Last summer, female racing icon Danica Patrick once again made the news. However, it was not for her achievements behind the wheel, but rather for a comment she made while being interviewed on a broadcast designed with younger viewers in mind. When asked by a young admirer when the world would see a woman racing in F1, Patrick dismissed the whole notion, arguing that the ‘female mind’ would prevent women from such a motorsport achievement. Jalopnik writer Elizabeth Blackstock was highly critical of the former racer; as she argued, ‘a sporting broadcast designed for young children is perhaps not the best venue to share a deeply discouraging message to a large subset of young viewers.’ Social media platforms were flooded with negative responses from motorsport fans; as an X poster exclaimed, “There’s nothing worse than when a woman gets a platform in a male dominated space and uses it to showcase herself as the “exception” instead of using it to deconstruct harmful stereotypes.’ As one who has broken considerable barriers in the racing world, Patrick has the props and the potential to serve as a role model for young female aspiring racers. However, Patrick’s comment suggests she has little interest in assuming that role.

The reluctance of a groundbreaking female pioneer in any male-dominated profession to serve as a role model is not without precedent, nor is it particularly uncommon. Dr. Shawn Andrews, writing for Forbes, notes there are a number of reasons why women in power do not support or encourage other women. Andrews discusses phenomena such as the ‘Queen Bee Syndrome,’ when women display behavior more typical of men to display toughness, set themselves apart from lower ranking women, and fit in. Andrews also notes that when competition for ‘spots’ in favored in-groups increases, ‘women are less inclined to bring other women along.’ However, that which perhaps applies most directly to Patrick is the notion that, due to the obstacles women – particularly those first to attain success in predominately male fields – face in their career, their attitude toward other women is often ‘I figured it out; you should, too.’ I found this to be a somewhat common practice in my past career in advertising, where women who had struggled to attain respected positions were sometimes reluctant to mentor younger up-and-comers, endeavoring to keep hard-earned power and prestige for themselves.

Much has been written about the importance of female representation in male dominated areas in both academia and the media. In a study of the choice of college majors, Porter and Serra argue that the lack of women in traditionally male fields may be attributed to the scarce number of female role models. As they write, ‘due to historical gender imbalances, it is difficult for young women to come into direct contact with successful women who have majored in male dominated fields and can inspire them to do the same’ (1). Drury et al argue that female role models in STEM fields are, in fact, effective in combating ‘stereotype threat’; i.e. negative stereotypes that cast doubt on a woman’s ability to perform. Although Mary Barra encountered incredible obstacles within the historically masculine auto industry to become its first female CEO, she remains ‘a strong advocate for encouraging more women to pursue careers in traditionally male-dominated fields’ (Standley). Perhaps the most vocal promoter of female role models is former Secretary of State Madeline Albright, who famously stated, ‘there’s a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other.’

