty appearance suggested the possibility of adventure outside of playdates, t-ball games, and the banality of suburban neighborhoods. While the women pictured in family car advertising appear content, those in the Suzuki campaign seem downright ecstatic. Other ads in the campaign emphasize the vehicle’s ‘fun-ness’ and remark on its multiple identities as sporty, outdoorsy, and rugged. As the polar opposite of the ‘mom’ car, Suzuki advertising promised an exciting, adventurous, and well-deserved getaway for married and single women alike. Noted a Curbside Classic commenter, ‘I had a female co-worker who had a Samurai – it served as both her nice day-in-the-summer and her winter weather car. Interesting little fleet for a woman in her 20s.’