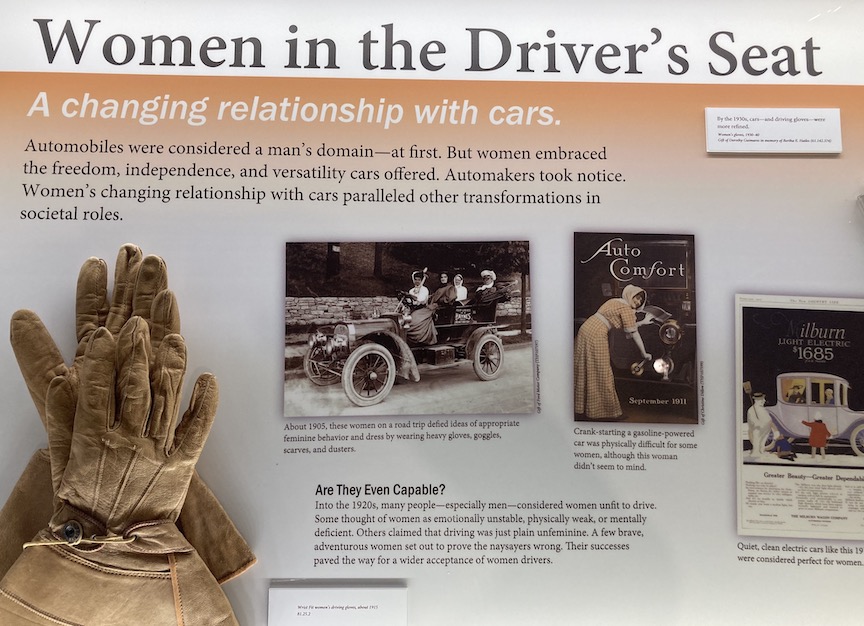

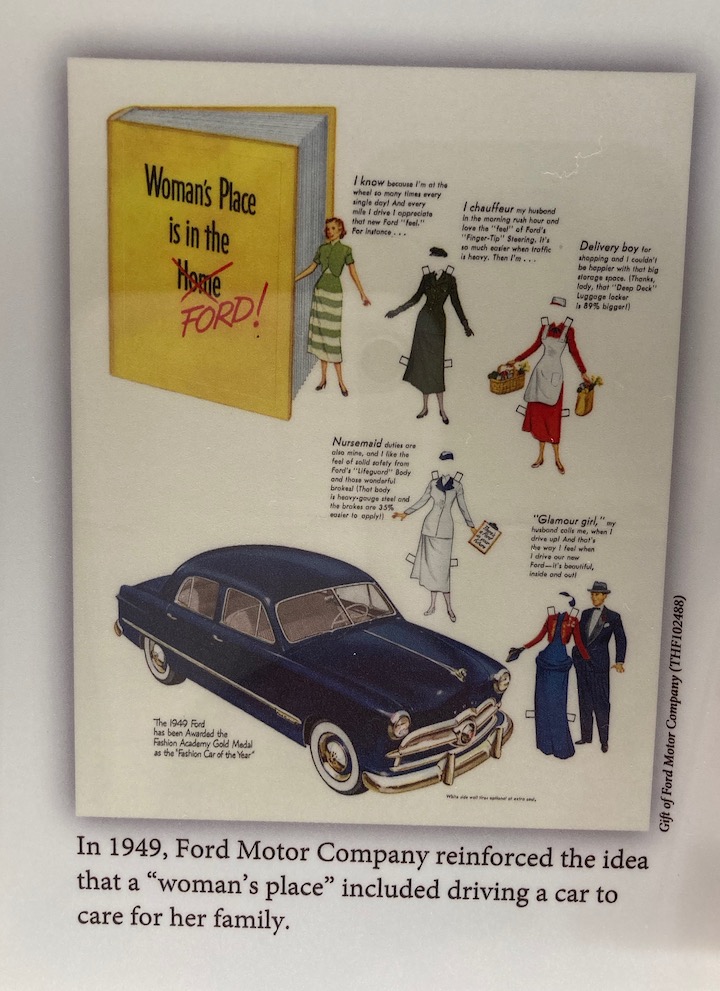

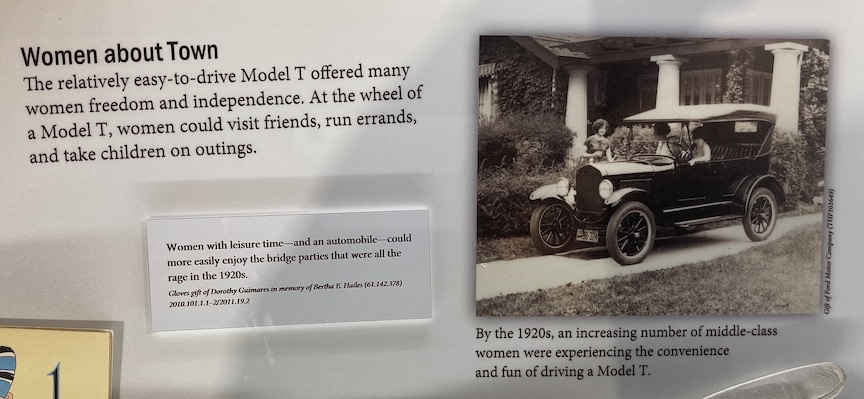

Throughout most of its long and storied history, motorsport has been unwelcoming to women. Although motorsport is one of the few competitive sporting activities in which men and women are allowed to engage on equal footing, females are vastly underrepresented in the majority of motorsport arenas. In the United States, women comprise over 50% of licensed drivers. Yet while there is no current data on the percentage of female motorsport participation, it is estimated that women’s involvement in combined motorsport venues is less than 4%. Barriers to women’s inclusion are both numerous and complicated. Obstacles include societal factors; young girls are discouraged from engaging with ‘toys that move’ and are less likely to be introduced to motorsport at a young age than their male peers. Longstanding systemic discrimination and harassment within racing organizations and masculine motorsport cultures is also a factor. As Shackleford writes, “the rules that create race events celebrate and encourage an exclusively masculine, distinctly stratified, labor-intensive relationship between man and machine” (230).

“More Than Equal” – a major study on female participation in motorsport – argues that while costs, inappropriate culture, and negative stereotyping of skill and ability are major barriers to women in motor racing, a significant contributor is the lack of female role models and mentors in the field. Without female representation in all levels of motorsport, the activity is off the radar for young women; they are often unaware of motor racing as something in which they can participate. Female representation in a male dominated profession such as motorsport allows girls to imagine that success is possible; when someone who looks like you breaks psychological and physical barriers it is easier to envision that you can, too.

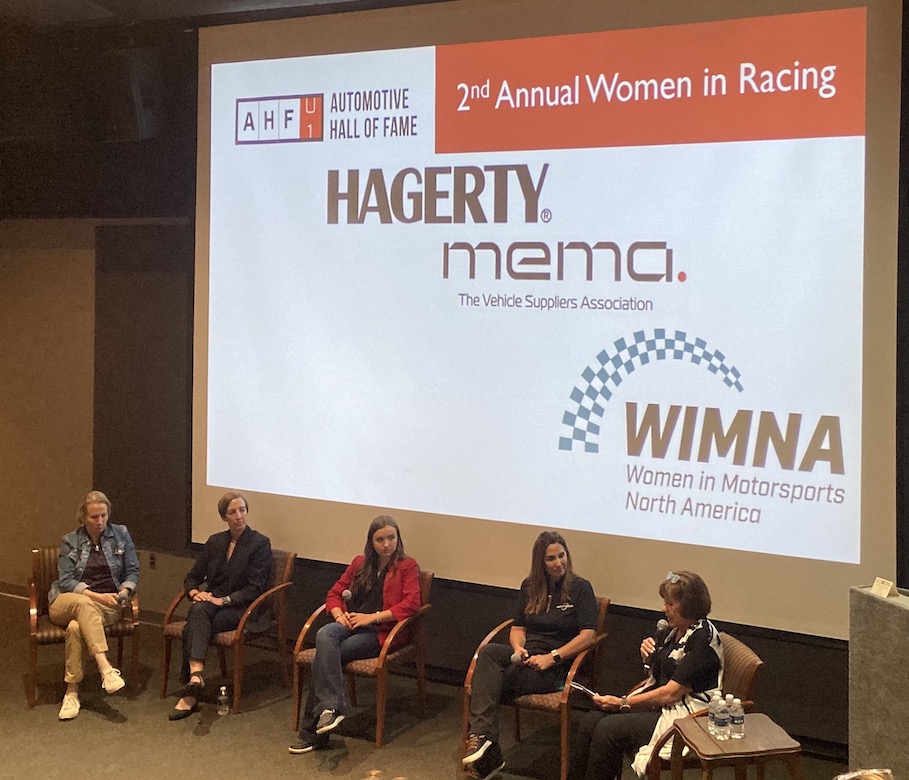

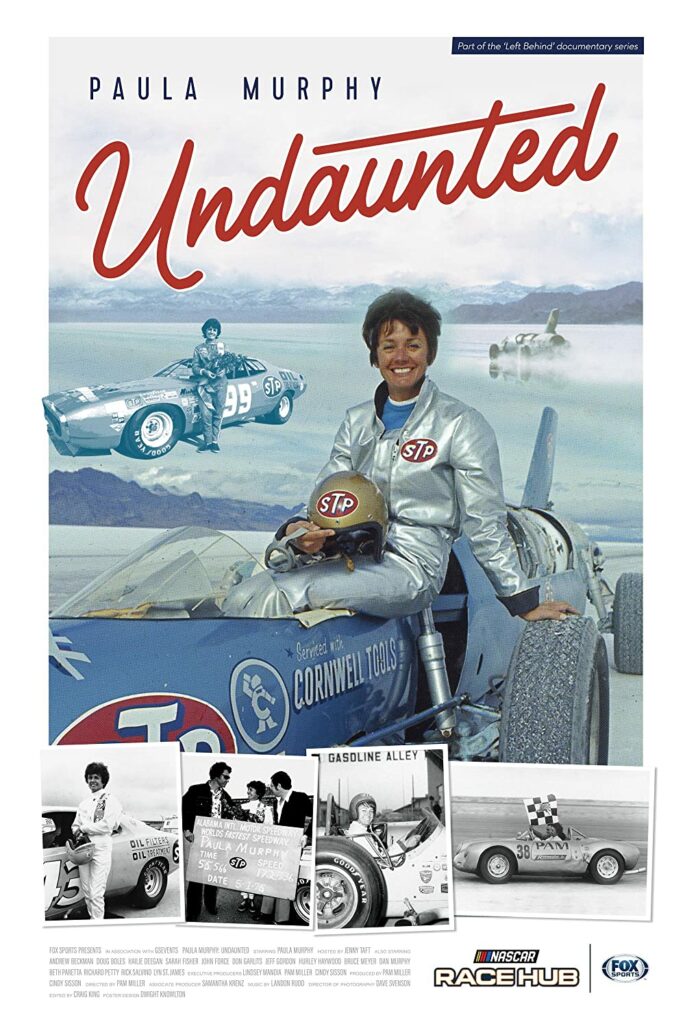

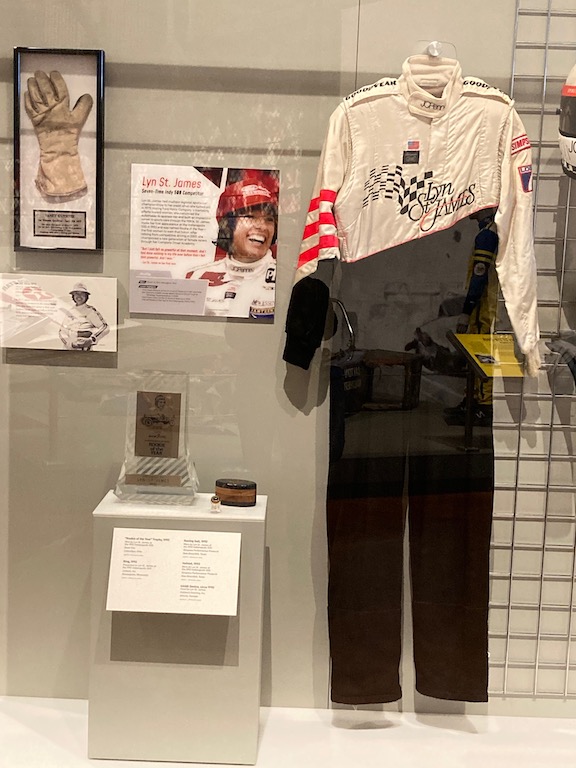

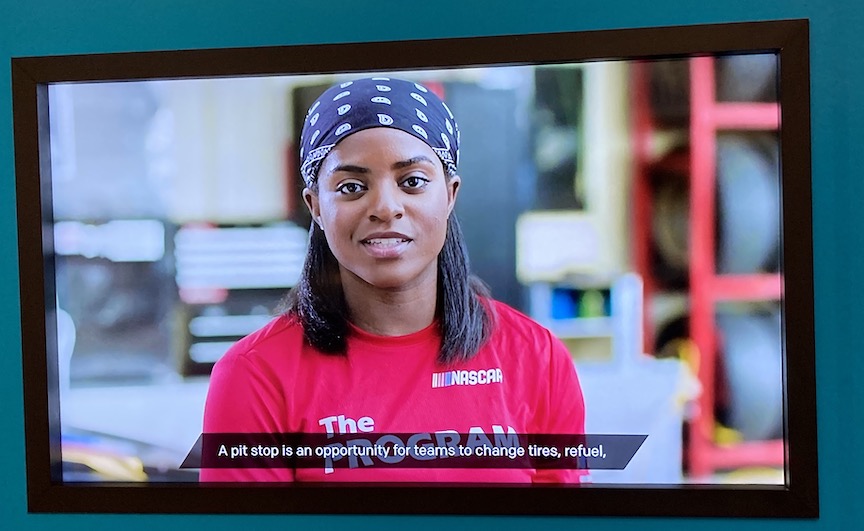

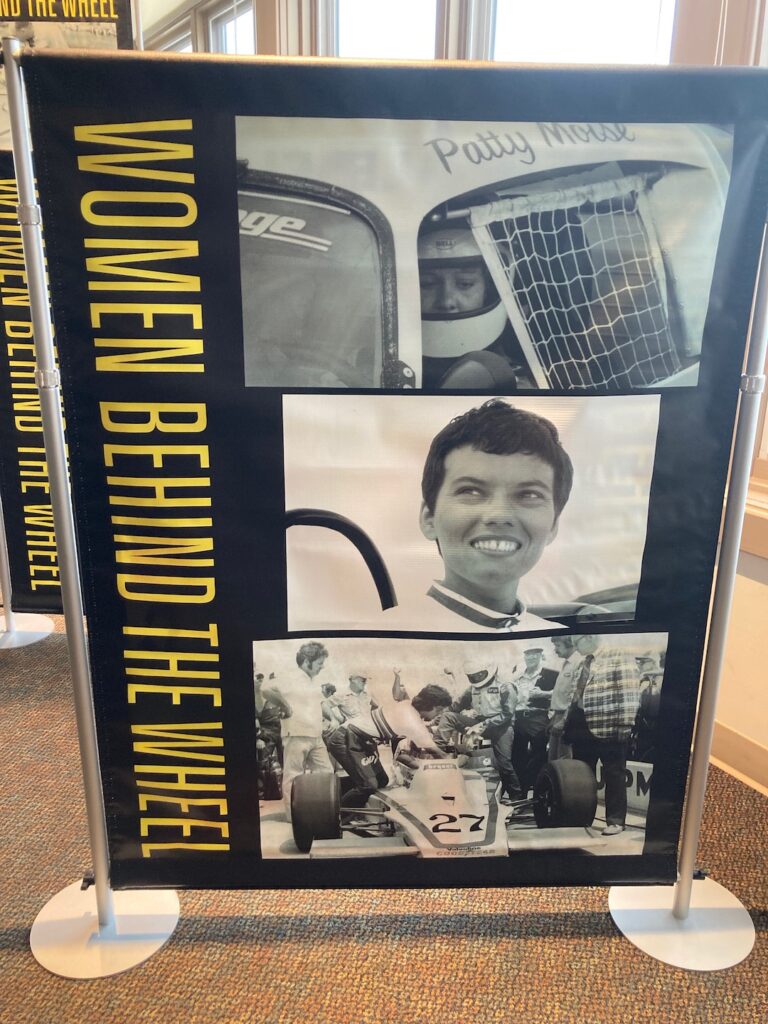

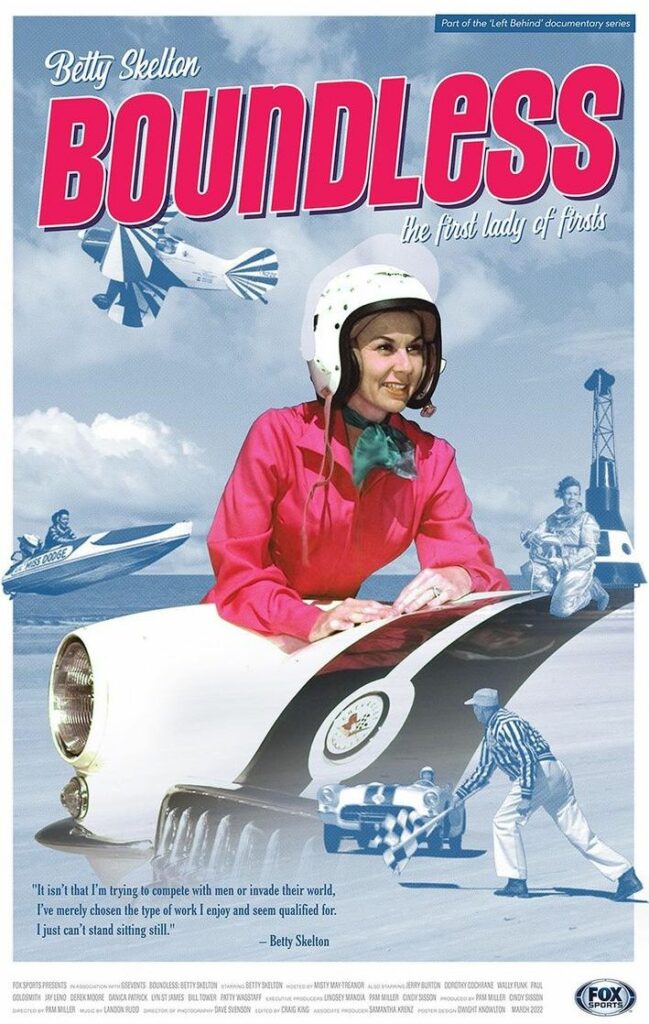

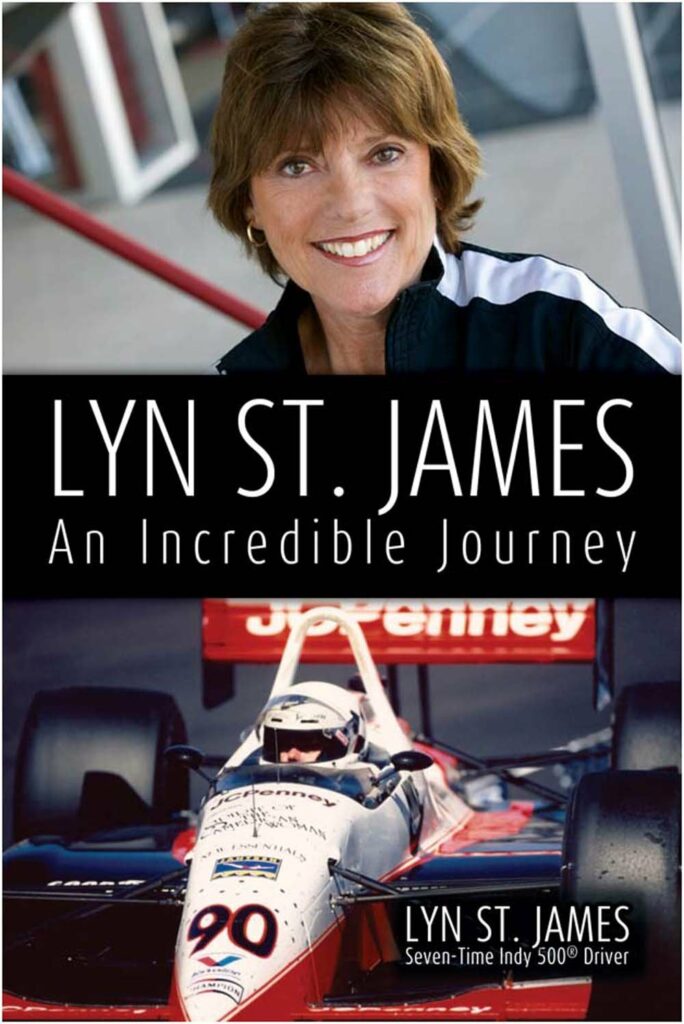

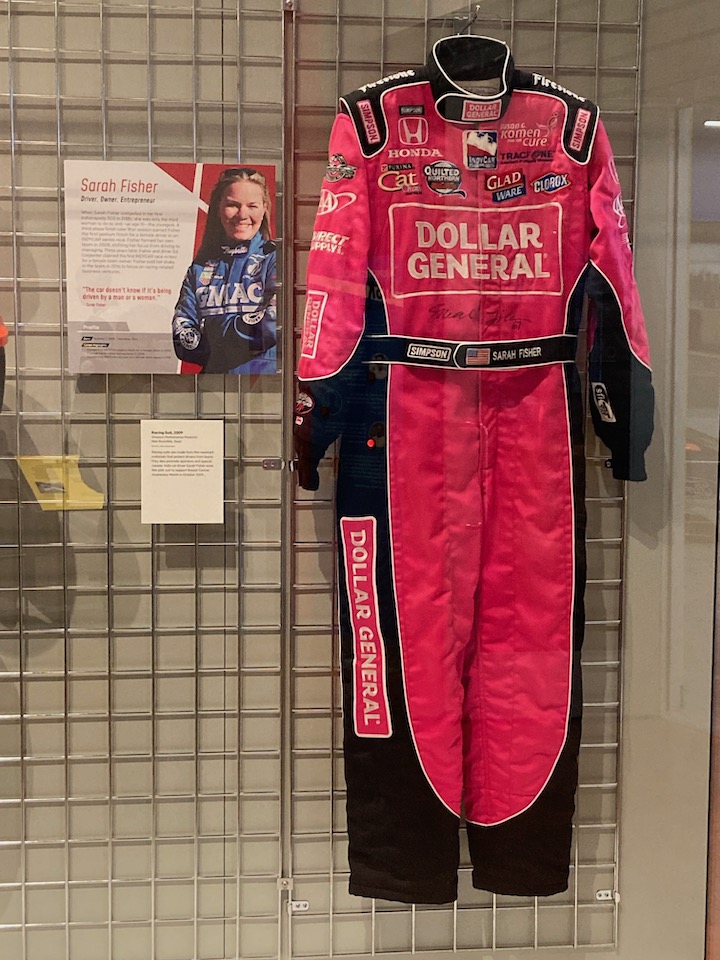

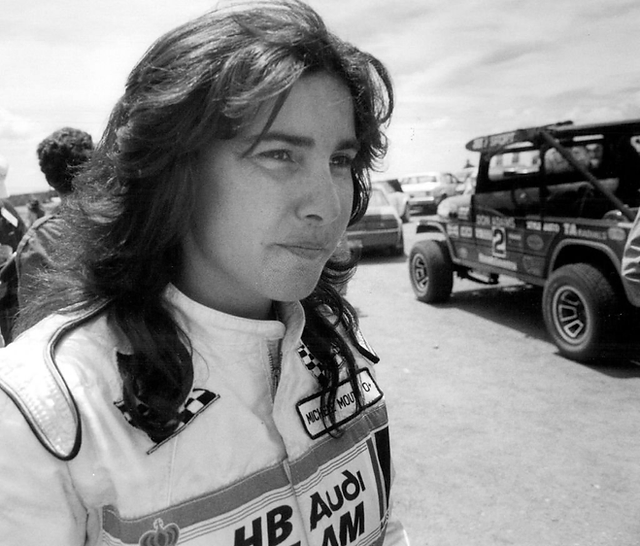

Women who participate in motorsport often express admiration and appreciation for those who have paved the way. In my own research into autocross, for example, women are often encouraged by the large number of female autocrossers who have not only succeeded, but are willing to teach and mentor those new to the sport. Female racing series including the W Series have provided a platform not only for those who participate, but also for those who aspire to one day join them on the track. Retired racers – including Indy 500 Rookie of the Year winner Lyn St James and French rally driver Michele Mouton – have created organizations specifically for the development and promotion of women in motorsport. Automotive organizations, museums, and institutions that feature and promote female racers in displays and special exhibitions – including the Automotive Hall of Fame and the Henry Ford – provide young visitors with exposure to female groundbreakers and role models.

It is unfortunate that Danica Patrick – perhaps the most visible and successful woman in the contemporary racing world – has chosen to discourage young girls from participating in motorsport by framing herself as the ‘extraordinary exception’ rather than a role model to which others may aspire. Hopefully the next female racing phenomenon – and there are a few up and coming superstars – will use their platform to encourage and promote women in racing. The future of women in motorsport depends on it.

Albright, Madeleine. “Madeleine Albright: My Undiplomatic Moment.” nytimes.com 12 Feb 2016.

Andrews, Shawn. “Why Women Don’t Always Support Other Women.” Forbes.com 21 Jan 2020.

Blackstock, Elizabeth. “Danica Patrick Really Isn’t Helping Women Get Into Motorsport.” Jalopnik.com 15 July 2023.

Drury, Benjamin J., John Oliver Siy, and Sapan Ceryan. “When Do Female Role Models BenefitWomen? The Importance of Differentiating Recruitment From Retention in STEM.” Psychological Inquiry 22 (2011): 265-269 .

Motorsport.com “‘More than Equal’ Publishes Findings from Female Motorsport Study.” 7 July 2023.

Porter, Catherine and Danila Serra. “Gender Differences in the Choice of Major: The Importance of Female Role Models.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12(3) July 2020.

Rosvoglou, Chris. “Fans were Not Happy with Danica Patrick’s Opinion on Female Drivers.” The Spun July 2023.

Shackleford, Ben. ‘Masculinity, Hierarchy, and the Auto Racing Fraternity: ThePit Stop as a Celebration of Social Roles.’ Men and Masculinities 2(2) (1999): 180-196.

Standley, Edward. “Harnessing the Power of Female Buyers: Insights from Mary Barra, CEO of General Motors.” FutureStarr.com 18 August 2023.